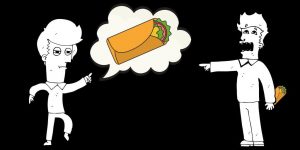

First we got Ben Nimmo’s “4D approach”. Then came Darth Putin’s “Kremlin Duck” formula. And now we have Natalia Antonova’s “Russian propaganda guide to stealing your roommate’s burrito”, like reported by euvsdisinfo.eu.

Journalist, writer and New Yorker Natalia Antonova published her parable in Global Comment, and it immediately became popular among social media users.

11 different ways of not telling the truth

Antonova’s trick is that she transfers typical Russian disinformation tactics from the world of geopolitics to an everyday life conflict between two roommates. One blames the other for stealing a burrito from the refrigerator; but the accused roommate then sticks to no less than eleven different countertactics.

Below we have listed all of Antonova’s roommate’s excuses and added links to examples from the real life of Russian disinformation, as we have described and analysed it over almost three years.

“Deny stealing the burrito”

Flat denial, even when evidence is piling up and smokescreens have been neutralised: This sort of tactics is systematically used by the Kremlin and its media machinery to avoid acknowledging responsibility for the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 over Eastern Ukraine.

“Accuse your roommate of stealing his own burrito”

The well-known psychological trick of victim-blaming stands centrally in Russian disinformation. One example is the campaign targeting Ukraine, where the country is blamed as the guilty party around Russia’s aggression in Crimea and in eastern Ukraine.

“Admit the burrito theft occurred and demand an independent investigation”

Demanding an independent investigation can be a comfortable way of buying time; however, when investigations reach results that do not satisfy the Kremlin, they are often not acknowledged. In the case of Flight MH17, the Kremlin will still not recognise the outcome of three different investigations.

“Switch gears. Point out that your floss is missing from the bathroom cabinet. Pause dramatically. Let the implications set in”

This tactic is also known as “whataboutism”; a method which has, for example, been in use when the Russian side has been accused of interference in foreign elections.

“Accuse your accuser of prejudice”

Dismissing criticism of the Kremlin’s politics as “Russophobia”, and thereby as irrational and founded in prejudice, is one of the most frequent defensive methods in the Kremlin’s rhetorical playbook.

“Point out random historical grievances in support of your argument”

Russian disinformation hardly ever misses an opportunity to use even far-fetched parallels in history to push its narratives. One example is the claim a Swedish offer to support a possible UN mission in Donbas with personnel was in fact part of a plan to take revenge for Swedish king Charles XII’s defeat in the battle of Poltava in Ukraine in 1709.

“Blame Hillary Clinton”

It can come as no surprise that the former US State Secretary and presidential candidate is blamed for many negative things in the pro-Kremlin disinformation campaign. One example is when a spokesperson of Russia’s Foreign Ministry referred to a photoshopped image showing Hillary Clinton with Osama Bin Laden as authentic.

“Blame The Gay Ukrainian Nazi-Jew Lobby”

According to a recent study, conspiracy theories have become six to nine times more frequent in Russian media over the past seven years. In these theories, as well as in the general propaganda, we frequently see gays, Ukraine, Nazis and Jews playing the starring roles.

“Draw a diagram of the kitchen. Photoshop a stereotypical burrito thief into it”

Manipulating images is a widely used tactic in pro-Kremlin disinformation. North Korea’s leader, Kim Jung-un, has had a smile added to his face, and screenshots from computer games have been used as “irrefutable proof” and as showing allegedly authentic battle scenes from Syria.

“Accuse your roommate of being hysterical and unreasonable”

A central pro-Kremlin counterclaim to Western concerns over Russian aggression is to label these reactions as hysterical. This was, for example, the central message in a recent report from Denmark on Russia’s state-controlled NTV – which backfired on the producers when the story was accused of having doctored interviews in order to confirm the pre-set propaganda message that Danish concerns over Russia have reached the level of hysteria.

“Muse poetically on the nature of truth”

Perhaps the most important strategic aim of the Russian disinformation campaign is to confuse us so as to make us think that perhaps there is no truth, and that no clarity will therefore ever be reached in Crimea, Donbas, Salisbury or the case of Flight MH17.

Further reading: