“Wanted” was emblazoned across photographs posted online by Islamic State.

Files bearing Islamic State logo showed faces of Egyptian military and police officers, alongside names, addresses, and ranks, urging followers to hunt them down and kill them.

All the men listed were not domiciled in Sinai, the thinly populated and rugged peninsula bordering Israel and Gaza where the Sunni militant group has been waging an insurgency for more than three years; they were from elsewhere in Egypt.

The files were posted on Telegram, an encrypted instant messaging system used by IS to communicate with its followers, like reported by reuters.com .

Coupled with the group’s highest profile attack outside Sinai, the bombing of Cairo’s Coptic Christian cathedral in December which killed 28, the online campaign shows that the group has extended operations to the rest of Egypt, a key U.S. ally seen as a bulwark against Islamist militancy in the region.

In turning its sights on targets outside Sinai, Islamic State puts more pressure on the government of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, presents new challenges for security services and threatens a potentially heavy blow to tourism, a cornerstone of the country’s already battered economy.

Islamic State claimed responsibility for seven attacks in Cairo last year, after mounting four in 2015.

“Islamic State has had Egypt as a target – and not just Sinai – as part of its discourse for quite a while now, and independent security analysts, as well as official statements from the Egyptian state, show that attacks beyond Sinai have increased in the last couple of years,” said HA Hellyer, senior non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington.

Egypt’s interior ministry did not respond to requests from Reuters for comment on wider IS operations and how the government was reacting.

BROADENING THE INSURGENCY

Hundreds of Egyptian soldiers and police have been killed fighting the Islamist insurgency in Sinai. It has gained pace since mid-2013 when General Sisi, then military chief, ousted President Mohamed Mursi of the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s oldest Islamist movement, after mass protests against his rule.

Militant group Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (Supporters of Jerusalem), bolstered by recruits from disenfranchised Bedouin tribes, had been fighting government troops in Sinai since before Mursi’s ouster. It pledged allegiance to Islamic State and changed its name to Sinai Province in 2014, the year Sisi was elected president.

When the group claimed the cathedral bombing, its statement did not bear Sinai Province’s logo. It said “Islamic State Egypt”.

“When the attacks are claimed by ‘Islamic State in Egypt’ and not simply ‘Sinai Province’, it is a clear expression from them that they are not simply going to target Sinai, but the broader country,” said Hellyer.

Sisi denied lax security was to blame for the cathedral attack. “Do not say it was a security flaw; what happened was an act of desperation,” he said.

Sisi cracked down on the Brotherhood and other Islamists after Mursi’s removal and the dragnet widened to include opposition activists and journalists. Human rights groups estimate at least 40,000 political prisoners were detained.

Sisi does not make a distinction between the Brotherhood, which says it is peaceful, and Islamic State. The Brotherhood denies resorting to violent tactics despite the government often linking it to attacks, including the cathedral bombing.

Islamic State propaganda regularly portrays the Brotherhood negatively and its statements have called Mursi an apostate.

CHANGING TACTICS

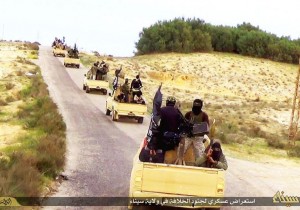

Islamic State strategy in Sinai mirrors its tactics in Syria and Iraq, security analysts say. It fights with a clear command structure using roadside bombs, suicide bombers and snipers.

Its mainland Egypt operation, however, is more like its cells in Tunisia or Europe. It relies on small, secretive groups that do not communicate with each other using techniques it publishes online, such as how to make home-made bombs.

The cells, or lone operators, then carry out attacks in Islamic State’s name and the main group claims responsibility.

“These cells live normally amongst the population until it is time to strike. Security agencies foiled some, but Islamic State is now using that strategy in Cairo on a larger scale,” said Khaled Okasha, security analyst and former police officer.

“Islamic State is not going to stop at Sinai and is betting on its mainland operations in the coming period.”

As Islamic State loses ground in Syria, Iraq and Libya, it is reasonable to assume their focus will shift towards Egypt, the Arab world’s most populous nation, security analysts say.

Attacks in Cairo in the last two years included attacks on a tourist bus, a police truck, a security checkpoint, the Italian consulate, a homeland security building and a police chief.

The military judiciary is currently trying 292 suspected Islamic State militants, some of whom are accused of plotting to assassinate Sisi. Only 151 are in custody.

The military has killed at least 2,000 members of Sinai Province since the group pledged allegiance to Islamic State in November 2014, according to its statements.

‘TRACKING DOWN THE APOSTATES’

“Support the jihadis and report the information of apostates around you be they soldiers, agents, conscripts, policemen, officers, bank managers, Christian leaders, atheists, crusaders or Zionists who live among you,” Islamic State urged its supporters online.

It provides a system by which supporters can send over the required information. The “Tracking Down the Apostates of Egypt” campaign is advertised as an alternative for supporters who cannot join the fight in Sinai.

Still, maintaining a strong presence in Sinai appears to be an Islamic State priority, said Stephanie Karra, North Africa analyst at Risk Advisory in London.

“The capabilities of IS cells in and around Cairo are in no way comparable to those of IS in the Sinai,” she said, adding: “But it’s worth keeping in mind that a strategy IS has used in other countries is to mount attacks outside their areas of control to reduce military pressure on the group.”

Islamic State has made no demands of the Egyptian government, which it aims to topple. It says it fights to install Islamic sharia law and establish a global caliphate to which it wants to add Egypt. The government says the group has tried to assassinate Sisi more than once.

PRESSURE ON SISI

Sisi has called Islamist militants an existential threat and has made security a priority for Egypt, a country of more than 90 million people that has a peace treaty with Israel and which receives substantial military aid from Washington.

He campaigned in 2014 on a platform largely based on fighting terrorism and often tells Egyptians they were saved from the conflicts besetting Syria, Iraq, and Libya when he ousted Mursi.

More attacks would further damage the ailing tourism sector, and a main source of foreign currency in this import-dependent and dollar-strapped country.

Egyptian beach resorts, its pyramids and other cultural treasures took a hit after the political instability of the 2011 uprising that ended Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule.

It was then dealt a big blow in October 2015 when a Russian passenger plane was blown up over Sinai, killing all 224 people on board. Islamic State claimed responsibility.

British flights to the Red Sea resort of Sharm al-Sheikh from where the plane took off were suspended, as were direct flights from Russia to the whole of Egypt. Officials say they are close to restoring flights, but intensification of Islamic State’s campaign in Cairo and elsewhere would create further obstacles to any recovery in tourism.