Recent arrests show the Islamic State’s growing presence in East Africa, where they are recruiting young Kenyans for jihad abroad and raising fears some of them will return to threaten the country.

Kenyan intelligence agencies estimate that around 100 men and women may have gone to join the IS in Libya and Syria, triggering concern that some may come back to stage attacks on Kenyan and foreign targets in a country already victim to regular, deadly terrorism.

“There is now a real threat that Kenya faces from IS and the danger will continue to increase,” said Rashid Abdi, senior analyst at the International Crisis Group think tank in Nairobi.

The problem of eager but often untrained extremists gaining terrorist skills with IS and coming home to launch attacks is one European nations are already grappling with, and may soon be Kenya’s problem too.

“It’s a time bomb,” said George Musamali, a Kenyan security consultant and former paramilitary police officer.

“People going to Libya or Syria isn’t a problem for Kenya, it’s what they do when they come back.”

The first Al-Qaeda attack in Kenya was the 1998 US embassy bombing and the most recent large one a university massacre in Garissa last year, but the IS threat is new and as yet ill defined.

In March four men appeared in court accused of seeking to travel to Libya to join IS.

Then in early May, Kenyan police announced the arrest of a medical student, his wife and her friend accused of recruiting for IS and plotting an anthrax attack. Two other medical students were said to be on the run.

Police chief Joseph Boinnet described a countrywide “terror network” linked to IS and led by Mohamed Abdi Ali, a medical intern at a regional hospital, “planning large scale attacks” including one to “unleash a biological attack… using anthrax”.

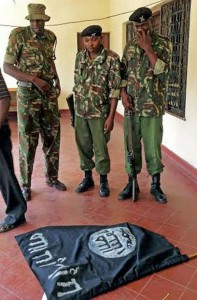

Three weeks later Kenyan police announced (using another IS acronym) the arrest of two more members of “the ISIS network that is seeking to establish itself in Kenya in order to conduct terror attacks against innocent Kenyans.”

Police said they had found “materials terrorists typically use in the making of IEDs” — homemade bombs — as well as “bows and poisoned arrows”.

Some experts dismissed the suggestion of an imminent large-scale attack in Kenya, but said the threat of IS radicalisation, recruitment and return is genuine.

“We can’t see either the intent to carry out such an attack nor any real planning for it,” said one foreign law enforcement official who has examined the anthrax allegation.

“But there is something in it: there is IS here, mainly involved in recruitment and facilitation.”

Martine Zeuthen, a Kenya-based expert on violent extremism at Britain’s Royal United Services Institute, said the recent arrests “indicate that radicalisation continues to be a serious security concern”.

She said that while recruitment into the Somalia-based Al-Qaeda group Shabaab remains the primary danger, “there are also credible reports of recruitment from Kenya to violent groups outside the region, such as those fighting in Libya.”

“Like those who went to fight in Somalia and returned to Kenya, this new category of recruit may also return and pose a security risk to Kenya,” said Zeuthen.

Kenyan authorities already struggle to manage the return of their nationals from Somalia, where hundreds of Kenyans make up the bulk of Shabaab’s foreign fighters.

In the future they will likely also have to deal with returning IS extremists as well as self-radicalised “lone wolf” attackers inspired by the group’s ideology and online propaganda.

“Kenya risks finding itself fairly soon in the position that Belgium or France or the US does, as IS-inspired extremists pose a domestic threat,” said Matt Bryden, director of Sahan Research, a Nairobi-based think tank.

“In Kenya, we’re not yet at the point where experienced fighters are coming back but it may not be far off.”

Bryden and others believe that for now the true number of Kenyan IS recruits may be just “a handful” but the existence of sympathisers with the capacity to help aspiring jihadis travel to Libya and Syria, often via Khartoum, Sudan, is not in doubt.

IS is a new entrant to a well-established jihadist scene in Kenya, exploiting the diverse grievances of angry, frustrated and disaffected young Kenyans.

Recent security operations on Kenya’s coast have forced Shabaab recruiters into retreat, inadvertently opening up space for IS.

“Success in dismantling the organised jihadi networks has created a vacuum into which IS is stepping,” said Abdi. “There is a proliferation of jihadi groups, and that makes for a much more dangerous situation.”

digitaljournal.com