According to studies, the success rate of terror groups in achieving their political objectives is 4-7%. So why do terrorists bother?

This week has seen a resurgence of terror groups in Africa, after a lull of several weeks.

Over the weekend, al-Shabaab in Somalia killed at least 12 people in a raid on a hotel in Mogadishu popular with government employees, members of parliament and businessmen. The militants are said to have packed a vehicle full of explosives and rammed their way into the heavily fortified hotel compound.

In Egypt, investigators are still trying to piece together what exactly happened when an airliner carrying 224 people crashed in the Sinai peninsula, killing everyone on board. Authorities still say it is too early to conclusively determine the cause of the crash, but it looks like an explosive device may have been on board, causing the aircraft to split apart mid-air.

The Islamic State (also known as ISIS, ISIL or Da’esh) continues to claim responsibility for the attack, the most recent statement from the group has them challenging sceptics to prove otherwise. IS has a foothold in parts of Libya, where lawlessness in much of the country has given an opportunity for the group to establish a base there.

And in Nigeria, terror group Boko Haram has released photos apparently showing a rocket-making factory in north-eastern Nigeria, the BBC reports.

The group has used rocket-propelled grenades in the past and the photos seem to indicate that members of the group have the technical know-how to manufacture weapons; an inscription on one of the machines shows the abbreviation of Government Technical College Bama (GTCB). Bama is a town in the northeastern state of Borno that has repeatedly been overrun by Boko Haram.

These three incidents in the space of a week suggest that terror groups in Africa are far from being defeated – Boko Haram pledged allegiance to IS last year, when the Iraq and Syria-based terror group emerged as the baddest jihadists of them all, at least for now.

Reports from Somalia suggest a rift growing within in al-Shabaab, with one faction wanting to pledge allegiance to IS, while the other wants to remain affiliated with al-Qaeda.

Notoriety

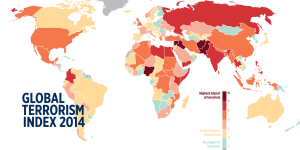

Even as terror groups in Africa resurge and re-energise themselves – partly feeding off the notoriety of IS – history suggests that they are ultimately doomed to fail. The success rate of terrorism as a political strategy is dismal, studies suggest.

In 2006, an article by Max Abrahms titled ‘Why Terrorism Does Not Work’, analysed the political plight of 28 terrorist organisations, as designated by the U.S. State Department. His analysis found that their success rate was about 7%.

A larger study by scholars Seth Jones and Martin Libicki looking at a larger sample – 648 groups identified in the RAND-MIPT Terrorism Incident Database, active from 1968-2006 – found only 4% obtained their political demands.

In fact, the vast majority of terror organisations have perpetrated terrorism for decades without any real signs of political progress.

Moreover, the successful groups used terrorism only as a secondary tactic. Although non-state actors are known to employ a hybrid of asymmetric tactics, all of the politically successful terrorist organisations directed their violence against military targets, not civilian ones.

So why do terrorist groups continue with a strategy that has such an abysmal success rate?

One theory is that terrorists are irrational, unhinged, brainwashed people, who simply want to cause mayhem and destruction. But again, the science contradicts this view.

Cognitively normal

Numerous researchers concur that terrorists do not typically exhibit mental illness or psychopathy, and seldom do they have “an emotional disturbance that prevents them from differentiating between reality and imagination.” Psychological assessments of terrorists indicate they are cognitively normal (outside their use of terrorist tactics).

The puzzle of terrorism is that despite the presumed rationality of the perpetrators, this mode of violence does not seem to advance the group’s given political cause.

Scholars Max Abrahms and Karolina Lula suggest that the reason for this is that terrorist leaders overestimate the odds of victory by drawing false analogies from successful guerrilla campaigns, which are indeed comparatively profitable.

The distinction is important to make – terrorism, as understood today, is the violent action of armed groups primarily on civilian targets, while guerrilla attacks focus on military targets.

The golden age of guerrilla movements was just after World War II, when national liberation movements in Africa, Asia and the Middle East achieved independence for their countries despite their military inferiority.

The National Liberation Front (known by its French initials FNL) in Algeria managed to kick the French out by a series of assymetrical attacks; the Portuguese in Africa were drained financially and exhausted militarily by the relentless attacks of guerrilla fighters in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau.

And in Kenya, though the Mau Mau fighters technically lost the war, the burden on British finances in retaliation campaigns made it just too costly to hold on to the Kenya Colony.

Humiliated

In the 1980s, the mujahideen resistant fighters in Afghanistan put up a sustained insurgency against the Soviet forces that had invaded the country, bleeding them so badly that the Soviets were forced to withdraw in 1989.

In 1993, the Americans were humiliated in Somalia in the infamous Black Hawk Down incident and scurried away; more recently, assymetrical attacks by Hezbollah in Lebanon against the Israel Defense Forces compelled them to withdraw from Lebanon in May 2000.

Abrahms argues that terror groups today mistakenly conflate these guerrilla victories with their own chances of success, without making the distinction between civilian targets and military ones.

But killing civilians does the complete opposite of what it is intended to – it dramatically reduces the chances of a target government making political concessions, and instead increases the appeal of hard-line, right wing politics, particularly if the group is looking to achieve “maximalist” demands – a battle over values, ideology and beliefs, as opposed to limited demands over territory.

The reason for this is that the human psyche is wired for correlation and inference: if darkness is falling and someone lights a candle, I will infer that the person wants some light in the room.

Similarly, the immediate horror of the terror attack, including the death of innocent people, mass fear and anxiety, and erosion of civil liberties, makes civilians believe that this is the ultimate objective of the terror group.

Former US President George W. Bush said it many times, that any group that deliberately attacks American civilians was evidently motivated by the desire to destroy American society and its democratic values.

Political jujitsu

In actual fact, terrorism is an assymetrical strategy in which the perpetrator’s actual target (civilians) isn’t their real target (a government or political system); the terrorist is trying to provoke an excessive reaction from their real target, in so doing turn the target’s strength against itself in a form of political jujitsu, as brilliantly articulated by David Fromkin in his 1975 essay ‘The Strategy of Terrorism’, published in Foreign Affairs.

But it doesn’t work because target countries see the horrifying negative consequences of terrorist attacks on their societies and political systems as evidence that the terrorists want them destroyed, and that understandably makes them dig in and refuse to negotiate, when the actual goal of the terrorist group could be to protest foreign aggression or poverty.

So what do African terror groups want? Al-Shabaab is fighting to overthrow the internationally recognised government in Somalia, and has also stated that they want all foreign armies out of Somalia, and ultimately to establish an Islamic state.

Boko Haram wants to establish shariah law over northern Nigeria and to establish a caliphate. IS has already declared a caliphate, has massacred “apostate” Muslims, and wants to essentially bring about a return to the golden age of Islam.

All these are maximalist goals, but history has taught us that the more maximalist the demands of a terror group, the less likely that they will be achieved, because people do not make concessions when you threaten the core of their existence – their values, beliefs and ideology, particularly if they have government machinery in their corner.

They fight back.

mgafrica.com