Like 9/11 for New Yorkers, the Paris attacks of November 2015 have become that rare thing for city slickers — a topic of conversation in which everyone can participate. There are two million Parisians, each of whom has a story about the night suicide bombers and gunmen killed 130 people at cafés, restaurants, the Stade de France and the Bataclan music hall.

Some offer a poignant mix of tumult and tragedy, like the one my high school friend tells of diving under a table at a café when a terrorist opened fire on drinkers with an assault rifle. (She performed CPR on a shooting victim who ended up dying from loss of blood). Others, like mine, are less riveting. After making sure my friends and family were safe, I got to work covering the story. The tales all have one thing in common: a moment in which the person recounting it is struck by the enormity of what occurred.

In my case, it came more than 24 hours after the attacks. After news of the shooting broke, my girlfriend and I hunkered in our apartment: me to write and report, her to comfort and host friends who kept dropping by. It was only the next day, when a couple of German friends called and suggested getting together, that we ventured out into post-attack Paris. Our street is usually a party strip. It was utterly silent. Bars, restaurants and hotels that do brisk business even under driving rain were closed and empty. The scene — eerily quiet, cinematically barren — yanked me out of the story I had been writing and into the reality of the tragedy that had engulfed the city.

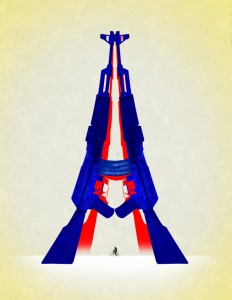

As we turned left onto Avenue de Clichy, I tried to joke about it, noting that it looked like the perfect setting for a sequel to the zombie movie “28 Days Later.” My girlfriend didn’t laugh. An awful thought crowded my mind: The terrorists had won. With a few cell phones, Kalashnikov rifles and suicide vests, they had silenced this proud and insolent city and reduced its residents to cowering in their apartments when they should have been making noise in the streets.

Once we got to our friends’ place, just a few blocks away, the mood lightened. We drank, shared our stories of the night, and even managed a few relieved laughs. But there our conversation had a melancholy undertone: We kept coming back to whether the violence would trigger a civil war. Fortunately, it didn’t. Neither those killings nor any of the bloodshed that followed escalated into all-out conflict between French Christians and Muslims (though the head of domestic intelligence warned in testimony to a parliamentary committee this past summer that it was a possibility). But they primed us for the possibility that tragedy could strike at any moment, and they made all Parisians inordinately vigilant.

In the metro, people stared harshly at young men wearing beards, or, more ominously, beards paired with tracksuits and backpacks (the “jihadist look,” according to surveillance footage captured of two assailants who had ridden the metro after the attacks.) All of us suddenly became security experts who knew how to identify a soft target. Some of us — or maybe it was just me — would occasionally be stricken by sudden rushes of sadness. When I first went to see a movie at a theater a few weeks after the attacks, I felt proud to be relaxed enough to be keeping up my old habits. But when a young man entered the screening room late, I was gripped by terror. I had to reason with myself that, by staying until the end of “Crazy Amy,” I was doing my part in France’s fight against terrorism.

A year later, are we still sitting on the edge of our seats, half-expecting a terrorist to enter the room? No. Take a walk on any nightlife stretch in the French capital and you will see café terraces full of young people drinking and smoking as patriotically as before. The fact that Parisians returned to their old haunts so rapidly after the attacks was widely interpreted as proof of the French Republic’s resilience in the face of terror. The Moveable Feast was still on the move. The City of Light was shining as brightly as ever. Take that, terrorists, we said, raising our glasses of wine.

But it would be wrong to say that France simply snapped back to the way it was before the attacks. The place has changed more profoundly than most of its residents are willing to admit. Repeated acts of violence have robbed the French of their presumption of safety. Despite admirable efforts to respond to the terrorist threat in a measured way, to avoid reaching Israeli levels of obsession with security, France has mutated into a different version of itself: angrier, ready for more violence and locked into increasingly hostile and polarizing debates.

The most shocking thing about terrorism in France in 2016 is that terrorism is no longer shocking. It can be terrifying, distressing and infuriating, sure. But the steady drumroll of attacks that started in early 2015 — from the Charlie Hebdo and Bataclan attacks in Paris to the massacre on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice to the murder of a Catholic priest in his church in Normandy — have burned away our capacity for shock. Instead of reacting to attacks with surprise, the French nation now responds with ever shorter loops of grief, outrage and calls to hang the bad guys.

The kumbaya spirit of the post-Charlie Hebdo period, when more than a million people marched behind a procession of European leaders to proclaim their love of free speech, is gone. After a man killed 86 people by driving a cargo truck into a crowd celebrating Bastille Day in Nice, opposition politicians didn’t wait 24 hours before slinging mud at the government, accusing it of “criminal negligence” for having let the attack happen. Needless to say, there was no new march — the state of emergency made sure of that.

France may feel that it looks the same in the mirror, but the rest of the world sees it differently. At recent a dinner in New York, I was asked by a worldly American whether it was dangerous where I live. My reflex was to accuse him of being naive, but I caught myself. The fact is: Yes, France is dangerous, compared to most other Western countries. I just don’t live in a constant state of alert.

politico.eu