In 2012, Mohammad Matoh joined the Free Syrian Army. A year later he deserted finding work at a fast-food restaurant in Aleppo.

“Five members of our family were with the FSA. Now two are in Turkey after getting injured and two are still with the FSA,” he told Al Jazeera.

Matoh, 27, recalls other friends leaving as well. One of them, he said, “was forced to leave as a result of the inadequate salary, which was at best 18,000 Syrian pounds [$95] a month”. Matoh himself claims his salary started at only 8,000 Syrian pounds ($36) a month, before rising slightly.

Ahmad Jalal, 21, a field commander in the FSA, admitted that the salaries “can be as low as $50 a month, and sometimes salaries are not paid due to [lack of] support”.

The FSA, once viewed by the international community as a viable alternative to the rule of the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, has seen its power wane dramatically this year amid widespread desertions.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Aleppo, Syria’s largest city where many FSA soldiers are leaving the group, citing inadequate pay, family obligations and poor conditions.

In the past month, Russia’s bombing campaign against Syrian rebel groups and the FSA’s rejection of Russian invitations to participate in negotiations have further weakened it, raising questions about the group’s place in any future settlement.

On Wednesday, reports of a new Russian ‘peace plan’ were revealed. The eight-point proposal cites a constitutional reform process lasting 18 months that would be followed by presidential elections. According to the plan, ‘certain Syrian opposition groups’ should participate in the Vienna talks, expected to take place next Saturday.

Formed in August 2011 at the start of the Syrian civil war, the FSA comprises mainly defectors from the Syrian military. The group is viewed as moderate compared with the Islamist rebel groups that later emerged.

The FSA began suffering battlefield setbacks as early as 2013, including some to Islamist rebel groups in northern Syria. This prompted some members of the US House Intelligence Committee and the Obama administration to lose faith in the FSA.

A new US-backed alliance of rebel groups, called the Democratic Forces of Syria, was launched this year and only includes groups focused on fighting the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which is waging war against both the regime and several rebel groups throughout Syria.

The new Democratic Forces of Syria alliance does not include the FSA, which is concentrating on fighting the Assad regime.

But observers say that US support has not yet waned.

“I don’t think that the US has moved away for groups it has previously supported,” said Ammar Waqqaf, a member of the British Syrian Society and a frequent media commentator on Syria.

However, its exclusion from the Democratic Forces of Syria may lead to further isolation for the FSA. Waqqaf noted that “the US badly needs someone on the ground whom it can support and could mount some sort of a serious challenge to ISIL, hence the formation of new groups, including the Democratic ones”.

While no data exists on the number or rate of FSA desertions, Matoh speculates that 50 have left FSA units in the Aleppo area in 2015 alone. Fewer have defected this year due to the closing of the border with Turkey.

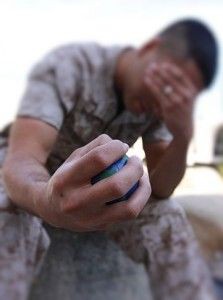

Other FSA fighters quit to provide for their families or because of the gruelling battlefield conditions.

“After the intensification of bombing in [Aleppo], fighters in bombed areas had to get their families out after injuries to them and shelling of their homes,” explained Jalal, the field commander. “The fighter needs to feed his family and the amount [of his salary] is sometimes not enough to do so or live on.”

Matoh recalled that days on the battlefield “would last 12 hours in cold conditions and with dust all over the place, after which we’d return to the base hungry. Then we’d go to sleep, get up and do it again the next day”.

Matoh, for one, does not fear retribution from the FSA, and has lived outside their command for more than two years. The calm tone Jalal takes towards defected fighters demonstrates that retribution might not be of major concern.

The desertions have taken a toll on the FSA’s strength. Determining the total number of FSA fighters is difficult, said Columb Strack, a senior Middle East and North Africa analyst at global information company IHS.

“The FSA is made up of more than 2,050 factions,” he said. He estimates that FSA groups in southern Syria have about 35,000 fighters. He noted that estimates for northern FSA groups prove harder because the FSA “is so fragmented there”.

Wayne White, a scholar at Washington’s Middle East Institute and a former deputy director of the US state department’s Middle East intelligence office, agrees. According to him, while the FSA’s exact numbers are hard to determine, they are weaker than their Islamist counterparts.

“The FSA, compared with various other rebel groupings, such as ISIL, al-Nusra, and various moderate Islamist factions is relatively weak. The current total of FSA combatants in Syria is not precisely known,” he told Al Jazeera.

FSA units vary greatly in their equipment and battle-readiness, Strack added. “There are small local factions armed with AK-47s, and other US-backed ones armed with tanks.” Some FSA units, he said, consisted of “localised militias of 10 to 20 guys who don’t move out of their village”, while others are “much more capable factions of former officers”.

Desertions from the FSA have been common in Aleppo and northern Syria more generally, where Islamist groups such as the Nusra Front, which is affiliated with al-Qaeda, are more powerful.

Wayne attributes the relative strength of Islamist rebels to better arms and funding, plus Western reluctance to fund rebels. “The US and the West became resistant to supplying secular rebels with large quantities of arms because they feared such arms could fall into extremist hands,” he told Al Jazeera.

Moreover, he noted that the better funding, arms and strength of Islamist rebels had made “far more recruits – and even many moderate combatants – join such groups”, since 2012, whereas the FSA is currently dealing with many desertions.

Some FSA-allied commanders agree that fragmentation is hurting the group and weakening its image in the eyes of the international community.

“We are not unified and therefore will not get stronger,” said Suhaib, a commander in the Jaysh al-Islam coalition who declined to give his full name. “In my opinion, the international community’s perspective that the FSA is weak and ineffective on the ground is because of the FSA’s failure to unite all the factions.”

Jaysh al-Islam is part of the Islamic Front, one of the main rebel groups and an ally of the FSA. It has acknowledged an alliance with the FSA, despite high tensions at times. Suhaib serves in one of their Aleppo area units.

A stalemate currently prevails in Aleppo, with no side making notable advances.

On Wednesday, however, the Syrian army achieved what many observers considered a military breakthrough when it recaptured a northern military airbase that had been besieged by ISIL since 2013.

“Army and the armed forces eliminated large numbers of ISIL terrorists and make contact with the forces defending Kweires Airport in Aleppo’s eastern countryside,” the Syrian Arab News Agency said on Tuesday.

With no end in sight to the desertions and disunity, and attacks from both government and other rebel forces, the FSA faces challenging times ahead.

“If we don’t work together,” declared Suhaib, “we’ll die together”.

aljazeera.com