Daesh has been routed in Iraq. On 5 October, the militant group lost the northern town of Hawija – its last urban stronghold after Iraqi forces recaptured Mosul and Tal Afar earlier this year. The brutal battles for these cities have been well documented. Less noticed, however, has been how the near-total defeat of Daesh is reshaping political and sectarian alliances in the region, like reported by middleeastmonitor.com.

The rise and fall of Daesh has had a sobering and unifying effect on relationships between Sunnis and Shi’ites. In Iraq, where thousands died in the vicious sectarian war that followed the fall of Saddam Hussein, residents of the mainly-Sunni cities of Mosul and Hawija nonetheless jubilantly welcomed the mostly-Shi’ite Iraqi forces who freed the cities from the Sunni extremists of Daesh. “They helped liberate us,” one Hawija Sunni leader told the New York Times of the fighters. Nor does a Shi’ite backlash against Sunnis seem imminent given Shi’ite recognition of Sunni suffering in the Daesh-occupied cities.

The Daesh experience has affected Iranian politics too. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei seemed to show a softer attitude toward Sunnis in a rare pronouncement – seen as carrying the weight of a fatwa – publicly prohibiting any discrimination against minorities. Sunnis have fewer rights than Shi’ites in Iran, and Khamenei’s August comment was made in response to an inquiry by Molavi Abdul Hamid, a prominent Sunni cleric from Iran’s impoverished Sunni-dominated Sistan-Baluchistan province on the Pakistan border. In Syria too, Daesh’s faster-than-expected battlefield defeats suggest that the group does not enjoy much local support among the Sunni tribes and populations it has been ruling for the past couple of years.

The biggest changes can be seen in Iraq, where Shi’ite leaders’ attempts to develop a post-Daesh foreign policy are driven in part by fear of Iran’s growing influence and in part by the Daesh-inflicted suffering in Iraq. Many observers believe that the pursuit of sectarian policies at the expense of Iraqi Sunnis – as systematically practiced under the former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki – expedited the rise of Daesh.

The result of the new dynamic is that Iraq’s main Shi’ite leaders are distancing themselves from Iran as they make once-unthinkable overtures to the region’s Sunni Arab bloc. In one of the latest signs of that shift, Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar Al-Abadi declined Tehran’s official invitation to take part in President Hassan Rouhani’s second-term inauguration ceremony on August 5. Such a refusal would have been unimaginable a few years ago.

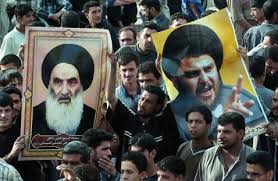

Similarly, prominent Shi’ite leaders such as Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani and Moqtada al-Sadr snubbed Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, the newly-appointed chairman of Iran’s Expediency Council – a governing body set up to mediate disputes between Parliament and the Council of Guardians over whether planned legislation conforms with Islamic law – during an official visit to Iraq as the envoy of Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei.

Underscoring the point, Baghdad publicly slammed a deal made by Hezbollah, Iran’s chief proxy in the region, to evacuate a group of Daesh fighters from Lebanon to eastern Syria, near the Iraqi border. The Tehran-backed agreement was “unacceptable” and “an insult to the Iraqi people,” Prime Minister Abadi said in August.

Iranian influence on Iraq’s domestic politics is shrinking too. Ammar al-Hakim resigned as head of the Tehran-backed Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq – the country’s largest Shi’ite party – a month after a June meeting with Khalid al-Faisal, the governor of Mecca and an informal advisor to Saudi Arabia’s King Salman. Hakim promptly went on to form the National Wisdom Movement, a political party to “embrace” all Iraqis.

At the same time, Iran-funded, Shi’ite-dominated militias known as Popular Mobilization Forces are divided over whether they should be integrated into the regular Iraqi army – a measure that would loosen Iran’s foothold in Iraq’s security apparatus – or whether they should remain independent of the Iraqi government. Groups loyal to Sadr and Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani have started taking steps to register with the army; those led by Hadi al-Amiri of the Badr Organization and Qais al-Khazali of Asaib Ahl al-Haq remain in the pro-Iran camp.

Against this backdrop, Iraq is trying to improve its ties with Saudi Arabia. In addition to several recent diplomatic visits between the two countries, including one by Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to Riyadh, Moqtada al-Sadr – an influential Shi’ite cleric with a large following among Iraq’s urban poor – made rare and well-received visits to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. After meeting with Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, Sadr issued a statement saying that he was “very pleased with what we found to be a positive breakthrough in the Saudi-Iraqi relations,” and that he hoped it was “the beginning of the retreat of sectarian strife in the Arab-Islamic region.” Sadr’s 13 August meeting with Emirati crown prince Zayed al-Nahayan appeared equally successful. “Experience has taught us to always call for what brings Arabs and Muslims together, and to reject the advocates of division,” Nahyan told Sadr, in a veiled reference to Iran as one of the dividers.

It is clearly in Iraq’s strategic interests to diversify its relationships beyond reflexive sectarian or ideological lines. Improved ties with Riyadh pave the way for Baghdad to receive much-needed financial aid from Saudi Arabia and establish an economic relationship that could help counter the political and military influence established when Iran cultivated Shi’ite proxies to fight US-backed forces in Iraq. The outreach can also signal to Iraq’s Sunni minority that the Baghdad government is not an Iranian stooge.

Iraq’s post-Daesh foreign policy could have broader regional benefits too. For Riyadh, closer ties with Baghdad can help the Saudi leadership feel less threatened by Iran’s rising influence and the perception that Riyadh’s share of regional power has diminished as a result. That in turn may lead to a thaw in Iranian-Saudi ties and a broader contribution to regional security.

While this balancing act could help mitigate the Shi’ite-Sunni tensions in the Middle East, it would be naïve to assume that deeply-rooted ideological and religious schisms will disappear anytime soon. The recent Kurdish referendum, for example, already seems to have made Baghdad more willing to invoke Iran’s military and economic leverage to dissuade Iraqi Kurds from declaring independence. Nor will Iraqi Shi’ites quickly forget their anger over actions like Riyadh’s unequivocal support for the Sunni-dominated regime of Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war of 1980 – 1988, or Saudi Arabia’s harsh treatment of its Shi’ite minority.

Nonetheless, the fact is that neither Riyadh nor Tehran can achieve sustainable hegemony in the region at the expense of the other. It’s ironic that it may be the routing of extremist Daesh that serves as the catalyst to ease the bitter sectarian rifts that have divided them for so long.