Before Islamist militants attacked the Sinai town of Sheikh Zuweid last week, they smothered it with largess.

A local group that claims allegiance to Islamic State handed out flour to help relieve food shortages during frequent clampdowns by the military over the last two years. They distributed cash to make up for income lost in recent unrest and offered U.S. dollar salaries to lure young men to their ranks, according to residents.

The handouts, coupled with long-standing grievances of government neglect in the area, have helped Islamic State embed in the strategic peninsula between Israel and mainland Egypt—one of the most sensitive parts of Middle East.

As a result, the sparsely populated and largely lawless desert that was once a buffer between former foes Egypt and Israel has now become a liability for both countries.

The pivotal position of Sheikh Zuweid came into sharp focus last week when the Islamic State affiliate that calls itself the Province of Sinai killed at least 21 Egyptian soldiers in an attack, according to the military.

The military, which has severely restricted access to the area, says more than 200 militants were killed over three days of fighting in a bid to take the town last week.

Israeli analysts said last week’s onslaught near the border and rocket launches from Sinai into southern Israel aim to stir friction between Israel and Egypt by inviting retaliation. Any Israeli military incursion into the neighboring territory, however, risks exposing Egypt’s military weakness and straining their strategic alliance.

“We have an urgent interest in seeing the Egyptians win the war,” said Eli Shaked, a former Israeli ambassador to Egypt. “They must win the war; It’s in the interest of Israel.”

Egypt’s government insists that it maintains total control of the restive region.

On Saturday, President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi visited the military command center in North Sinai, where he accused the foreign media of distorting the size of the attack.

He said the military would have put down the insurgency quicker if it didn’t make “every effort to preserve innocent life” during combat.

Yet the rise of an Islamic State offshoot in Sinai and the government’s crackdown have caught the local population in a bind. Most are indigenous Bedouins who have been given the stark choice between supporting a violent insurgency or a government that they have long complained provides them with little support or protection.

Islamist militants have exploited the army’s mistakes, said Ismail Alexandrani, a researcher who specializes in North Sinai.

“Since the state is absent in the sense of governing, and Egyptian society is paying no heed to their plight, the little offered by [Islamic State] tempts deprived citizens.”

Mr. Alexandrani said the militants, who espouse a socially conservative brand of Islam traditionally observed by the Bedouins, took advantage of the marginalization of the local population.

The government relegated them to working in agriculture in the arid region while favoring Egyptians from the mainland for jobs in civil service, the military and trade in the peninsula.

Responding to attacks on security personnel, Mr. Sisi further angered local residents last year when he ordered the razing of thousands of homes to create a buffer zone along Sinai’s eastern border with the Gaza Strip.

The Palestinian territory is at the northern tip of Israel’s frontier with Sinai.

“The state didn’t even bother to provide relief or safe shelters to those displaced,” said Mohamed el-Manai, a resident of Rafah, the town that straddles the Gaza-Sinai border and has borne the brunt of the home demolitions.

Mr. Sisi has repeatedly urged state agencies to mitigate the suffering of the affected residents and his government has earmarked one billion Egyptian pounds ($127 million) to this end.

Still, a government-funded study released in March found that many had not received the government aid, and had resorted to living in shacks with no running water or electricity.

The Sinai Peninsula, which Egypt only fully regained control of from Israel in 1982 after the two countries signed their historic 1979 peace treaty, has long been treated by Egyptian authorities as an important buffer zone with its neighbor.

But even as tensions eased between the two nations, the region continued to suffer economically.

The lawlessness of the region has offered militants leeway to win support of local residents and punish those who resist them.

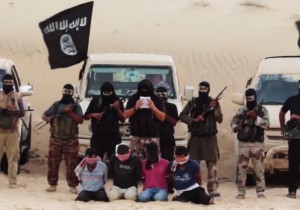

The Province of Sinai was formerly known as Ansar Beit Al Maqdis before pledging allegiance to Islamic State and the precursor group broadcast at least two videos in 2014 showing the execution of men they accused of cooperating with the military and Israeli intelligence services. Witnesses said the executions have continued, though they have not been made public through Islamic State’s vast media network.

In an effort to establish some control over the region, since 2013 the Egyptian government has been targeting the sophisticated smuggling networks that have underpinned the local economy for decades while feeding the supply of weaponry into Egypt from the Gaza Strip and Libya, on Egypt’s western border.

But residents accuse security forces of killing innocent civilians in these counterterrorism operations. The Egyptian military has never officially acknowledged civilian deaths, but only says it makes efforts to minimize them. On the streets of Sheikh Zuweid, however, the military is now being compared unfavorably to Islamic State.

“Targeting women and children in their homes has become the norm,” said a woman from the town. “When I pass the armed group’s checkpoints, I don’t even get harassed.”