There are two principal foreign actors operating in the Sahel: the EU and the United States. President Obama took considerable interest in Africa, just like his predecessor George W. Bush who allocated billions of dollars for President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which provided antiretroviral treatment and care for HIV/AIDS patients, overseeing such initiatives as Power Africa, like reported by aspistrategist.org.au. This was a $7 billion program aimed at doubling access to electricity across sub-Saharan Africa. At the same time, Obama also authorised a greater US military presence in the Africa by dispatching drones, special forces and private contractors to the area with the aim of countering the presence of salafi–jihadi groups.

It’s safe to assume that President Trump is unlikely to have a great interest in Africa, although three of the countries on his proposed travel ban list are African: Libya, Somalia and Sudan. Trump’s foreign policy agenda, such as it is, focuses more on the Middle East, and specifically on the Islamic State as it operates in Iraq and Syria, which it seeks to annihilate. Moreover, the Trump State Department has been marginalised: hundreds of posts remain vacant, primarily because the administration hasn’t nominated anyone for the various positions that are available within the department. Additionally, the Trump administration appears committed to massive budget reductions, which includes eliminating such entities as the African Development Foundation, a government agency that provides grants to support community enterprises and small businesses across Africa. In 2016, the foundation supported 500 businesses that generated US$80 million in new economic activity.

In respect of the Sahel, recent reports suggest that US diplomats, with support from the UK, resisted a UN Security Council resolution authorising a West African force to counter terrorism and trafficking. Official it seems that American opposition to the resolution is based on the claim he draft French resolution was unwarranted and too broad, although one should add that the US is seeking to have a reduction in the $7.8 billion UN peacekeeping budget, to which is contributes 28.57%.

One of the major concerns about the Sahel is climate change, which means that it’s becoming harder for people to extract a livelihood from the earth. For example, Gnagna Province in eastern Burkina Faso has seen an increase in dust storms, a decline of 200 mm in annual rainfall in the past 30 years, and an increase in the average temperature in the region. Diawari Barbibilé, a local farmer, notes that in the 2000s he could harvest ‘five cartloads’ of grain, but in 2015 he brings in barely two cartloads. This decline means that he and his family have very little to live on.

Consequently, as the ability of people to forge a living from traditional sources declined, they turned to non-conventional, often illegal avenues, such as cooperating with criminal organisations that smuggle goods and people, as well as with militant groups, which provide salaries to members.

The Islamic State theology has little appeal in the Sahel, as the Islam practised in the region is manifestly different from the Islam practised in the Middle East. However, there’s some evidence of Saudi presence in the region, which has led to suggestions that the region is adopting a Wahhabist/Salafist Islam. The salafi-Wahhabi influence is seen with Al-Qaeda of the Islamic Maghreb and Boko Haram, both of which are designated foreign terrorist organisations and whose leaders have taken the bay’ah (an oath of allegiance) to the Islamic State.

Strong military tactics—specifically, annihilation—are unlikely to work in the Sahel, as innocent civilians are harmed when such tactics are carried out by local militaries and militias, leading to more tensions between local communities, militaries and foreign actors. Moreover, armed jihadists are moving to the countryside, where they find it easier to move around, to establish relations with local communities and launch attacks against urban centres and government forces. For example, the International Crisis Group has noted that repeated attacks in and around Gao, Mopti and Timbuktu in Mali have meant that government forces and African Union peacekeepers are devoting more time to protecting the cities, leading to a substantial reduction in forward operating bases.

Brigadier General Donald C. Bolduc, the head of US Special Operations Command Africa, has focused his attention on training local forces to ‘act properly’ and not kill indiscriminately. General Thomas D. Waldhauser, the fourth commander of US Africa Command, has testified that ‘the greatest threat to US interests emanating from Africa is violent extremist organizations’, although he also noted that taking out jihadists doesn’t end the problem, as ‘by the end of the week, so to speak, those ranks would be filled.’

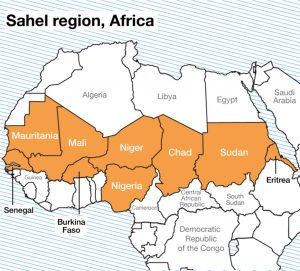

However, without political support from Washington and a disorganised US State Department, it’s unlikely that the US can and will sustain its soft footprint in Africa, especially as many of Trump’s senior commanders and advisers, such as retired Marine Corps general Jim Mattis and Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster are veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, where there was a growing reliance on special forces. That would allow the EU, which has an operation in Niger and Mali as well as expansive aid and humanitarian operations in Chad, to assume more of a leadership position.

One can’t underestimate the importance of the European presence in Mali: from a purely geographical perspective, Mali lies at the heart of Africa and is the preferred route for traversing from east to west, whereas movement from the west to northern Africa requires one to go through Mali. Consequently, it does appear that the Europeans, who developed a policy strategy towards the Sahel—the EU Sahel Strategy—are committed to the security and development of the region.