Four weeks after his body had been blown apart by a Hellfire missile, Al-Qaeda third-in-command Mustafa Abu al-Yazid delivered his last testament, like reported by firstpost.com. “I bring you good tidings,” his voice declared, through a tape posted online in the summer of 2010. “Last February’s India operation was against a Jewish locale in the west of the Indian capital, in the area of the German bakeries—a fact that the enemy tried to hide—and close to 20 Jews were killed”.

Few Indian counter-terrorism analysts believed the speech made sense: indeed, it was wrong on every significant detail, bar the fact that Pune’s Germany Bakery had indeed been bombed. That operation, though, was known to have been conducted by the Indian Mujahideen’s Mohammed Ahmed Siddibappa, also known as Yasin Bhatkal—with no known connections to Al-Qaeda.

Now, it’s clear India should have listened harder. The speech in fact described the first meetings between Indian jihadists and Al-Qaeda, leading up to last week’s declaration of war against India by Al-Qaeda’s chief. Even now, though, many experts dismiss the Al-Qaeda threat, arguing the real threat comes from Inter-Services Intelligence backed jihadist groups, not a mainly-Arab organisation without local roots.

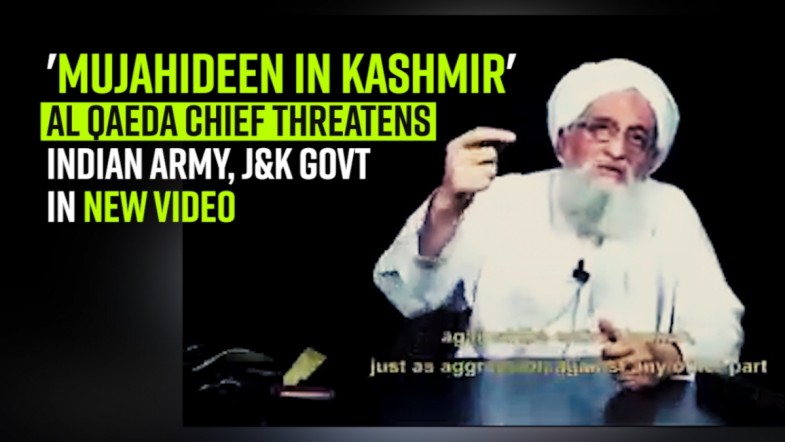

This comforting wisdom is simply wrong: Al-Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahiri’s war against India isn’t a new adventure, but a homecoming. Even worse, from India’s point of view, the dice are rolling the jihadist group’s way.

In 1980, when al-Zawahiri arrived in Peshawar to help lay the foundations for the Afghan jihad, he was no stranger to the milieu he found himself amidst. His maternal grandfather, Abdul-Wahab Azzam, a professor of oriental literature and president of Cairo University, had served as Egypt’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Yemen—and, in 1954, Pakistan. He had, notably, translated the poet-laureate of South Asian Islamists Mohammad Iqbal into Arabic.

For decades before the world started paying attention, Islamists in the Arab-speaking world and South Asia had engaged each other, laying the intellectual foundations for the long war they hoped would come. Karachi was the crucible for the process—and al-Zawahiri’s grandfather a key catalyst.

In his years as envoy to Pakistan, Azzam’s closest friends included Said Ramadan—son-in-law of the Islamist ideologue Hassan al-Banna, and the de-facto foreign minister of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. Pakistan’s prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, had met Ramadan in 1948, when he visited Karachi to attend a World Muslim Congress. The relationship flowered through the early 1950s, with Khan even giving the Muslim Brotherhood leader a weekly radio programme to air his views.

Ramadan, journalist Caroline Fourest has recorded, “was omnipresent in the media, arguing, on every occasion, for legislation based on the Shari’a”. Ironically, this enterprise had support from the Central Intelligence Agency, which saw the Muslim Brotherhood as a hedge against communism.

The most important relationship to develop during this time was that between the leader of the Jama’at-e-Islami, Abul’ Ala Maududi, and the Egyptian Islamist ideologue Sayyid Qutb—then, a rising star in the Muslim Brotherhood. Introduced through Ramadan, the two men laid the foundations for the ideology that would flower into Al-Qaeda.

Persuaded that Hindu revivalism posed an existential threat to Islam in South Asia, Maududi advocated for a Shari’a-based, militarist state. Islam, he insisted, was not just a religion; it “is a revolutionary ideology which seeks to alter the social order of the entire world and rebuild it in conformity with its own tenets and ideals.”

Thus, Maududi concluded, it was imperative for Muslims to “seize the authority of state, for an evil system takes root and flourishes under the patronage of an evil government and a pious cultural order can never be established until the authority of government is wrested from the wicked.” To do this, Muslims must “eliminate un-lslamic governments and establish the power of Islamic government in their place”.

In his book Milestones—which fired the minds of generations of jihadists, including al-Zawahiri—Qutb seized on Maududi’s ideas. He acknowledged the intellectual debt, reproducing extended tracts in the Jama’at leaders’ 1939 essay, Jihad in the Way of Allah.

“Let me tell you what is it that makes the destiny of a nation,” Iqbal’s poem Bal-e-Jibril says, “the sword and dagger must take precedence over singing and dancing”: for everyone from Maududi to Ramadan, and Qutb to al-Zawahiri, this much was apparent.

“Liberating the Muslim nation,” wrote al-Zawahiri in Knights Under the Banner of the Prophet, released by al-Qaeda on the eve of 9/11, “confronting the enemies of Islam and launching a jihad against them, require a Muslim authority, established on a Muslim land, that raises the banner of jihad and rallies the Muslims around it”. He warned jihadists: “Without achieving this goal, our actions will mean nothing more than mere, repeated disturbances.”

Almost two decades later, it’s clear events didn’t pan out as al-Zawahiri hoped. Even though Al-Qaeda-affiliated movements today control far more territory than in 2001, there are no signs of the kind of revolution that would enable the creation of a state to act as a vanguard for the jihad.

From 2011, when al-Zawahiri took charge of Al-Qaeda, his mind has turned ever-more to South Asia. Building a subcontinental front to wage jihad, he believes, began to become an operational objective—its intimate alliance with the Taliban offering the keys to unlock the strategic objective of state power.

Early in 1996, when Osama bin Laden returned to set up base in the Taliban’s Afghanistan, references to India began appearing in Al-Qaeda literature. That year, for example, he issued a declaration condemning “massacres in Tajikistan, Burma, Kashmir, Assam, the Philippines, Pattani, Ogaden, Somalia, Eritrea, Chechnya, and Bosnia-Herzegovina”.

Al-Zawahiri’s 2001 book, similarly, called on Muslims to discharge “a religious duty of which the nation had long been deprived, by fighting in Afghanistan, Kashmir, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Chechnya”.

After 9/11, the anti-India references in Al-Qaeda literature became more marked, appealing to the regional Islamist milieu by charging the Pakistani state of collaboration with Hindus and Jews. In September, 2003, for example, al-Zawahiri invoked India to warn Pakistanis that their President, General Pervez Musharraf, was plotting to “hand you over to the Hindus and flee to enjoy his secret accounts.”

Then, in 2007, Pakistani military ruler General Pervez Musharraf ordered troops to storm the neo-fundamentalist Lal Masjid seminary in Islamabad—catalysing a fateful shift in the politics of jihadist groups.

Abdul Rashid Ghazi, the seminary’s chief, was a graduate of one of Pakistan’s most famous Islamist centres, the Jamia Uloom-e-Islamia, which counts among its alumni Masood Azhar, the leader of the Jaish-e-Muhammad, Qari Saifullah Akhtar, who headed the Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami, and Fazl-ur-Rehman Khalil, the leader of Harkat-ul-Mujahideen.

Led by al-Zawahiri, a new phalanx of jihadists hostile to the Pakistan Army emerged in Miranshah. There, Al-Qaeda allied with Muhammad Illyas Kashmiri, the leader of Brigade 313 and a former Kashmir jihadist.

From multiple accounts, it’s clear at least some numbers of former members of the Indian Mujahideen—India’s most successful urban terrorist group—moved to join this grouping in Miranshah. Interestingly, jailed 26/11 perpetrator David Headley had told the FBI of a “Karachi project” run by Kashmiri, with plans to target India.

This group included Sana-ul-Haq, the Uttar Pradesh-born, Deoband-educated jihadist who now runs Al-Qaeda’s south Asia operations. Haq became involved in jihadist circles following the demolition of the Babri Masjid in December 1992, the year after he graduated from Deoband. He left India, and joined the Jamia Uloom-e-Islamia in Karachi.

Haq was mentored by Nizamuddin Shamzai, a powerful cleric closely linked to the Taliban and al-Qaeda, who had bragged of being treated as a “state guest” in Mullah Muhammad Omar’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

Later, he briefly taught at at the Dar-ul-Uloom Haqqania seminary in Peshawar, before becoming an instructor at the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen’s training camps in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

In 2013, Haq delivered an exhortation specifically targeting Muslims in India—the first of its kind in global jihadist writing. He invoked anti-Muslim communal violence in India, saying “the Red Fort in front of the mosque cries tears of blood at your slavery and mass killing at the hands of the Hindus”.

Even though Al-Qaeda is yet to stage operations of any significance against India, it has steadily developed the infrastructure it needs for a sustained campaign. In Kashmir, Al-Qaeda’s fledgling unit has attracted a small but steady flow of jihadists.

For India, new dangers lie ahead. First up, the apparently-inexorable return of the Taliban to state power in Afghanistan will give its Al-Qaeda allies the shelter of state power—a necessary condition, as al-Zawahiri understood, for the success of the jihad. Having learned from 9/11, Al-Qaeda will refrain from targeting the West, for fear of losing its state.

To demonstrate its jihadist credentials—and compete for legitimacy with rivals like the Lashkar—Al-Qaeda will instead focus on strategically less-dangerous targets, like India. For its part, the Pakistani state is likely to welcome such a project. Forced to temper its anti-India operations by international pressure, the ISI will see in Al-Qaeda a means to pursue its tactical ends by proxy.

Put simply, the jihadist threat is likely to become infinitely more complex, and dangerous, in the years to come. New Delhi would be wise to begin preparing itself to fight al-Zawahiri’s new war.