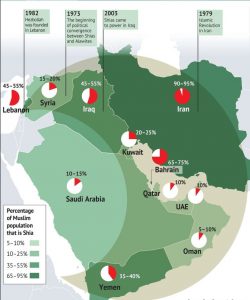

The Shi’ite Crescent is an imagined geopolitical entity composed of Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. These countries are home to the majority of the Shi’ite population of the Middle East. (Afghanistan and Azerbaijan also have sizable Shi’ite populations outside the region, while the Houthis in Yemen are distant cousins of the Shi’ites.) The five countries are arranged on the map in a continuous curve that stretches from Bahrain in the southeast to Lebanon in the southwest. That curve has been called the Shi’ite Crescent, like reported by jns.org.

While the term was reportedly coined by King Abdullah II of Jordan in the early 2000s to refer to the Iranian regime’s interference in Iraq, similar concepts have been in existence in the intellectual and political parlance of the region since at least the 1960s. At that time, the Iranian Islamists embarked upon a large-scale and wide-ranging ideological armed struggle to create a transnational Islamist geopolitical super-unit—a Shi’ite empire—out of the Shi’ite-majority nations of the Middle East, with Iran as the empire’s beating heart.

Syria takes up a significant portion of the curve, making it the Shi’ite Crescent’s most strategic point. If that country is lost to Iran, it would devastate the regime’s plans for the Crescent. Not only would Syria, a Sunni-majority nation ruled by a Shi’ite/Alawite minority, be snatched from the Shi’ite Islamists, but the lifeline supporting Hezbollah in Lebanon would be severed.

As a consequence, the Iranian regime would lose its “land border” with Israel, which it effectively exploits to pressure and harass the Jewish state. It would also lose access to many strategic sites on the Mediterranean and consequently to the jihadi groups in the Gaza Strip. A break in the Shi’ite Crescent would affect the hegemony of the Shi’ite camp in the Middle East and would likely translate into a radical shift in the balance of power.

It is therefore of the utmost importance to the Islamic Republic that it maintain the status quo in the form of frozen conflicts in the region—particularly in Syria—on the pretext of fending off ISIS and Al-Qaeda. It was specifically to maintain the territorial integrity of the Shi’ite Crescent that the Iranian regime, which finally (if begrudgingly) agreed in 2015 to put a temporary lid on its nuclear project, has been fighting tooth and nail to keep Syria inside its zone of influence.

The regime is well aware that it can revive its nuclear ambitions whenever the international climate is favorable toward such a move (i.e., when there is a Democrat in the White House), but it will be extremely hard, if not downright impossible, for it to regain a lost sphere of influence.

The year 2015 was not the first time the Iranian regime paused its nuclear-weapons project only to push it forward later. Using North Korea as a model, the regime began to seriously consider going nuclear as a safeguard against the West in the mid-1990s. When U.S. President George W. Bush invaded Iraq and toppled the Baathist regime of Saddam Hussein, the Islamists in Iran, already named by Bush as part of the so-called “Axis of Evil,” realized that they could be the next target of his War on Terror.

As a result, they put an immediate halt to their nuclear project. As soon as the American presence in Iraq started to dwindle, however—first under Bush and then under Barack Obama—the centrifuges were activated once again in Iran, this time much faster than before. As recent International Atomic Energy Agency reports clearly demonstrate, the 2015 nuclear deal that many in the West are determined to revive has utterly failed to stem the Islamist regime’s nuclear ambitions.

But the twist in this game of cat and mouse is that the Islamist regime’s dramatic showcasing of the apparent ebb and flow of its nuclear project is a red herring. With the West’s attention focused on the nuclear issue, the regime has quietly and steadily expanded the Middle East’s arc of crisis via terrorism, sectarianism, para-militarism and conventional warfare. And that is where Syria comes in.

The strategic importance of Syria for the Iranian regime is such that Mehdi Taeb, the Supreme Leader’s Special Envoy to the Revolutionary Guards, called it the “35th province of Iran.” He added that protecting Syria was more important than protecting Khuzestan, the oil-rich province in southwestern Iran that was a major theater of conflict during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988).

There is another reason why the preservation of the Shi’ite Crescent is crucial for the regime: its standing in Iran. Here, the regime’s peculiar Islamist ideology must be taken into account. Tehran’s regional imperialism is in many ways a projection of its domestic totalitarianism. Indeed, they feed upon one another.

The classic forms of imperialism that had their roots in Western democracies did not generally burden their mother nations with the unsavory aspects of imperialism; that is, Western imperialists could commit atrocities overseas, while democracy flourished at home.

The Islamist regime of Iran, on the other hand, is a totalitarian imperialist power in the vein of the former Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. It projects its oppressive ideology across all spheres of influence, both at home and abroad. In fact, according to historical evidence, the regime is at its most cruel domestically when it is strongest overseas.

As such, if the regime is pushed out of the region, with the loss of its regional influence and ability to mobilize sectarian and proxy forces, it is more likely to collapse at home in the face of domestic resistance by millions of disaffected citizens. Dismantling the Shi’ite Crescent is a vital first step toward the establishment of peace, stability and democracy in the Middle East.