The night before the Easter Sunday suicide bombers killed over 250 people at churches and hotels in Sri Lanka’s capital and two other towns, 28-year-old Fathima Ilham called her mother and asked her to come over the next morning. She gave no hint of the carnage that was in store, like reported by nikkei.com.

The next afternoon, the mother faced the grim truth: Fathima and her husband, 32-year-old businessman Ilham Ahmed Ibrahim, had been involved in Sri Lanka’s worst act of terrorism in a decade.

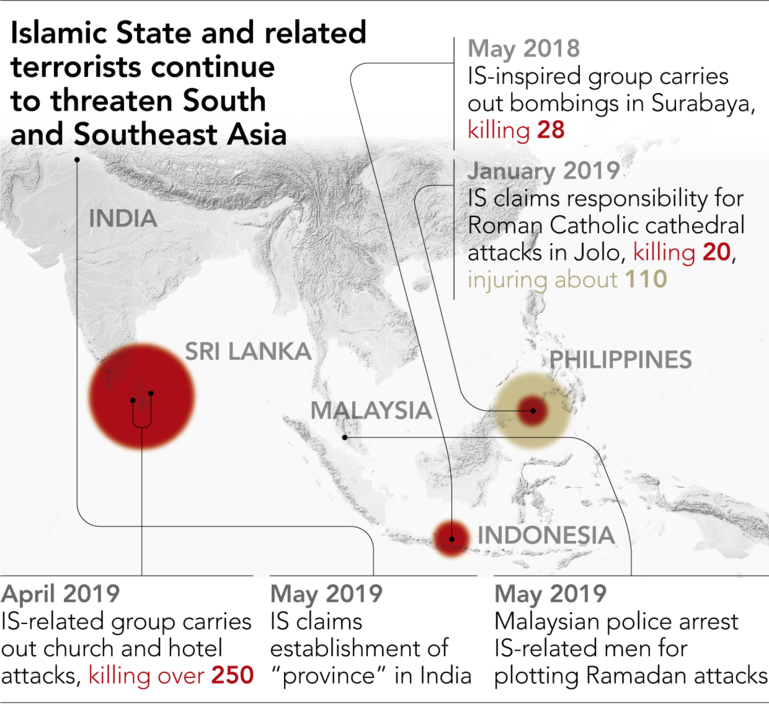

The couple’s radicalization was by no means an isolated case. The rise of families as terror cells shows how the Islamic State group and its offshoots are advancing and mutating in South and Southeast Asia, warn regional analysts who are monitoring IS-inspired extremists’ drive to establish a “virtual caliphate” to offset losses in the Middle East.

At its peak, IS controlled significant swaths of war-torn Iraq and Syria. But over the last five years it has lost almost all the territory where it had planned to build its caliphate. The group staked a claim in Mindanao in the southern Philippines — Southeast Asia’s largest Catholic country — for the caliphate in 2017, raising fears over a largely Muslim area already gripped by a nearly four-decade civil war that has cost more than 120,000 lives.

The IS call to establish a pure “Islamic environment” continues to attract Asian followers, sweeping up whole families in the process — rich and poor alike.

“This family phenomenon has a lot to do with the ideology of the IS caliphate,” said a South Asian intelligence operative. “It was an appeal to radicalized Muslims to live as true Muslims and enjoy a perfect Islamic life, which is a shift from [al-Qaida] since it never talked of creating a caliphate.”

Ilham Ahmed Ibrahim joined the cause despite his family’s status as wealthy spice traders. He was one of the two bombers who attacked the luxury Shangri La Hotel, while his brother, Inshaf Ahmed Ibrahim, hit another hotel.

Fathima, who was pregnant, blew herself up with her three infant sons hours later, after a team of police investigators arrived at the mansion where she lived with her in-laws.

Family members recalled that when Fathima’s mother visited, she had found her daughter sitting on a sofa, reciting a prayer with her sons by her side. Fathima gave instructions about payments that had to be made, then said, “I am going in the path of Allah,” before asking her mother to leave.

IS wasted no time in claiming responsibility for the Sri Lanka attacks, staged by two homegrown Islamist groups: National Thowheed Jamath (NTJ) and Jamathei Millathu Ibrahim (JMI). And the Ibrahims were not the only family involved.

Relatives of alleged mastermind Mohamed Cassim Mohamed Zaharan, the other Shangri La bomber, detonated themselves on April 26 when their hideout on the east coast was surrounded by government troops. The dead included two women and six children.

The bombings — which shattered the fragile peace in predominantly Buddhist Sri Lanka since a civil war ended in May 2009 — followed a spate of terrorism involving extremist families across the region.

In mid-March, the wife of a jihadi cell leader triggered a bomb in North Sumatra, Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country. The explosion destroyed an entire neighborhood.

In late January, an Indonesian husband and wife carried out a suicide attack on a church in the Philippines, killing 20 and wounding 102.

Back in May of last year, families — four children aged 9 to 18 and their parents — targeted churches in Surabaya, Indonesia’s second-largest city. At the time, Indonesia-based analysts described the attack as “unprecedented,” since parents were taking their children “to blow themselves up.”

The more active role of women marks a notable shift, according to the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict.

“From the beginning, they played important roles [in IS networks] as teachers, couriers, propagandists and financiers. But in the new decentralized ISIS world, they are playing combat roles as well,” the independent think tank noted in a report in April, using the alternative acronym for the group also known as Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

Counterterrorism operatives in Malaysia agree. The country’s Special Branch, an intelligence unit, has noticed how women are moving from “supporting roles to front-line roles,” said a Malaysian national security source. Alarm bells went off after a 51-year-old woman was arrested for plotting to pack her car with gas cylinders and crash it into voters at a polling station during the country’s general election in May 2018.

Malaysian security forces are on the lookout for other threats, possibly from jihadis returning home from the fight in the Middle East.

Kuala Lumpur believes over 100 Malaysians, women among them, left the country to bolster the IS ranks in the wake of the group’s dramatic rise in 2014. Jakarta estimates that over 500 Indonesian did likewise, while Colombo’s estimate is 32, including some entire families. But the vision of a Middle Eastern caliphate has gone up in the smoke left by U.S.-led military strikes.

India faces the same worries about returning fighters. The southern state of Kerala became fertile ground for recruitment: Over 20 affluent, well-educated men and their families left to join IS in 2016. Some were doctors and engineers, while others had business degrees.

The Muslim-majority Maldives, which has a population of 400,000, saw somewhere between 250 and 450 leave to join the movement. That made the necklace of islands, better known for idyllic resorts, the largest supplier of IS recruits per capita. The volunteers included 61 men who took their wives and children through Turkey to IS camps in Syria, according to the country’s counterterrorism body.

Mosharraf Zaidi, an adviser to Pakistan’s foreign ministry, has analyzed the IS influence in his country and believes it is instructive for understanding the group’s appeal across the social and economic spectrum.

There is the “worker bee level of terror operator,” who fits the stereotype of being poor, illiterate, young and impressionable, he said. And there is also the “ideological warrior,” who is wealthy and educated.

“The ideological warrior is capable of speaking English fluently and is very, very deeply invested in a civilizational narrative about how the world works,” Zaidi said.

Some of the Easter Sunday suicide bombers and their suspected allies fit this second profile, hailing from families of means and having received a foreign education. Security analysts say the same was true of the squad of Bangladeshi Islamist extremists who attacked an upmarket cafe in Dhaka in July 2016, killing 29, most of them foreigners who were dining.

IS claimed responsibility for that attack through its AMAQ news agency, just as it did after the suicide bombings in Sri Lanka.

Seasoned observers also link the spike in Islamist extremism in Asia to the proliferation of the Wahhabi and Salafi ideologies since the 1980s. Propagated by Saudi Arabia, these strains of Islam have been blamed for promoting intolerance that has spawned terrorist networks including al-Qaida and IS. And they have seeped into Asian communities that had practiced more moderate forms of the religion.

Explosives experts, meanwhile, see another troubling connection between mushrooming IS cells in Asia: the materials they use.

The Easter bombers used TAPT, or Triacetone Triperoxide — a substance al-Qaida dubbed the “Mother of Satan” for its destructive power. The same explosive was used in the bombings in Indonesia this past March and in May of last year.

“TAPT has become a popular explosive among terrorist groups, because you can get the basic material from hardware stores and supermarkets,” said Phill Hynes, the lead terrorism expert at ISS Risk, a Hong Kong-based security consultancy. “You don’t have to go to Syria or Iraq to learn the bomb-making skills.”

Sri Lankan investigators think the terrorists who struck with military precision on Easter honed their bomb-making techniques within the country. A brother of Mohamed Zaharan, who detonated explosives when troops surrounded the eastern hideout, is suspected of having been one of the bomb makers.

But piercing the network of the NTJ and JMI plotters is no easy task for the authorities. “They kept most of their conversations about the plans within the family, and also depended on face-to-face exchanges rather than leaving a trail on the Internet,” said a Sri Lankan intelligence operative.

“Inshaf and Ilham would have meetings with Jameel in a BMW for hours after finishing their early morning prayers,” the operative said, referring to another, British- and Australian-educated bomber.

Experts say investigators must get to the bottom of the Sri Lanka bombings fast. Before the attacks, the South Asian country had barely registered on the radar of new IS frontiers. Now it is seen as an indication of what IS-inspired networks are plotting.

Ethnic tensions in countries like Sri Lanka only add to the volatile mix. The Easter attacks triggered an anti-Muslim backlash, but analysts caution this could simply fuel further radicalization.

Hynes said extremists could try to take advantage of local grievances, “exacerbating them and turning them into rallying points or touchstones for the IS trend in Asia.”