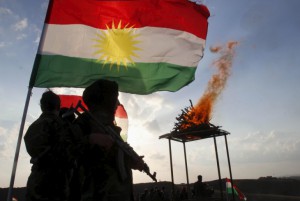

While the world grappled with the impact of Russia’s intervention in the Syrian civil war, a less noticed development in Iraq’s Kurdish north threatened to deal another blow to the U.S.-led coalition’s strategy to degrade and destroy Islamic State. Three days of violent protests in the autonomous Kurdistan region have revitalized old rivalries that undermine the effectiveness of its peshmerga forces—the coalition’s most trusted ally in Iraq.

The protests, which began as a peaceful show of growing public anger over an economic crisis compounded by political stalemate turned violent last week, with demonstrators attacking and torching several offices of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) across Sulaymaniyah province. Five people died and more than 100 were wounded in the unrest, reviving memories of internal strife and partition in the region, which has been an island of stability in Iraq and the wider Middle East since 2003.

The demonstrations have died down for now, but the political fallout has yet to sink in. The KDP, which is the region’s dominant political force, accused the rival Change Movement of orchestrating the violence for political gain and said it would pay the price. When the speaker of the region’s parliament, who belongs to the Change Movement, tried to enter the capital Erbil on Monday, his convoy was intercepted by security forces loyal to the KDP and sent back to Sulaymaniyah where the party is based. President Masoud Barzani chaired a meeting of the KDP politburo, which decided to unilaterally kick four ministers belonging to the Change Movement out of government.

They include Peshmerga Minister Mustafa Said Qader, who has been the main point of contact for the coalition assisting the peshmerga. The Change Movement, a relatively new party, entered the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) for the first time last year vowing to depoliticize the peshmerga, which owe allegiance to the KDP or the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which fought each other for most of the second half of the 20th century.

“In terms of creating a depoliticized force, it think it is fair to say that we are back to square one,” said Saeed Kakei, a senior adviser to the Minister of Peshmerga. “Our project of creating three depoliticised brigades supported by coalition forces has been put on hold. This depoliticized force could have created a balance between the PUK and the KDP peshmerga forces…Now there will be negative competition for weapons and other resources between the two competing forces. ”

Many of the commanders on the frontline against Islamic State today fought each other during the 1990s and still despise one another. The enmity between Barzani and the head of Change Movement, who used to be the top PUK peshmerga survives to this date. Both leaders are known to be highly stubborn and authoritarian.

Civil war also divided the Kurdistan region into two zones: one in Sulaymaniyah province controlled by the PUK and the other controlled by the KDP in Duhok and Erbil governorates, where hardly any protests took place. The two parties ran separate administrations until 2006, when they agreed to share power through the KRG and unify their peshmerga forces. But proper integration has been hindered by the entrenched partisan interests of each, despite years of pressure and encouragement from the United States.

Now the lines are being redrawn. Kamal Rauf, a long-time observer of Kurdish affairs who meets with senior politicians from all parties on a regular basis sees the danger that is lurking underneath. “In a situation like this, the Kurdish parties need to recall some of their forces with their military equipment from the front line with Daesh to secure the cities,” says Mr Rauf referring to the Islamic State by its Arabic acronym. Outside the KDP’s main base in the centre of Sulaymaniyah, peshmerga fighters can be seen with brand new German rifles provided by the coalition for the fight against Isis.

Adding fuel to the fire is the issue of Barzani’s presidency, which expired in August. Barzani ‘s mandate has already been extended once, bringing his time in office to more than a decade, but the KDP insists no-one else is fit to lead the region at such a critical time. Four other parties headed by the Change Movement say they are prepared to prolong his term for two more years on condition his powers are diluted, but the KDP has resisted that.

Throughout history, tribal or partisan interests have often trumped the higher the Kurdish cause. Commenting on the recent developments, prominent Kurdish novelist Bakhtyar Ali lamented: “What is happening in our political life these days… is the same thing that has happened throughout our history. Sadly our history goes in circles.”

newsweek.com