n 28 February, President Donald Trump declared: “We just took over 100 percent caliphate.” He was talking about the lands that ISIS controlled in Syria and Iraq, although he wasn’t exactly right. But now the Pentagon’s Africa Command (Africom) says that ISIS is already reconstituting itself in West Africa, even to the extent of setting up a new caliphate, like reported by opendemocracy.net. So far it is much smaller than the former Middle Eastern territory – but there are some worrying comparisons to be drawn.

The original manifestation of ISIS came out of nowhere between 2011 and 2014, originating in the remnants of al-Qaida in Iraq and using the chaos in Syria and the despair of the Iraqi army to take control of a swathe of land from Raqqa in northern Syria to Mosul in Iraq. At its peak it controlled an area almost as large as the UK with a population of six million.

The brutality of the regime, not least against minorities such as the Yazidis, was apparent early on. However, it was also notable for its technocratic competence and maintenance of order. If people accepted the rigidity of the rule and did not step out of line, their lives were at least more ordered and predictable than the chaos of post-war Iraq.

It wasn’t that different to the way in which the Taliban had established a brutal yet coherent order across much of war-torn Afghanistan in the mid-1990s. In the case of the ISIS caliphate it was much aided by a cadre of Iraqi technocrats who had run many of the public services under the pre-war Saddam Hussain regime in Iraq. Many of these were then summarily dismissed by the US Coalition Provisional Authority in 2003 because of their membership of the Ba’ath Party, and it was these people who were willing to throw in their lot with ISIS.

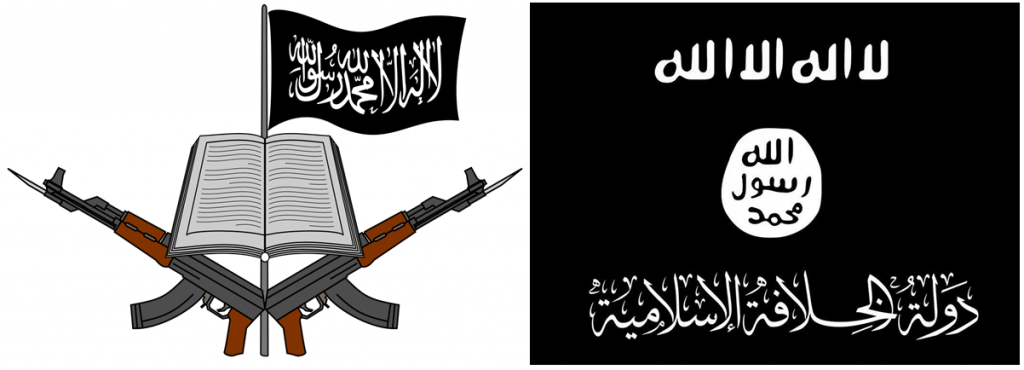

For a few years the caliphate survived and was the core symbol of the ISIS approach. Where al-Qaida was all about establishing Islamist rule by overthrowing existing regimes, ISIS chose to capture territory across two countries and establish its version of ‘boots on the ground’. It did not last as the US established a new military coalition in 2014 and started a four-year air war that killed over 60,000 ISIS supporters and enabled Iraqi, Kurdish and other forces to overrun the caliphate.

Fertile ground

The Trump administration presumed the enemy defeated thanks to that air war, even though ISIS continued to be active in Syria and Iraq and has links with like-minded groups in Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Sri Lankan and Afghanistan. It even had a part in the extraordinary takeover of the city of Marawi in the southern Philippines in 2017, which lasted four months and left the city in ruins. Now, though, ISIS has gone much further.

Over the past decade a number of countries in West Africa and the Sahel have experienced Islamist insurgencies, including Mali, Chad, Burkina Faso and Niger. The most developed and sustained of these has been the Boko Haram movement in northern Nigeria. It has been a major problem for the government in Abuja and has been greatly aided by its ability to recruit from the tens of thousands of young men who have at least a basic education but little or no life prospects.

On a smaller scale this has also been true of other states across the Sahel. The most common response has been military repression, with the US, France and other western states using special forces, attack helicopters and armed drones, as well as training and equipping the armies of local states.

Progress against the insurgents has been slow – so slow that the Trump administration has already withdrawn some of its forces and plans to bring more back home, in line with the US president’s distaste for small wars in far-off places. This has not been well received by Africom, and a recent Oxford Research Group briefing reported that the head of US Special Operations in Africa, Major-General Marcus Hicks, stated bluntly: “I would tell you at this time we are not winning.”

That briefing also quoted an experienced journalist, Ruth Maclean, on an underlying reason for the success of Islamist movements in Burkina Faso. She wrote: “The country’s poorest regions in the north and east have been neglected, with the government providing minimal health services, education, jobs and infrastructure. Locals have in response taken up arms and forged links with militant groups who promised, and delivered, more services than the state.” The UN estimates that 150,000 Burkinabe people stay away from school and 100,000 people have been displaced from their homes by the violence.

The new franchise

Fifteen hundred kilometres to the east, in a largely semi-arid region stretching from north-east Nigeria into Chad and Niger, Africom now reports that ISIS has gained a major foothold and is beginning to create a new caliphate. According to the Pentagon’s Stars and Stripes journal:

Islamic State militants in West Africa are gaining the upper hand, carving out a ‘proto-state’ in northern Nigeria where government forces have been overwhelmed by attacks, US military officials and security analysts say.

ISIS-West Africa, which broke away from the militant group Boko Haram three years ago, continues to launch high profile attacks that have placed the Nigerian military ‘under tremendous strain,’ according to Stuttgart-based US Africa Command.

One of Africom’s concerns is that the ISIS affiliation could lead to “funds, fighters, weapons or other assistance from other components of the self-described Islamic State”.

The independent International Crisis Group paints a similar picture in a recent report. It says ISIS-West Africa has established itself as a separate entity from the Nigerian government and other paramilitary groups, and has won some trust among local populations: “It digs wells, polices cattle rustling, provides a modicum of health care and sometimes disciplines its own personnel whom it judges to have unacceptably abused civilians.” It imposes taxes but provides services in return. Recruitment and popular support as a result has risen to the extent that, according to the ICG, a “jihadist proto-state” now exists.

Africom estimates ISIS-West Africa’s paramilitary strength at 3,500 to 5,000 fighters and that in the past nine months “they have overrun dozens of Nigerian army bases and killed hundreds of soldiers”. The International Crisis Group, echoing Maclean’s reporting from Burkina Faso, puts it this way: “The deeper [ISIS-West Africa] sinks its roots into the neglected communities of north-eastern Nigeria, the more difficult it may be to dislodge.” Nearly eighteen years after 9/11, the war goes on.