The first sign that one is entering Boko Haram’s self-declared “caliphate” in north-east Nigeria is that there are no signs. All around the town of Michika, which fell to the sect in September, gunmen have daubed black paint over signs written in English, be it advertising a local church or simply giving directions to the next town.

For a group whose motto is “Western education is sin”, all foreign scripts are deemed “haram” or forbidden – except for the Quranic Arabic with which it writes its own fundamentalist logo. One such logo can be seen on a captured Nigerian army tank, a black circle bearing the inscription “There is no God but Allah” painted just beneath the business end of the tank’s gun.

Today, though, the tank serves not as a symbol of Boko Haram’s triumph, but its defeat. The rusting, Soviet-era T72 now lies abandoned by the road, just one of many wrecked and burnt-out vehicles left by Boko Haram now that the Nigerian army is finally pushing them out.

Sat amid dusty copses of baobab and birch trees, Michika was part of a large chunk of Nigeria’s Adamawa state that was seized by Boko Haram last autumn. In the language of the local Kamre tribe, the town’s name means “creeping in silently”. Boko Haram’s arrival, one Sunday last September, was anything but.

“The day beforehand, a group of soldiers came running past our homes, saying: ‘Get out of here, Boko Haram are coming’,” resident Matthias Andrew, 42, who fled first on foot and then by cattle truck, told The Telegraph.

“The next day, just half an hour after Sunday church service, they arrived in a convoy with their headlights on in full daylight, and when people ran away they shot at them.”

“They slaughtered people like goats,” added Immanuel Gabriel, 34, whose wife and five children were kidnapped by the group. “My wife and kids were released by them four months later, but they killed my father, and step-brother and his two children.”

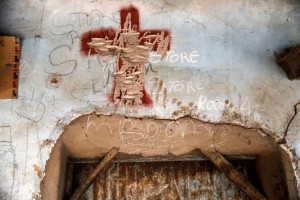

Now, with Boko Haram cleared from Michika and several other towns near Nigeria’s mountainous border with Cameroon, some of the 400,000 locals who fled south to the city of Yola are coming back, returning to burned-out houses, ransacked banks, and desecrated Christian churches and cemeteries.

Most though, are not going home because they think it is safe, but to plant the crops ahead of the forthcoming rains that provide their only livelihoods.

The threat from further attacks remains high, and when The Telegraph visited Michika with an army escort on Sunday, a local imam who acted as a guide, Dauda Bello, prayed for safe passage before departing. Even with a pick-up truck full of soldiers armed with AK47s and a belt-fed machine gun, it was not considered safe to linger anywhere for long.

On the potholed road north from Yola, the destruction grew greater with every passing town. Barely a single town hall, school or hospital remains intact. Market places and bullet-ridden shop fronts still stand largely deserted, even though four months have now passed since Michika was liberated. Most of the road’s bridges have been blown up by Boko Haram to halt the army’s advance, forcing traffic to forge across rivers that will become impassable during the rainy season.

“People have no choice but to come back, but there is a real risk that they will be cut off,” said Mr Bello, as a group of farmers pushed an ageing lorry stuck in the riverbed.

The prospect of being isolated from outside help explains the nervous looks on the faces of local soldiers, who man a thinly-spread series of sandbagged checkpoints outside each town. Some have tanks parked out of sight down side streets, but others have help only from the Civilian Joint Task Force, the polite name for the local vigilantes, who are armed with sticks, machetes and homemade firearms made by a local gunsmith.

“We are here to protect our towns,” said Samuel Markus, 30, whose gun comprised of an ancient flintlock firing piece bound with masking tape to a wooden stock. The stock had the words “AK47” hand-carved on the side, even though the weapon fired only shotgun pellets.

Nonetheless, army officers say the vigilantes have been useful in helping them track down Boko Haram fighters within the local population, who either sympathised with the group in the first place or joined up opportunistically when they seized control.

The challenge now though is stopping that vigilante force turning into a sectarian revenge squad. For although Boko Haram terrorised both Muslims and Christians in the likes of Michika, local Christians believe they suffered the brunt of it. While a handful of local mosques have been destroyed, there is barely a single church left standing. Many local worship sessions are now held under mango trees.

Mr Bello favours preaching forgiveness, and says that ultimately, efforts will have to made to reintegrate those who joined Boko Haram back into their communities. “They may still have some of the Boko Haram ideas, so they will need careful examination,” he said.

Even he concedes that suspicions are likely to linger, and in the meantime, scores are being settled in a more robust way. While The Telegraph was in Michika, word went round that the vigilantes had caught a “Boko Haram suspect” and were giving him a stiff beating just a block or two away.

Asked if we could investigate further, the officer leading our army escort shook his head and said it was time to move on.