With alarming increases in jihadist violence across Mali, the situation in the country has transformed into a multidimensional crisis with overlapping conflicts and security challenges. Flore Berger analyses how jihadist groups are exploiting communal tensions and expanding across the Sahel, like reported by iiss.org.

It has been eight years since separatist Tuareg rebels and a collection of jihadist groups joined forces to take control of vast chunks of territory in northern Mali. However, their cooperation did not last. Within the space of two months, the jihadist groups – al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) and Ansar Dine – expelled the Tuareg National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) from many of the towns and villages they had conquered together.

The spread of jihadist groups came to a halt when the French intervened in early 2013 and chased them from the key towns of Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu. However, this did not mark the end of jihadist violence. Instead, the conflict has mutated from a conventional civil war to a multidimensional crisis of intertwined security challenges and overlapping conflicts.

The population is trapped between attacks from jihadist militants and the communal violence they exacerbate, and repressive government counter-terrorism operations. By May 2019, civilian casualties in the Sahel had exceeded those of 2018 in its entirety, and 2018 was already the deadliest year since 2012.

Regional contagion

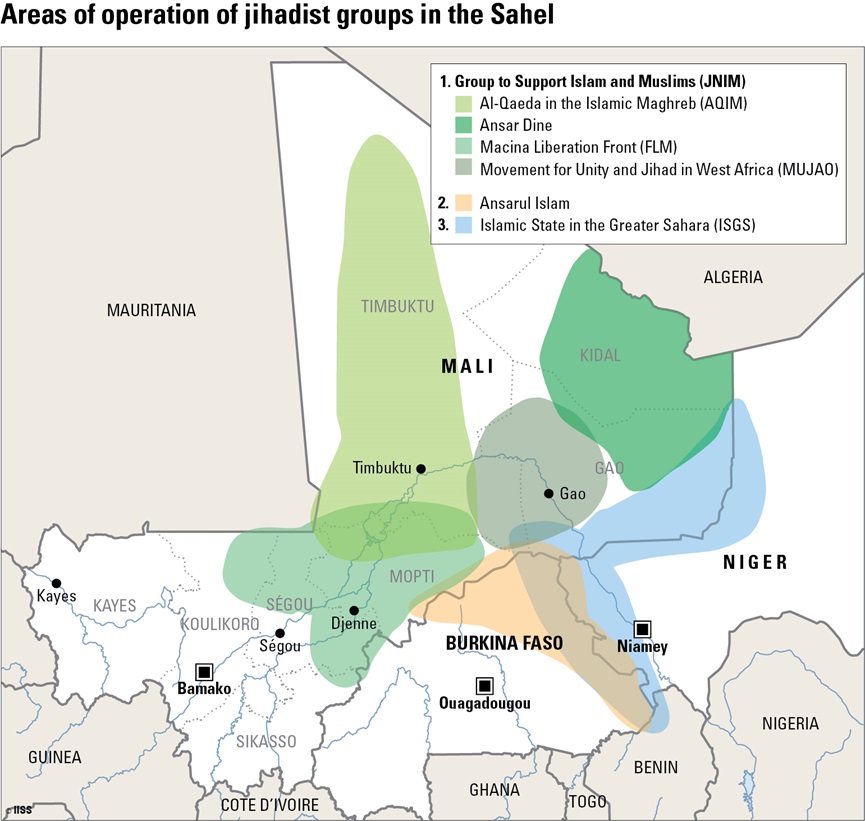

Since the French dislodged jihadist insurgents in early 2013, the groups have dispersed and reorganised. In early 2015, while the peace process between the Tuareg rebels and the Malian government was underway, jihadist groups spread from northern Mali to the central region of Mopti. The Macina Liberation Front (FLM) emerged as the lead group in this second jihadist upheaval and is responsible for the majority of attacks in the region today. As they moved south, jihadist groups took advantage of the largely unprotected border areas to conduct operations in western Niger and northern Burkina Faso.

In Burkina Faso, the violence evolved from being a spillover conflict to a fully fledged insurgency in 2018. For the first time since independence in 1960, the Burkinabe authorities have lost control over part of their country’s territory. Both the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and the al-Qaeda coalition Group for Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), in cooperation with the local Burkinabe group Ansarul Islam, have expanded their reach to the northern and eastern regions of Burkina Faso. A few attacks have even been recorded in the southwestern regions bordering Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. These developments prompted Burkina Faso’s Foreign Minister, Alpha Barry, to state in February that ‘it’s no longer just the Sahel, it’s coastal West Africa and the risk of spreading regionally.’

Ethnic fault lines exploited

In Mali, the presence of jihadist groups and the availability of weapons have fuelled an unprecedented number of inter-communal conflicts. Mali’s population is divided into several ethnic groups: Bambara (around 35%), Fulani (15%) and Dogon (9%), among others. Bambara and Dogon are mainly sedentary farmers, while Fulani are traditionally nomadic pastoralists. Tensions between communities and competition over access to land are not new in Mali, but the violence is now so brutal that many analysts are describing it as ethnic cleansing.

Feeling that their government has failed to protect them, Bambara and Dogon communities have begun to organise self-defence militias against jihadist attacks. These communities accuse the Fulani of allying with jihadist groups, an accusation they use to target Fulani communities indiscriminately.

The blame is not entirely misplaced. Jihadist groups have exploited communal tensions and the absence of the state to enhance their legitimacy and recruit mainly in the Fulani communities. They have been marginalised by the authorities, whose policies have favoured farmers to the detriment of pastoralists. Demographic pressure, agricultural expansion and desertification are slowly eating up all the land available for pasture. The authorities, driven by economic interests, have not addressed the concerns of pastoralists.

The security forces have themselves played a very active role in fuelling communal violence. They have used ethnic-based militias from various communities to conduct counter-terrorism operations in regions where they previously had little presence, sparking local resentment and distrust. They have also directly perpetrated violence against the Fulani community, pushing them further into the open arms of jihadist groups, which they see as capable of offering them a better life.

Worrying start to 2019

The first quarter of 2019 has seen a rise in jihadist activity, with the deadliest attacks against security forces in over two years and unprecedented levels of communal violence. On 17 March, JNIM attacked a Malian army base in Mopti killing 26 soldiers. In retaliation, Dan Na Ambasssagou – one of the main Dogon self-defence militia – killed 160 Fulani in central Mali a week later. In June, suspected Fulani attacked Dogon villages, killing over 70 in two attacks. This vicious spiral of violence has also spread to the Sahel region of Burkina Faso. In early April, after insurgents targeted a religious leader, inter-communal clashes between Kouroumba, Fulani and Mossi erupted, killing 62 people.

So far, the Malian and Burkinabe authorities have been unable to contain the insurgents or tackle the sharp increase in communal violence. International stakeholders – the MINUSMA, the French and the G5 Sahel – have had little success either. Failure to address the roots of the insurgency will harden communal divisions and risks further regional destabilisation.