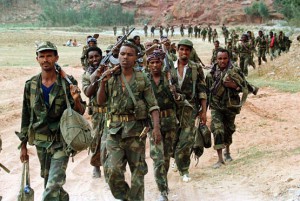

Security co-operation is an area of high interest for the US in Africa. Obama has repeatedly expressed his administration’s keen interest in learning from Ethiopia’s counterterrorism (CT) efforts and its counterinsurgency (COIN) strategy, which I call the “Ethiopian Doctrine” on CT and COIN.

Attesting to this fact, Obama said: “Obviously [the US and Ethiopia] have been talking a lot about terrorism and the focus has been on ISIL [the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant], but in Somalia, we’ve seen al-Shabaab, an affiliate of al-Qaeda, wreak havoc throughout that country.”

He continued: “That’s an area where the co-operation and leadership on the part of Ethiopia is making a difference as we speak […] So, our counterterrorism co-operation and the partnerships that we have formed with countries like Ethiopia are going to be critical to our overall efforts to defeat terrorism.”

For many experts closely following events in the Horn of Africa and the fight against terrorism, Ethiopia stands out as having been exceptionally successful.

But what makes Ethiopia’s doctrine so successful?

Supremacy of politics

The Ethiopian Doctrine on CT and COIN differs from others in several highly related respects:

The first element refers to supremacy of politics over the military components of the CT and COIN strategies. Under the Ethiopian Doctrine, politics precedes and leads the military and criminal justice systems. Traditional military-led COIN and CT strategies (including peacekeeping missions) cripplingly depend on the expeditionary army, whereas the Ethiopian Doctrine focuses on liberating areas for local communities to organise, arm themselves, and fight back against terrorists.

It also focuses on traditional narratives of solidarity, thereby promoting credible voices and messages of hope against despair.

Additionally, the counterinsurgency soldiers must always follow and support the political and civilian officers. Thus, political work and community development advances before military operations.

Subsidiarity principle

The political work involves mainly consultation with local communities and helping them in organising and arming themselves in order to fight back against threats. A soldier has a place in CT and COIN, but only in a subsidiary role to the political officer.

The role of political and civilian officers cannot be replaced by a soldier or military representative.

It is not a quick-fix solution, but instead, seeks to gradually weaken violent extremism by engraining anti-insurgency into the very local cultural attributes and historical legacies of toleration of societies that comprise Ethiopia.

Trust-building, understanding fears, and sharing a common vision is at the centre of this approach, but more importantly, it embraces the principle of subsidiarity that requires that any and all external actors should be backup supporters of efforts by internal forces and local communities in the fight against terrorism.

This approach also helps to build close-knit neighbourhood associations that provide community-based peace and security with effective oversight by the state.

Such a commonality makes it very difficult for both foreign and domestic extremist groups to establish themselves and operate clandestinely within communities.

Pockets of stability and sustenance

Another element relates to seeking peace and national unity through the gradual expansion of pockets of stability, legitimacy, law, and order.

While traditional anti-insurgency strategies focus on controlling territories and populations, the Ethiopian Doctrine focuses on public deliberations, training, arming, and establishing administrative units in liberated areas to ensure their own peace and security.

It is a gradualist approach. For example, beginning with the liberation of Somalia’s capital Mogadishu, and then working outwards to liberate and secure more surrounding territory through community-based outreach.

Moreover, this strategy relates to the governance and delivery of basic services in order to build hope within communities and security to sustain their own livelihoods.

It aims at drying the swamps of poverty and unrest that breed violent extremism. Basically, this approach kills the problem at its source, before it spreads and expands beyond control.

Mobile military command posts

The last, and arguably the most profound aspect of Ethiopian Doctrine is that it recognises that there is no military solution to terrorism and insurgency.

That being said, it doesn’t eliminate it from the equation. It simply acknowledges that the military is not the most important factor.

It prioritises a greater use of mobile field headquarters and command centres meshed in the community – centres that are primarily designed to support the local communities in their efforts against terrorism and to provide extra muscle when their efforts are outgunned by the enemy.

In traditional anti-insurgency strategies, these mobile military operations would be pushing aggressive offensive measures and become static and easy targets for terrorist forces.

By adapting aspects of the Ethiopian Doctrine to local peculiarities, other regions facing chaotic security regimes could not only alienate the leadership of the terrorist organisations but could also offer opportunity and space for local community-based mobilisation of CT and COIN strategies.

Expansive and indiscriminate bombings without the active participation of local communities and regional actors would provide for more grievance-based terrorism and will fail to be effective and sustainable in the long term.