President Putin has sent his crack military troops to Syria with a much broader set of objectives in mind than preventing the downfall of President Assad. The Russians have no illusions that they can put an end to the horrific bloodletting in Syria. They know the country well, especially what remains of its army. They have no intentions of taking the risk of sinking into the civil war quagmire, as President Obama predicted they would, because they are not planning on introducing ground troops to the battlefields there.

In fact, Putin has embarked upon a very ambitious endeavor to turn the page on the painful (for him) expulsion of the Soviet Union from Egypt orchestrated by Dr. Henry Kissinger and executed by President Sadat in the early seventies. Since that point, the Kremlin has been relegated to a secondary role – if any – in the region, restricted to maintaining some degree of influence in countries such as Syria, Libya and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. However, Putin feels that the void created by the current US administration in the turbulent Middle East clearly invites him to play his hand. Although he probably can invest only limited resources in his new project, bearing in mind Russia’s severe economic difficulties and the steady decline of its military capabilities, Putin is bent on trying to establish a Russian sponsored new version of the old Baghdad Pact as the core anchor of the emerging Middle East.

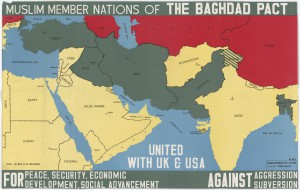

In 1955, Great Britain – still aspiring to exercise dominant influence in its former empire – enlisted Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Iraq and Jordan into what was planned to become a solid alliance that would cement the links between the Middle East and the West. The Baghdad Pact encountered stiff Soviet opposition over the years and was finally dissolved in 1979. Now Putin is seeking to forge a similar alliance, although he is not necessarily interested in a formal treaty, consisting of Iran, Iraq and Syria complemented by increasing separate cooperation between Moscow and General Sisi’s Egypt, which publicly supports the Russian intervention in Syria, and the Kurds, who the Russians are urging to attack ISIL’s de facto capital in Raqqa. The Russian planners have even allocated a role for Israel in their effort to redesign the political landscape: They are offering to buy a substantial chunk of Israel’s newly discovered gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean, largely owned by Noble Energy of Texas, and provide military guarantees against attacks on the offshore installations by Hezbollah, which is already equipped with Russian-made 300 km-range Yakhont surface-to-sea missiles. “Gazpromistan,” as energy experts often refer to Russia, is also proposing to take care of exporting the gas to Europe.

The first move Putin undertook after deploying his front line aircraft to the Bassel Al-Assad air base near Latakia was to offer to expand his air campaign to neighboring Iraq. Whereas in Syria the Russians do not focus on targeting ISIL, they have promised to do so in Iraq and Prime Minister Abadi, disappointed with the American performance so far, is proving receptive. It won’t be long before Putin probes whether the Iraqis would be willing to grant him an airbase in their territory. Tallil Air Base, operated by the Americans until 2011, would be, perhaps, the most likely choice.

Iran is already concluding huge commercial deals with Russia, including for transfer of space technology, and is promised to benefit later on –once sanctions relief takes effect — from expensive arms deals with Russia to modernize its outdated air force and tank fleet. Those in Washington who predicted an era of growing tacit cooperation between the US and Iran following the nuclear deal, mainly in combating ISIL, have to wake up to a reality in which Teheran has chosen closer collaboration with Putin.

Yet the Iranians are also harboring increasing suspicions of Putin’s intentions. They recognize that Moscow is not committed in any way to the longterm preservation of the Assad regime and their priorities in Iraq do not automatically match those of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Assad’s entourage is already expressing concern over Russian references to a possible compromise in Syria and the inauguration of a transitional government. And for their part the Iranians are worried that Putin would prefer at the end of the day to seek an accommodation with whoever arrives next at the White House towards a sort of joint management of the chaotic region. Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, in particular, view the Russians not only as partners (in Syria) but also as competitors for eventual control over the land corridor they dream of establishing between Iran and the Mediterranean coast stretching from the Shiite provinces of Iraq through the Sunni al-Anbar desert province they hope to subdue and on to the Euphrates Valley in Syria and further west.

It goes without saying that Putin is also motivated by the fear of instability amongst the large Muslim communities of the Upper Volga and the Caucasus. He is also concerned about the significant penetration of ISIL into the central Asian Muslim republics. He knows what Obama tends to ignore: the Middle East needs to be handled with care but not to be neglected. Putin is positioning himself to play an influential role in the Middle East, not in order to expand his frontline of tensions with the West but rather in the hope of making a deal by proving that he has acquired a lot of cards in the region. He has in mind some type of parity partnership in overlooking the dangers of an explosive neighborhood. It is to his credit that he is offering a comprehensive strategy for how to confront ISIL and restrain Iran and its proxies. However this strategy is based on allowing Iran to continue its pursuit of hegemonic role, under Russian “adult supervision,” while weakening the US influence throughout the entire area all the way to the Persian Gulf.