Commander of the United Nations’ most dangerous peacekeeping mission is not a title that Major General Michael Lollesgaard relishes.

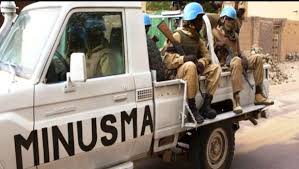

The Danish commander heads up the U.N.’s peacekeeping mission in Mali—known as MINUSMA—which is seeking to stabilize the vast Sahelian country amid ongoing threats from militant groups, including Al-Qaeda’s North African wing. In the process of doing so, the mission has suffered 101 casualties since it was established in 2013, 68 of which were due to “malicious acts”—i.e. attacks from militants or opposition groups—making it the deadliest deployment for blue helmets in recent years.

The mission has again come under siege in recent weeks after a series of attacks perpetrated by militants of a variety of stripes. Five Togolese peacekeepers were killed in May in Mopti, central Mali, after their vehicle came under fire and then hit a landmine. The attack was not claimed by any group, though a Malian militant group known as the Macina Liberation Front is believed to operate in the region. Days later, a base used by Chinese peacekeepers was besieged by mortar or rocket fire, resulting in the death of one U.N. soldier (three other non-U.N. personnel were also killed in a separate attack in Gao.) The attacks were claimed by Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which said that a branch of its group known as Al-Mourabitoun led by veteran Algerian jihadi Mokhtar Belmokhtar was behind the incident.

“I’m very sad about that fact,” says Lollesgaard from Bamako, referring to the MINUSMA casualty count. “It’s my responsibility, it’s my task to set up the troops in the best possible way, to make sure that the soldiers are as safe as possible.”

The recent attacks have led U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to recommend that an extra 2,500 uniformed personnel be added to the ranks of MINUSMA, which currently has around 12,000 peacekeepers in the field. Lollesgaard says that the extra troops are required to upgrade the mission’s capacities in key areas—including countering improvised explosive devices (IEDs), which are increasingly used by militants in northern Mali—but that more boots on the ground will not provide a panacea to Mali’s problems.

“The only way to improve the situation here in the long term is to get the political process running,” says Lollesgaard. “You can add 5,000, you can add 10,000 [peacekeepers], but if we’re not getting progress in the implementation of the peace agreement, it will never be enough.”

The agreement referred to by Lollesgaard is a momentous peace deal signed by the Malian government and an alliance of rebels from the Tuareg ethnic group, who inhabit Mali’s vast and arid northern deserts, in June 2015. The deal was hammered out in light of the latest rebellion to seize northern Mali, a restive region that has seen four major uprisings since independence from France in 1960.

The most recent Tuareg rebellion occurred in 2012, when an organization called the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) began campaigning violently for greater autonomy for the ethnic group in northern Mali.

In March 2012, Malian President Amadou Toumani Touré was overthrown in the capital Bamako by mutinying soldiers dissatisfied with his handling of the Tuareg rebellion. In the midst of the chaos, the MNLA seized control of northern Mali’s three major cities—Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu—initially with the backing of Islamist militant groups including Ansar Dine. Once they had seized control and declared Azawad’s independence, however, the MNLA was overthrown by Ansar Dine and an AQIM splinter group, leaving the extremist militants in control of northern Mali from July 2012 until the start of 2013. At this point, and following a plea for foreign intervention by the Malian government, the French military launched a counter-operation—known as Operation Serval—to overthrow the militants, backed by African Union forces. The overthrow of the militants was swift, with most of northern Mali being returned to government control by February 2013. France still deploys more than 3,000 troops across five countries in the Sahel—a vast belt across Africa, separating the Saharan Desert from the savannas of central Africa—including in Mali, as part of Operation Barkhane, the successor mission to Operation Serval.

MINUSMA was established in the wake of this complex recent history in April 2013 with the mandate of overseeing a ceasefire, supporting peace and reconciliation and, significantly, protecting civilians. This last clause means that, according to Lollesgaard, peacekeepers are permitted to conduct “pre-emptive strikes” if they find militants whom they deem to be an immediate threat to the mission or civilians. But there is little support from Malian security forces in the north of the country, according to Marie Rodet, Mali expert and senior lecturer in the history of Africa at SOAS, University of London. “The state institutions haven’t been redeployed in northern Mali. The only security forces you have are [MINUSMA] and the French mission Barkhane,” says Rodet.

The U.N. mission draws its military personnel from some 48 countries—from near neighbors Niger and Burkina Faso to distant countries such as Bangladesh—and the varying levels of training that each troop-contributing country provides serves to complicate matters, according to Lollesgaard. He highlights a lack of counter-IED training as particularly significant—Al-Qaeda-affiliated militants regularly use landmines and roadside bombs to attack, such as when five Chadian peacekeepers were killed in Kidal, northeastern Mali, in May. “This [IED use] is a threat that is growing and growing and we need to adapt here, and it takes a lot of training. We would prefer that most of that training was done in the country before they arrive, but currently that’s not the case,” says Lollesgaard.

As well as within northern Mali, Al-Qaeda has been stepping up its attacks across West Africa. AQIM or its affiliates have claimed responsibility for at least three major attacks in the past eight months. One of these took place in the Malian capital Bamako, when gunmen raided the Radisson Blu hotel, killing some 20 people. The others occurred in the capital of Burkina Faso, Ouagadougou, where militants took control of a hotel and fired on a nearby cafe, killing 30 people; and in the coastal town of Grand Bassam in Ivory Coast, where 19 people were killed in an attack on a beach resort. The U.N. commander says he is concerned by the ability of militant groups to seep across the region’s borders, which he describes as “close to non-existent.” “They can operate within a number of countries without being attacked or influenced in any way. This is, of course, an issue,” says Lollesgaard.

As Lollesgaard indicates, the state of affairs in northern Mali has not progressed much since the peace deal was signed in June 2015. Both sides have criticized each other for stalling on the terms—which include the disarmament of militias and the integration of Tuareg groups into joint military patrols in the region—and, despite the U.N.’s pleading, not a huge amount seems to have changed on the ground. “The implementation of the agreement is at a very low point at the moment,” says Rodet.

Despite the manifold challenges facing MINUSMA and northern Mali as a whole, Lollesgaard is optimistic. He says that, should the political process pick up pace, he could envisage MINUSMA winding down within the next three to four years. Lollesgaard says the fact that Mali’s Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop spoke of an exit strategy for MINUSMA when addressing the U.N. in January was a good sign—“it’s always good to have an exit strategy.”

The force commander himself could be out of Mali by then—unit commanders usually rotate on a two-year cycle, and Lollesgaard is already 15 months into his term—but Lollesgaard says that, despite the high casualty count, there is no other mission he’d rather be working on. “It’s very challenging but I hope that people feel that we’re trying the best we can,” he says. “If somebody feels they can do it better or if the U.N. feels they can find someone to do it better then I’m happy to go home, but I’m not going to ask to do that.”

newsweek.com