The pilots stared ahead at the night sky, their eyes scanning an expanse of black that was interrupted by the glittering outlines of northern Iraq’s cities and towns.

On the plane’s port side, a large spiderweb of yellow and neon lights came into view.

“That’s Mosul,” said Col. Thaer Hussein, commander of the C-130J Super Hercules turboprop lumbering toward Islamic State’s Iraqi capital.

In the plane’s loading bay, Crew Chief Sadeq Abbass and Maj. Mohammad Ismail attached themselves to cables clipped to the floor, donned gray oxygen masks and heaved the aircraft’s side doors open.

As the wind roared through the plane’s belly, bringing down the temperature to 23 degrees and leaving the air thin, the two officers turned to their cargo: hundreds of boxes of leaflets, divided into three large piles.

Over the next hour, they would throw them over 16 cities and towns in Nineveh province, all held by Islamic State, as part of the government’s largest “psy-ops” offensive against the militant group.

In the battle to defeat Islamic State, which the government calls “Daesh,” Iraqi forces have taken aim at the militants not only with bombs and bullets, but also through a multi-pronged media war to deflate the group’s “bogeyman” image.

The efforts serve as a counterweight to Islamic State’s media machine, a juggernaut that produces high-quality videos, photo essays and magazines disseminated via a Hydra-like social media network.

Even now, despite clearly being on the back foot in Syria, Iraq and Libya, the militants maintain their media presence and have vowed that, if ousted from their bastions, they will revert to a shadowy insurgency while continuing to push disciples in the West to conduct “lone-wolf” attacks.

It was a little more than two years ago that Islamic State stormed Mosul, prompting tens of thousands of Iraqi soldiers to flee for their lives in the face of an onslaught by a ragtag army of about 1,500 militants in pickups.

“What happened in June 2014 was a function of psychological operations by Daesh that were able to cast terror, fear and confusion among both the armed forces and our society,” said Said Jayashi, a consultant to the Iraqi government’s Psychological Warfare division, in a phone interview on Wednesday.

The easy capture of Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, pushed the extremist group to proclaim the establishment of its caliphate over swaths of Iraq and Syria a few weeks later.

It also prompted the Iraqi government to bring together “a group of experts, composed of university professors, specialists in psychological, social and media sciences as well as intelligence and security personnel,” said Jayashi. They were tasked with producing propaganda to counter Islamic State.

Much of the pro-government propaganda is woven into everyday life in government-controlled areas of the country: Songs mock Islamic State (one of them, “Daesh the Dirty,” insists its fighters smell and flee at the sight of loofahs), stern-eyed generals and analysts perennially predict the group’s demise on talk shows, and billboards extol the heroism of Iraq’s security forces.

As the battles to take back Islamic State areas began in 2015, Jayashi said, “military operations had to be supported by media and psychological operations to confuse the enemy” and to reach residents living under Islamic State rule. To do this, the government uses text messages, radio and leaflets.

The leaflets, especially, have played a central role. Over the last two years, the government says, its planes have cast more than 40 million of them over Islamic State areas.

As the government’s campaign has progressed, the airdrops have served as a prelude to the security forces’ advance, leaving a paper trail extending from parts of the Syrian-Iraqi border to Salahuddin province, Ramadi and Fallujah.

With the government poised to launch its offensive on Nineveh province, Jayashi said, “we are covering Mosul and surrounding areas.”

The leaflets bear different messages. Some, Jayashi said, “expose the defeats of the enemy so as to confuse them, and show the truth of what is happening outside these cities.”

One leaflet, distributed over Mosul in June, told beleaguered residents that it was “high time … that you all stand on the land of your pure city as one hand against Islamic State” and “rule the city and decide its fate.”

Others give more practical advice, such as those informing people of the location of humanitarian corridors or reminding them to take personal documents before evacuating their homes. Those are usually thrown 72 hours before ground forces begin their incursion on a city.

The mission Tuesday, according to Hussein, the C-130J pilot, set out to drop 7 million leaflets — 400 cartons.

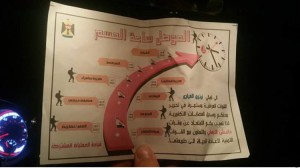

One side of the leaflet was dominated by the Iraqi flag. On its back were dates of the government’s victories since October 2014.

An arrow pointed to a clock with the words “Mosul: The Hour of Victory” emblazoned on top. The text at the bottom warned residents to stay away from “the headquarters of the terrorist Daesh” and to cooperate with security forces when they arrive “to bring life back to normal” in the city.

Although the leafleting would not involve direct clashes with Islamic State, it was not without danger. In a ground briefing before the flight, Hussein told reporters that he would not descend below 16,000 feet so as to avoid ground fire.

“Daesh has Chinese-made antiaircraft missiles, so we don’t want to risk getting hit,” he said.

With the plane in position over its target, officers Abbass and Ismail began to grab boxes and throw them out of the side door.

Ismail explained there was no danger of the cartons falling — and killing — unsuspecting citizens below; the wind would quickly rip them apart.

Events soon proved he was right: One of the boxes hit the lip of the doors, tearing its side and spewing leaflets in a whirling vortex of paper.

Suddenly, an unintelligible message came over the plane’s public address system, followed by an abrupt movement. In the cockpit, Hussein, seeing the flashes of what appeared to be antiaircraft fire, had taken the plane up to safety. Although only a little more than two-thirds of the boxes had been deployed, the mission was over.

The next day, the local news outlet Sumariyah News quoted a source in Nineveh province who said that Islamic State had mobilized its cadres to collect and destroy all the leaflets in their areas.

Any resident found with a leaflet, the source said, would be lashed 20 times.

latimes.com