After more than a decade of covert operations, U.S. activity in Somalia sprang into life this week with two high-profile assaults on the militant group Al-Shabab.

First, the Pentagon confirmed a series of drone and manned air strikes on an Al-Shabab training camp in Hiran, south-central Somalia, on March 5. The U.S. claimed that at least 150 militant recruits were killed in the strikes, though Al-Shabab disputed the death toll. The strikes were quickly followed up by a daring helicopter raid overnight on Tuesday, when joint U.S. and Somali forces assaulted a base held by the militants in Awdigle, south of Mogadishu. Again, the death tolls were a matter of dispute, with Somali government officials claiming as many as 15 fighters were killed but the armed group saying there was only one casualty.

Even if the U.S. does not carry out another single operation in Somalia in 2016, these two incidents make it the deadliest year in terms of casualties inflicted by American forces in the Horn of Africa state in almost a decade. But Washington plainly has many other pressing foreign policy engagements—the U.S. is leading a grueling bombing campaign against the Islamic State armed group (ISIS) in Syria and Iraq (and, increasingly, in Libya) and is also providing tactical support in the fight against Boko Haram in West Africa. So why is the U.S. bothering with Somalia at all?

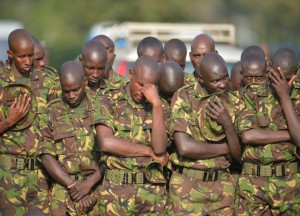

Part of the answer lies with the African Union (AU). The body’s military force in Somalia—AMISOM—is looking increasingly incapable of dealing with a resurgent Al-Shabab by itself. The 22,000-strong multinational force successfully drove the militants out of major cities in Somalia, including the capital Mogadishu in 2011. But in the past year, the momentum appears to have shifted, in particular with three instances of Al-Shabab fighters overrunning AMISOM bases in Somalia.

In June 2015, militants killed at least 50 Burundian soldiers and took control of their AU base at Leego, 130 kilometers (81 miles) south of Mogadishu. A few months later, the group overran the AU base patrolled by Ugandan soldiers in Janale, southern Somalia, claiming to have killed 70 soldiers in the process. Finally, in January, Al-Shabab militants besieged the El Adde base in the Gedo region of Somalia, close to the Kenyan border. Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud recently admitted that Al-Shabab may have killed up to 200 Kenyan soldiers in the raid, which would constitute the one of the single greatest losses of life in Kenyan military history. (Kenya has so far declined to give a definitive death toll for the attacks.)

“The U.S. are increasingly getting involved because of perceived AMISOM weakness, and the Americans are seeing that Al-Shabab are growing in strength and can manage these type of attacks,” says Stig Jarle Hansen, an Al-Shabab expert and author of Horn, Sahel and Rift, about African armed groups.

Hansen cites an incident in February, when Al-Shabab took control of the Somali port city of Marka with zero resistance from AMISOM troops, who reportedly withdrew from the town before the militants arrived. (AMISOM denied that its forces had withdrawn, saying that troops occasionally “readjust their positions,” and also denied that Al-Shabab took control of Marka.)

The incident, according to Jansen, highlighted a lack of coordination between AMISOM and Somali armed forces and police. “That’s quite shocking and it shows something very negative about the state of the Somali police and the state of the Somali army. It has improved, but it’s not good enough to be efficient,” he says. His comments echo those made by General David Rodriguez, head of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), to the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee on Tuesday. Rodriguez said that AMISOM’s effectiveness was being limited due to its troops being “overstretched,” and that the weakness was exacerbated by “endemic deficiencies” within the Somali National Army, which Rodriguez said is “challenged by leadership, logistical support, and clan factionalism.”

Al-Shabab’s broader affiliations have been a matter of much dispute in recent months. The Somali group officially pledged allegiance to Al-Qaeda in 2009 but has been the subject of repeated overtures from ISIS, which has tried to convince the group’s leadership to switch allegiances. In the main, Al-Shabab has resisted, and only a small number of fighters have pledged their loyalties to ISIS.

According to Hansen, Al-Shabab remains one of only three noteworthy Al-Qaeda franchises in a global militant landscape increasingly dominated by ISIS, the others being the North African branch (Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM) and the branch active in Yemen (Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, or AQAP). “By hitting Al-Shabab, you are also hitting the image of Al-Qaeda internationally,” says Hansen, who also points out that, in January, the Somali group used a propaganda video to try to incite U.S. Muslims to violence. The film featured comments by Republican presidential contender Donald Trump, who proposed a total ban on Muslims entering the country, and told American Muslims that their country would eventually turn on them.

So does the U.S.’s recent flurry of activity in Somalia mean it will now engage in a sustained campaign against Al-Shabab? Not likely, according to Roland Marchal, an expert on Al-Shabab at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (known as Sciences Po). The U.S. has been carrying out covert operations in Somalia since at least 2007, but the most drone strikes it has launched in one year was 12 in 2015, according to data gathered by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Somalia is “not high” on America’s list of priorities, says Marchal, and the recent interventions represent less of a strategy and more of a “way to do something big” to intimidate the group. “They [the U.S.] will try to repeat that. Not so much 20 strikes a year, but often enough to scare Al-Shabab fighters and maybe push members to disband,” says Marchal.

newsweek.com