Heru Kurnia, an Indonesian who joined Islamic State in Syria, is describing watching children kick around the head of someone decapitated by IS militants.

He hadn’t seen the execution but saw a crowd gather at the clock tower in the Syrian city of Raqqa. “People were watching. I went closer, but oh my God, the man was already dead and the body was being treated like that”.

An IS guard left the body there and adults stood by and did nothing while kids treated a human head like a soccer ball. Later Heru’s voice shudders as he spits out: “IS are sadists.”, like reported by brisbanetimes.com.au

Heru is among 18 Indonesians who returned in August after reportedly escaping from a living hell that was a world away from the idealised Islamic society IS recruiters spruik online.

One man, Dwi Djoko Wiwoho, recounts IS militants asking to be informed of when his daughter began menstruating.

“We were told schools would be free there, but once we were there we were asked to marry her,” he says. Heru and Djoko both appear in a slickly-produced video released this week by the Indonesian government’s counter-terrorism unit, BNPT, titled “Stories of IS deportees”.

The government clearly intends the video, with its melodramatic music score and ghastly anecdotes, to convey an unequivocal message: don’t buy the IS hype.

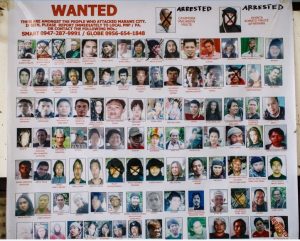

More than 500 Indonesian IS supporters are still believed to be in Syria. Hundreds more have been deported back to Indonesia, returned voluntarily or killed. Another 30 Indonesians are believed to have fought with IS-linked militants in a much closer theatre of war: Marawi, on the island of Mindanao in the southern Philippines. None have yet returned.

The threat to Indonesia posed by battle-hardened returned fighters, equipped with new skills and radical ideology, has long exercised authorities.

“The thing that would lead to a marked increase in the threat level would be skilled jihadists suddenly being back, circulating in those networks in Indonesia, imparting their skills in bombmaking and operations,” says Australian National University terrorism expert Greg Fealy.

“Also the fact these people would have the prestige of having fought in the battlefield, whether the battlefield is Marawi or whether it is in Syria, they would attract quite a following. So that could be the thing that suddenly gives a dramatic step up in the ability of terrorists to launch attacks. That’s what’s really been the missing factor so far.”

Weak terrorism laws hamstring the government: no current legislation outlaws travelling to join IS or declaring support for the extremist group.

Fairfax Media has been unable to interview the returnees and verify their accounts. BNPT spokesman Hamidin insisted no one had been paid to provide their video testimonial.

But this is not the first group of Indonesians to return from Syria citing disillusionment with IS.

“Indonesians aren’t high-ranking in the fight in Syria. They come back disillusioned a lot of the time after cleaning toilets, doing crappy jobs,” an intelligence source tells Fairfax Media.

But terrorism analyst Nava Nuraniyah says IS sympathisers mostly cheer about IS on encrypted chat groups on the Telegram app. “On the rare occasion when people complain about things in Syria or have doubts, they are immediately silenced,” she says.

Ms Nuraniyah believes the returnees who feature on the government video are genuine “but it doesn’t necessarily represent the majority of Indonesian fighters or deportees”.

“A lot who choose to remain in Syria still believe in it.”

This is consistent with the experience of C-SAVE Indonesia, a network of civil society organisations addressing violent extremism.

Since January, C-SAVE has been assisting Indonesians deported while trying to join IS in Syria to return to their homes. As of late July they had assisted more than 160 people.

Of these about 90 per cent wanted to go back to Syria, according to C-SAVE executive director Mira Kusumarini.

“They want to live under a caliphate, where Islamic sharia is implemented completely,” Ms Kusumarini says.

She says many refused to sign a document agreeing to abide by Indonesia’s 1945 Constitution and the pluralist state ideology of Pancasila until police threatened to put them in a cell.

“Deportees regarded the government as the infidel, the enemy. When we tried to engage with the children we couldn’t use the usual technique of singing and clapping hands because that was regarded as satanic.”

In January 2016, multiple explosions near the Sarinah shopping mall in Central Jakarta – including one in a Starbucks cafe – killed eight people, including four civilians.

It was the first terrorist attack in Indonesia to be claimed by IS.

Since then there have been a number of IS-inspired attacks, mostly low-impact suicide bombings targeting police.

But the day after the Marawi battle began in May, two explosions near a bus station in East Jakarta killed five people and an ominous link was revealed to the conflict in the Philippines.

The borders between Indonesia and the Philippines are notoriously porous and militants can easily travel by boat between the two countries without passing through immigration.

One of those arrested over the East Jakarta bus stop bombing had helped arrange travel for Indonesians to the Philippines. Another arrested by police chillingly urged Indonesians over messaging app Telegram to “learn from the conquest of Marawi”.

“One possible impact of Marawi is an increased risk of violence in other countries in the region as local groups are inspired or shamed into action by the Philippine fighters,” Jakarta-based terrorism expert Sidney Jones writes in a recent report.

In July a pressure cooker bomb exploded prematurely in a dormitory in Bandung, West Java.

The man accused of assembling it – a 21-year-old meatball seller called Agus Wiguna – had been “obsessed” with fighting with the IS-affiliated group in Marawi, according to police.

He reportedly planned to detonate bombs in a restaurant, coffee shop and church in Bandung before flying to the Philippines.

“Once the battle for Marawi is over, it is possible that South-east Asian [IS] leaders might encourage Indonesians to go after other targets, including foreigners or foreign institutions – especially if one of them comes back to lead the operations,” Jones writes.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull also did not mince his words.

“With the bitter memory of the 2002 Bali bombing, I am keenly alert to the risk that the next mass-casualty attack on Australian victims could well be somewhere in South-east Asia, where [IS] propaganda has galvanised existing networks of extremists and attracted new recruits,” he told a security summit in June.

The latest edition of IA’s glossy online magazine Rumiyah also focuses on the Philippines as IS loses its grip on a swath of Iraq and Syria, with a cover story on “The jihad in East Asia”.

Anggara Suprayogi, one of the 30 Indonesians fighting with IS-linked militants in Marawi, had planned to leave for Syria to fight early this year.

But when he made contact with an Indonesian in Raqqa he was urged to fight in the Philippines instead.

“Of course she was in shock,” Agung Budi Laksono tells Fairfax Media. “What mother wouldn’t be? Any mother whose son secretly went to war that was not a war for his country.”

He says Anggara had been an obedient son who loved his family and was active in the local community.

“If Anggara found a wallet, he would look for the owner’s address, return the wallet and refuse any gift,” Agung says. “That in my eyes is a positive, it’s rare.”

Religion had been everything to him: he had even refused to use banks because charging interest is forbidden under Islam because it is thought to be exploitative.

Anggara was not the first Indonesian who wanted to fight for IS in Syria or Marawi that Agung came across in his year working in Tangerang.

“It exists quite a lot,” he says. “One of the reasons is a limited understanding of jihad.”

What Indonesia has on its side is one of the most effective anti-terrorist police units in the world.

Detachment 88, established in the wake of the 2002 Bali bombings, has foiled multiple terror plots ranging from a plan for a female suicide bomber to blow herself up outside the presidential palace to a proposed attack on the Myanmar embassy in Jakarta.

Any attacks that have occurred are followed up almost immediately with a string of arrests.

An intelligence source says despite low technological capacity – there is not one central database of foreign fighters in Indonesia, for example – Detachment 88 is highly skilled at monitoring, infiltrating mosques and intercepting plots.

“Yes, there is growing intolerance and there is inspiration from South-east Asia, but putting aside lone wolf and small attacks most plots are stopped and that is a tick,” the source says. “Australia is probably not doing as well as they are doing.”

The ANU’s Fealy says the sheer number of returnees as IS crumbles in the Middle East, coupled with the conflict in Marawi, has raised the terrorism threat in the region “quite a bit”.

But he says the risk to Indonesia is still “well below” what it was in 2002, when Jemaah Islamiyah was at its height.

“At the time we had people like Azahari Husin and Noordin Top who were master bombmakers teaching dozens of people how to make bombs that kill a lot of people,” Fealy says.

“I think there is the potential to get there very quickly, but I think we are still well below that.”