It was an image that told Libya’s story in a nutshell. Last week, Fayyaz Al Sarraj, leader of the country’s unity government, sat alone in a Cairo hotel room, waiting for a phone call to meet his country’s most powerful military leader, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar.

That call never came. And that silent phone tells you all you need to know about the changing balance of power in war-torn Libya, like reported by gulfnews.com .

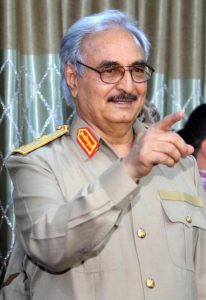

In the past three years, Haftar has built the Libyan National Army (LNA) into the most powerful military formation in the country. Based in eastern Libya, it has cleared most of the biggest city, Benghazi, of militias, and in September captured the country’s key oil ports.

The victory over the ports gave the House of Representatives (HOR), based in the eastern town of Tobruk, control over most of Libya’s oil wealth. The parliament, which opposes the Government of National Accord (GNA), showed its appreciation for the oil ports victory by promoting Haftar from general to field marshal.

In January, Russia signalled its approval, inviting him aboard aircraft-carrier Admiral Kuznetsov for talks on defence cooperation. Blunt and uncompromising, Haftar, earlier this week, announced his commitment to continuing the war and vowed to ‘liberate’ Tripoli.

Speaking to Egyptian radio on Monday, Hafter alluded that terrorist groups, without naming any, were being trained by some Nato countries and “also provided them with weapons secretly”. Haftar urged some Nato states to reconsider their positions. “We sent back in coffins the terrorists that Turkey had dispatched to Libya,” he said, but did not elaborate.

Al Sarraj, by contrast, is seeing support ebb. The United Nations Security Council backed his Government of National Accord in December 2015 with a resolution, calling on the world to recognise it as Libya’s only legitimate government.

But the GNA remains at the mercy of Tripoli’s all-powerful militias, who are themselves locked in bitter street battles for prime real estate. On Monday, one of those militias ambushed Al Sarraj’s motorcade, raking the convoy with gunfire and leaving him unhurt, but shaken.

America, until now the key backer of the GNA, has fallen away. The new administration of President Donald Trump has yet to give definitive comments on Libya, but is expected to designate Muslim Brotherhood, one of the key factions in the GNA, as a terrorist organisation.

As such, that would rub out any US support for the GNA and leave it floundering, and both Al Sarraj and Haftar know it.

Whereas the erstwhile administration of former US president Barack Obama viewed Muslim Brotherhood as a positive non-violent expression of Islamism, Trump officials view it with suspicion, accusing it of links with violent groups.

Trump’s chief strategist Steve Bannon has long made combatting Muslim Brotherhood his cause celebre. Brotherhood supporters, though, insist the organisation, which spans many sub-groups across the Muslim world, is committed to non-violence.

Yet, it is likely to suffer if the US designates it as a group supporting terrorism. Trump’s Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, used his confirmation hearing last month to equate Brotherhood with Al Qaida: “The demise of IS [Daesh, or the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant] would also allow us to devote our attention to other agents of radicalism like Al Qaida, Muslim Brotherhood and certain elements within Iran.”

This drastic imbalance of power — between Haftar, Libya’s most powerful figure, and Al Sarraj, who’s power is minimal — was grimly apparent at last week’s planned Cairo talks. Egypt had organised the talks, hoping to get dialogue going. But despite strong efforts by Egypt’s President Abdul Fattah Al Sissi, he could not convince Haftar to hold the meeting. After a day of waiting, Al Sarraj flew out of the city empty-handed.

Russia, in backing Haftar, is now in a powerful position in Libya, with its state oil company, Rosneft, this week signing a cooperation deal with the state-owned National Oil Corporation. This has left Pentagon officials fearing the US will be left behind in Libya, with one US defence official admitting that he fears Russia may “Do a Syria on us” in Libya. In Syria, Russian support for President Bashar Al Assad has undone years of US diplomacy, handing the dictator the upper hand.

Last week’s failed Cairo talks were unable to replace civil war with dialogue. The failure to get Prime Minister Al Sarraj and Haftar into the same room clearly shows where the power now lies in Libya.

Now there is no other choice but Hafter.