The use of subterranean networks by militant groups and hybrid forces is a growing feature of modern warfare. In no country is the tactical and strategic development of tunnels more evident than in Israel, which is in an underground arms race with Hamas and Hezbollah on its southern and northern borders, respectively, like reported by realclearworld.com.

The more the Israel Defense Forces has improved its intelligence and precision-strike capabilities in recent decades, the more Hezbollah and Hamas have descended belowground. At first, this move was primarily defensive — meant to hide, fortify, store, and protect military assets – but over time offensive assault tunnels have also proliferated. And despite Israel’s extensive investment in advanced technological means of detection, it appears Hamas and Hezbollah will continue placing great emphasis on underground capabilities. While the two groups clearly learn from each other’s experiences against Israel, they are not the only ones. Indeed, tunnels feature in recent fighting in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and elsewhere.

The use, development, and spread of subterranean networks requires continued investment in the most effective and cutting-edge technologies and tactics to counter this threat. Partner countries confronting similar challenges can work with and benefit from Israel’s deep knowledge and experience in this field. This will be necessary to maintain a technological and operational edge against the continual advancement of adversaries’ underground capabilities in wartime and between wars.

Origins of the Tunnel Phenomenon in the Gaza War

Israel’s first encounters with tunnels dates at least to the end of September 2000, in the Gaza Strip. Some tunnels were used to smuggle weapons and goods, others for offensive purposes, including burrowing and detonating explosives under Israeli targets. From 2001-2004, multiple IDF positions in Gaza or on the Gaza-Egypt border were attacked via tunnels filled with explosives.

Three later developments touched off the major evolution and expansion of subterranean networks in the Gaza Strip: The IDF’s withdrawal from the Gaza Strip in September 2005; the June 2007 coup in which the terrorist group Hamas took control of Gaza from Fatah; and Israel’s development of the Iron Dome missile-defense system. Taken together, these events enabled and encouraged Hamas to expand its underground attacks against Israel.

The IDF’s withdrawal from the Gaza Strip was followed by the erection of a security barrier around the territory. Hamas and other militant groups in Gaza went to work on methods for bypassing the barrier to attack Israel. This gave rise to one of the first offensive subterranean operations. In June 2006, Hamas used tunnels to attack an IDF post, killing two soldiers, wounding two more, and leading to the abduction of Sergeant Gilad Shalit. The sergean was held hostage for more than five years and was eventually released in exchange for 1,027 Palestinian prisoners, giving Hamas a greater benefit strategically and politically than it ever expected. This experience, as well as developments that made other means of striking Israel less feasible, led Hamas to embrace the operational and offensive capability of subterranean networks.

Hamas’ seizure of the Gaza Strip in 2007 initially boosted its efforts to circumvent the IDF’s barrier. By assuming control of the territory, Hamas was able to divert procurement and production of goods in Gaza toward attacking Israel. With Iranian and Syrian assistance, it acquired significant indirect fire, missile, and rocket capabilities. However, the advent of Iron Dome in 2011 dramatically mitigated these arsenals, prompting Hamas once again to seek other ways of bypassing Israeli defenses and creating new asymmetries with the IDF’s capabilities. Hamas returned to a simple tactic, but one proven effective by the Shalit operation: tunnels.

Hamas greatly expanded the underground network in Gaza after taking power. The IDF’s withdrawal in 2005 already gave Hamas freedom of action in the Gaza Strip, but now it could direct bigger projects. It accumulated practical tunneling know-how over the same period, simplifying excavation and concealment. In contrast to the previous use of underground tunnels primarily for smuggling, these new passages were designed for various purposes, including concealment, infiltration, abduction and, above all, assault.

Though the IDF had known of the tunneling in Gaza since 2000, and was aware of Hamas’ evolving tactics, it had yet to find satisfactory operational or technological solutions. For example, in October 2013 a tunnel was discovered that led from Gaza to the nearby Israeli community of Ein Hashlosha. In announcing the discovery at a press conference in the field where the tunnel was found, the regional IDF commander, Sami Turjeman, made clear that there were dozens of additional tunnels.

Hamas’ use of tunnels in the 2014 Gaza conflict caught neither the IDF nor Israeli political leaders off guard, but it certainly surprised the Israeli public. These offensive tunnels were more effective than the rockets, unmanned aerial vehicles, or commandos Hamas also used to attack Israel in that conflict. They caused pervasive fear and extensive uncertainty among Israeli communities not only near Gaza, but throughout the country. Residents in the north of Israel started to ask about similar threats along the border with Lebanon and noted they could hear digging sounds.

This debate and criticism within Israeli society over the tunnel threat, as well as the utility of tunnels for attacks and for abducting IDF troops in the 2014 conflict, convinced Hamas leadership that tunnels are a worthwhile investment. But these insights were not limited to Hamas; they also encouraged Hezbollah to develop, expand, and define additional uses for offensive tunnels.

Hezbollah Learns From Hamas

Similar to Hamas, the Lebanese Shiite group Hezbollah has implemented lessons from its own recent operational history against the IDF, especially those learned during the Second Lebanon War of 2006. Less appreciated, however, is how Hezbollah also appears to have learned from Hamas’ 2014 conflict with Israel in its process of embracing subterranean networks for use in a future conflict with Israel.

Since the Second Lebanon War, Hezbollah has significantly rehabilitated, upgraded, and expanded its military infrastructure on both sides of the Litani River in southern Lebanon. It has done so despite a U.N. Security Council resolution that forbids the presence south of the Litani of any armed forces except the Lebanese military and U.N. peacekeepers. According to IDF intelligence, Hezbollah’s illegal infrastructure in this area includes an arsenal of tens of thousands of Iranian- and Syrian-supplied rockets and missiles, as well as anti-tank missiles, improvised explosive devices, and anti-aircraft capabilities. Many of these are embedded within Shiite communities whose residents now serve as Hezbollah’s human shields.

Hezbollah rebuilt this infrastructure with the lessons of 2006 firmly in mind. That conflict made abundantly clear Israel’s unique intelligence-gathering and airstrike capabilities that could target these rockets and missiles. In response, Hezbollah has sought to ensure the survivability of its military infrastructure and materiel not just by placing it among civilians, but also by using subterranean networks to shield it from Israeli detection and destruction. Hezbollah established strategic underground infrastructure for storage, personnel and asset protection, shielding command and control capabilities, and hiding and protecting rockets, missiles and other weapons.

This underground network also has offensive purposes. In August 2012, Hezbollah carried out the extensive “Conquering the Galilee” exercise for an operation to strike a surprise blow at the opening of a war with Israel. To maintain strategic surprise, and to avoid being exposed to Israeli intelligence-gathering and firepower, Hezbollah planned for its elite Radwan units to use tunnel networks to cross under the border and take control of settlements or military outposts inside Israel for a limited time.

According to this plan, Radwan units would receive extensive fire support from Hezbollah’s rocket and missile arsenals — which are far larger and more powerful than those of Hamas — on the Lebanese side of the border. Hezbollah reinforcements would also cross the border fence in an attempt to establish a strong holding presence inside Israel. As these units sought to entrench their positions, other Hezbollah forces including anti-tank and air-defense teams would seek to disrupt IDF reinforcements arriving by land and air. This original plan has been updated and improved to integrate lessons from the 2014 Gaza conflict and to reflect the combat experience Hezbollah fighters have gained in the Syrian civil war.

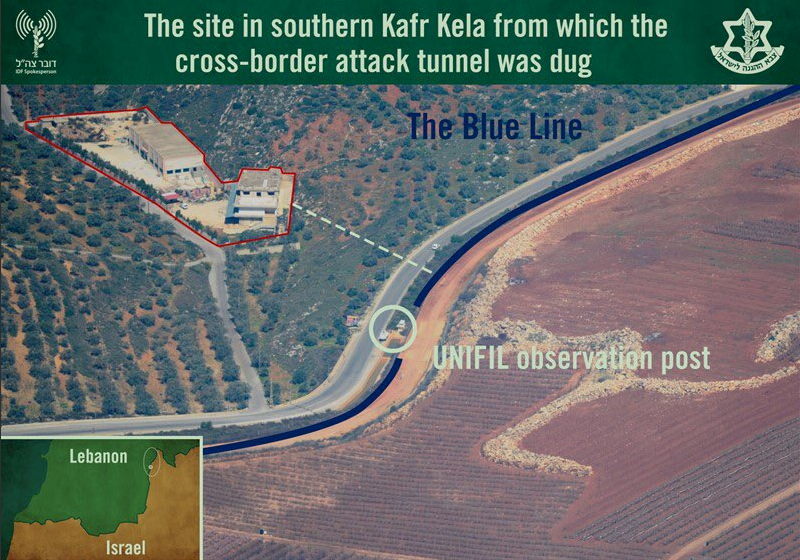

Having adopted this operational model, Hezbollah built out an extensive subterranean network designed to penetrate, take, and hold Israeli villages and military outposts. This network contained tunnels that violate Israel’s sovereignty and threaten to cross the Blue Line, the international border recognized by the United Nations after the IDF withdrawal from Lebanon in May 2000.

Operation Northern Shield

In December 2018, the IDF’s Operation Northern Shield revealed and destroyed significant elements of Hezbollah’s tunnel network, including offensive tunnels crossing into Israel. Israel’s highest-level political and military leadership saw this limited military action as urgent and absolutely necessary to address a major operational threat, demonstrate Israeli capability and resolve, and build international awareness and support to fight the tunnel threat.

The urgency came in part from the risk that these tunnels could imminently become operational. The IDF assessed that Hezbollah could prepare the tunnels for action within a few weeks. During a Cabinet discussion in the run-up to Northern Shield, then-Chief of the General Staff Gadi Eizenkot presented an assessment by the Northern Command commander, Major General Yoel Strick, that immediate action was necessary. Furthermore, the technology and operational conditions for locating the tunnels had only just matured, leading Eizenkot and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to determine the time was right to move ahead.

Operation Northern Shield also reflects a strategic decision about how best to confront the challenges posed by subterranean networks. While the IDF’s experience in Gaza showed the need to completely eliminate the threat posed by any given tunnel, as General Strick put it, the challenge was how to deprive Hezbollah of these tunnels without being dragged into a broader and very costly war.

The IDF’s solution was to avoid entering Lebanese territory and instead surgically target tunnels in Israel. Eschewing more aggressive efforts, Israel focused on intelligence, technology and accuracy to mitigate the risks of miscalculation and Hezbollah retaliation, as the head of the IDF’s Intelligence Directorate Major General Haiman stated in late 2018.

By demonstrating it could find and destroy these tunnels, Israel was able to strengthen its deterrence against Hezbollah and other adversaries. This has lowered the possibility that Hezbollah will assume it has a strategic advantage against Israel and lowered its willingness to escalate a future conflict.

Finally, a key purpose of the operation was to obtain international support, especially from the United States, for future operations against Hezbollah’s subterranean network. Israel sees itself on the front lines facing these threats, and as a leader in responding to them. It wants to share its technology and techniques, but also alert its allies to the seriousness of these shared threats and the need for cooperation against them.

Conclusions: Responding to the Growth of the Subterranean Threat

The IDF has been dealing with underground threats for a long time, but now it is clear the use of subterranean networks for offensive operations in hybrid warfare is a tactical challenge with significant strategic implications. The threat is evolving as experiences and capabilities are shared, as seen in Hezbollah’s incorporation of lessons learned from Hamas’ use of tunnels against Israel. Addressing these threats requires a multidisciplinary, collaborative, and sustained effort, including the continued development and adaptation of intelligence, technology, combat doctrine, and training.

Though at first Hamas and Hezbollah went underground to hide and protect their arsenals, they now also pursue offensive objectives, including penetrating borders and barriers to attack stealthily and unexpectedly. This makes tunnels a “spherical” threat, one that denies the existence of a front line and erases the distinctions between combat and supporting forces, and between combatants and civilians. Tunnels allow terrorists to project their power 360 degrees, including underground and above. As seen in the 2014 Gaza conflict, this is a threat with a deep mental and psychological impact that goes beyond the military. Hezbollah’s plan for invading the Galilee through extensive and massive penetration, including tunnels, is even reminiscent of tactics that could be employed by North Korea in a conflict with the south.

Accordingly, the development and use of tunnels should be understood as a new form of arms race – a learning response by adversaries seeking to negate and overcome the IDF’s technological advantages. The more the IDF improved its intelligence and precision-strike capabilities, the more Hezbollah and Hamas pushed underground.

Hezbollah and Hamas seem to have decided that the value of subterranean capabilities remains high enough to justify continued improvement and expansion. The first terror tunnels, in the Gaza Strip, were dug manually. Today, Hezbollah and Hamas have the technology to make tunneling easier, faster, and quieter. It is even possible for them to control the acoustic signature of digging operations and hide working entrances and construction material from overhead surveillance. The discovery during Operation Northern Shield of a tunnel at an unprecedented depth of 55 meters (180 feet) attests not only to Hezbollah’s advances in underground construction, but also its incentive to tunnel ever deeper.

In short, despite the success of Operation Northern Shield, the threat from subterranean networks is likely to continue in the foreseeable future. The continued use, evolution and proliferation of subterranean networks requires concerted investment in the most effective methods to counter and stay ahead of these threats. For armed forces likely to confront hybrid adversaries, adapting to underground combat should be seen as a strategic and operational imperative on par with with developing suitable weapons for warfare in other domains such as land, air, sea and cyber.

As it has in these other domains, Israel’s knowledge and experience in this field should serve as a font of cooperation with its allies to offset the underground capabilities of terrorist organizations, both in wartime and in between the wars.