The recent attacks in the UK (London Bridge and Borough Market on 3 June 2017 and Manchester Arena at a concert by Ariana Grande in May) as well as the attack at the Resorts World in Manila, Philippines (June 2017) raises a question on how the Islamic State thrives in finding a willingness to execute attacks, like reported by dailymaverick.co.za.

This article aims to provide some insight into three important pillars that facilitate extremist pathways into terror attacks, namely the meta-narrative in propaganda (the story sold to supporters), directing behaviour into action and then the complex network of associations behind attacks showing an Islamic State not only dependent on the proclivity of lone individuals.

The Narrative Sold

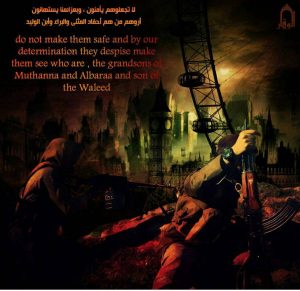

The Islamic State meta-narrative (the story as told on social media networks) is the transcendent explanation of reality proffered by Islamic State and its media apparatus. The power of this story is manifest in the emergence of the Islamic State as the most popular and influential terror group. Like any popularly adopted meta-narrative, the Islamic State involves all human faculties of perceiving reality. Visuals are arguably the dominant medium of communication in the 21st century, both for IS and its global audience; the colloquialism “a picture’s worth a thousand words” is ever truer in the Internet Age, as speed drives communication.

Some fundamental assumptions of the meta-narrativeActualising / reviving the “prophetic methodology” is the ultimate standard of good:

- Islamic State is the heir of the historical caliphates;

- Simplicity of choice where everyone else is on the wrong side of history;

- Success is confirmation of moral authority.

Much of Islamic State’s communication is clearly rooted in the past, which is not surprising in light of the above assumptions. The modus operandi of the media apparatus is to parallel allusions to a historical narrative with a narrative of life’s meaningfulness, beyond the Caliphate. It often does so by ripping off mainstream commercial products, such as video games, movies, clipart, Photoshop, and other tools for graphic design.

A Guided Narrative

The meta-narrative is not one left to its own devices, a reliance on the craze of an individual or group of people. The narrative, be it directly or indirectly, takes a lead in guiding the narrative to execution by specific references to the variety of weapons and targets.

On 26 November 2016, the Islamic State released a video, You Must Fight Them, O Muwahhid (How to attack kuffar, and how to make explosive devices). The video is one of the clearest explanations on how to create lone wolf attacks in the West with easy “how-to” tips in both English and Arabic subtitles. The first “advice” segment instructs on how to kill with a knife, encouraging knife attacks as being not just easy but also justified in the Qur’an. The detailed instructions in the video are noteworthy in the following:

- how to choose the appropriate knife (long and sturdy, such as a strong kitchen knife);

- where to strike on the the body (in order of importance: throat, heart belly, or legs) and,

- how (demonstration on a hostage).

A French speaker instructs on how to attack (approaching from behind can keep the chosen victim quiet) and how to distract your chosen target before an attack (like presenting a written paper asking for directions to a specific location such as a restaurant).

The Narrative in Action

The Islamic State’s meta-narrative in action exceeds notions of “lone wolf” attackers. The attack outside the Manchester Arena following a concert by American pop singer Ariana Grande by Salman Abedi revealed a network of family and friends traced back to Libya and Syria. Rukmini Callimachi and Eric Schmitt elaborate on the connections under investigation in an article published in the New York Times. In the article the interaction between Abedi and Katibat al-Battar al-Libi fighters in Libya are explained. Katiba al-Bittar al-Libi is an Islamic State brigade known to exist since 2013, with many of its fighters returning to Libya, making them the obvious choice in Libya for expansion.

Disconcertingly, tracing attacks back to the 2015 Paris attack to the recent attacks in the UK, the mere number of people involved in attacks and spider web of associations with the Islamic State, be it in Syria or on home soil, it is clear that what was first believed to be a relatively small group of extremists is actually an underground railroad bringing a constant flow of IS-linked militants from Europe to Syria, and back to Europe. The Terrorism, Research & Analysis Consortium’s research on attacks in Europe, since 2015, has revealed that what was first considered as a “group” of jihadists, and later as a terrorist “cell”, is in fact a much larger enterprise; neither terms are encompassing enough to define the extremists’ connections and interactions. These connections are not only traced back to Syria, but also the manner in which the individual will meet people, discover opportunities, find help in a “new community” of like-minded people, reinforcing a self-justified cause – the meta-narrative swings into action. Examples are:

- Sint-Jans-Molenbeek in Brussels, where the unemployment rate is particularly high, and where marginalisation from the Western way of life is common. Aside from the 2015 Paris, Molenbeek has also been connected to several of Belgium’s terrorism-related incidents in recent years: Ayoub el-Khazzani who opened fire with a Kalashnikov on a high-speed Thalys train had lived in Molenbeek; Mehdi Nemmouche (see below), who killed four people at Brussels’ Jewish Museum in 2014, also spent time in the neighbourhood; two suspected terrorists killed by the Belgian police in a shootout in Verviers in January 2015 were also from Molenbeek.

- Seine-Saint-Denis is one of the suburbs surrounding Paris. Similarly to Molenbeek, unemployment rates are high and marginalisation is almost omnipresent. In the aftermath of the Paris attacks, investigators found evidence that linked the Saint-Denis neighbourhood to several of the attackers: some of them had been hosted in an apartment prior to the attacks – the apartment’s landlord is currently in custody for helping them. After the attacks, the alleged co-ordinator, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, and one of his accomplices hid in another apartment in the same neighbourhood.

- Salman Abedi was born in Manchester after his parents fled Libya. Abedi reportedly was in contact with Raphael Hostey (aka Abu Qaqa al-Britani), also from Manchester, who recruited UK fighters for the Islamic State in Syria.

- Though still under investigation, the Metropolitan Police Service released a statement following the 3 June attack incidents in London Bridge and the Borough Market area, in which reference is made to 12 people arrested in Barking, east London.

The Islamic State is thus reliant on several factors to maintain the illusion of omnipresence and fighters on standby to execute attacks. In most cases, those willing to execute attacks were not instant extremists, with a history of associations with the Islamic State. Herein is the Islamic State’s weakness: the meta-narrative does not easily find a nest to roost in instant extremists.