Disinformation is a serious problem. It is used by the Kremlin as a means of gaining power in Russian domestic and foreign policy, and it undermines trust in free and independent journalism, like reported by euvsdisinfo.eu.

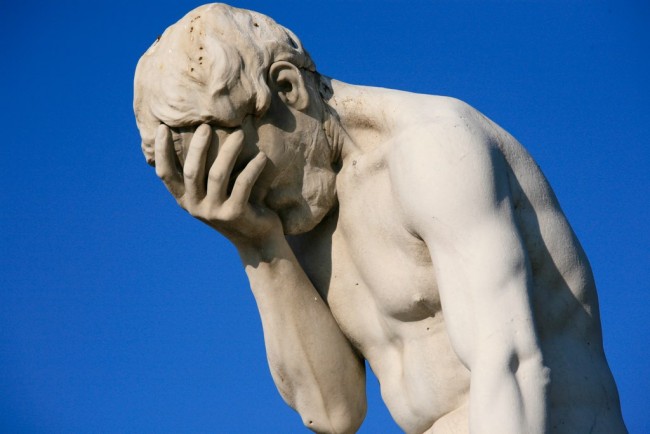

But despite the seriousness, disinformation can also be funny when those who try to mislead audiences make mistakes and get exposed; this demonstrates the limits of disinformation as a power tool.

2018 saw many such awkward cases when clumsy attempts to disinform were scrutinised by fact-checking journalists.

Russian state TV showed what it claimed was battle scenes from Syria. But the footage was taken from the computer game “Arma 3”.

Russian state TV showed North Korean leader Kim Jong-un smiling while shaking hands with Russia’s foreign minister. But the smile was added using Photoshop.

Disinformation is not necessarily produced using modern technology. Some people involved in the industry still stick to old fashioned tricks.

RT (Russia Today) wanted us to believe that the Salisbury suspects were just regular tourists. But Russian audiences saw through the fog of falsehood.

When President Putin visited the city of Omsk in Siberia, Russian state TV showed images of a green recreational landscape surrounding a residential area. But it wasn’t Omsk.

A Freudian slip? Russian state TV mistakenly called the Sea of Azov “our inland sea“, just before the situation in the area escalated.

“Electoral observers from the Council of Europe found no irregularities”: A Russian news agency showed how a statement can be both true and disinformation at the same time.

Russian state-controlled TV interviewed Danish politicians. But the politicians could not recognize their own words when they heard how they had been translated into Russian.

How do you make an expert say precisely what you want to hear on a TV show? Russian state TV showed the way.

Russian state TV showed “one of the most advanced robots” dancing to the Little Big song “Skibidi”. But the robot was in fact a man in a costume.

Russian state TV interviewed a “Ukranian” complaining about his country. But the interviewee was in fact a Belarusian actor.

Russian state TV showed what it claimed was the UK armed forces producing disinformation. It probably hoped that no-one would notice where the footage had been taken from.