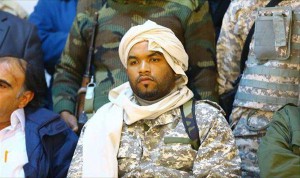

Ibrahim Jadhran has gone from an alleged car thief imprisoned in Colonel Muammar Qadhafi’s most notorious prison to a warlord in charge of a powerful militia sitting on billions of dollars of oil money.

Now he’s one of the most important players in an effort to end the chaos that has torn Libya apart since Qadhafi’s overthrow in 2011: He has thrown his weight behind the U.N.-backed Government of National Accord (GNA), signing a breakthrough deal to reopen Libya’s oil ports.

Jadhran is the chief of the Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG), a militia force of more than 20,000 men that is supposed to protect the country’s vital oil industry. Speaking in the large boardroom of his office complex in the deep-water port of Ra’s Lanuf, in the oil crescent of central Libya, he spelt out his supposed conversion.

“I am a Muslim but I consider myself a moderate,” said Jadhran, who had shed his normal military uniform for a dark suit. “And it is because of that I chose the middle … The area where we sit now is in the middle of Libya. It is my country’s security valve and it is the beating heart of Libya’s wealth.”

His voice matters both because of the men and the money he controls. Jadhran has been an extremely skillful player in the turmoil of post-Qadhafi Libya as militias, tribes and rival governments — an internationally recognized one in the eastern city of Tobruk, and a more Islamist one called the General National Congress (GNC) based in the capital Tripoli in the west — battled for control.

In mid-2013, Jadhran closed two major oil export terminals, demanding the GNC government give eastern Libya more autonomy, particularly over oil revenues, and branded the former management of the National Oil Company corrupt.

His brand of maverick separatism increased and, in March 2014, he allowed an oil tanker named the Morning Glory to set sail from the eastern port of Sidra under the North Korean flag. It was promptly stopped and boarded by the U.S. Navy.

Jadhran claims the Morning Glory crude oil shipment had been authorized by the Tobruk government, but the Tripoli government tried to stop the tanker, and the incident led to the ousting of Prime Minister Ali Zeidan.

Now Jadhran denounces all sides. He accused the GNC of being dominated by Islamic extremists. Jadhran in turn was accused of not doing enough to stop ISIL when the terror group seized part of the central Libyan coast that had been under the control of his forces.

Jadhran is also critical of the eastern legislature in Tobruk, which he claimed was seeking a military dictatorship under General Khalifa Haftar, who led an assault on the GNC government and remains a powerful warlord.

“We stood by the government, but at the time the National Congress started to lean toward the Islamists and then the parliament [House of Representatives in Tobruk] leaned towards the militarization of the state and the return of a dictatorship. So we saw that we were the only ones standing in the middle,” said Jadhran.

Jadhran supported a national political dialogue and it was this process that led to the December formation of the new U.N.-backed government in Tripoli. “We released a statement of support three hours after the GNA was formed despite the fact it was almost political suicide to support its newly-born presidential council,” he said.

Call to arms

Others point out that Jadhran’s loyalty to the GNA came at a price, the payment of his 20,000 plus PFG forces of all their back salaries.

Mattia Toaldo, policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, is critical of what he called Jadhran’s “opportunistic choices” but is pragmatic about his importance to Libya’s political future.

“Jadhran remains in the eyes of many Libyans a very controversial figure,” he said. “Yet, the truth is that along with Defence Minister Mahdi Al-Barghathi, he’s the only easterner who supported the GNA from day one and the GNA needs not just the oil he sits on but his loyalty.”

That support for a new and internationally recognized government, complete with a signing ceremony — attended by tribal leaders — to reopen the ports is something of a change for Jadhran. He’s been embroiled in his country’s violent politics since the war that ousted Qadhafi.

The son of an army officer, the muscular 34-year-old had spent the previous six years in the notorious Abu Slim prison, where he was sent at 22 for a life sentence for what he says was his political activism, but which records suggest was for car theft. However, Qadhafi never called anyone a political prisoner and inmates were branded pretty thieves, traitors or spies.

“I was released three days after the spark of the February 17th revolution,” said Jadhran. “Because the demonstrators calling for change were met with live fire and mortars from the Qadhafi regime, peaceful protest was not possible and we were forced to take up arms. Young men found themselves forced to carry arms and return fire on an enemy.”

He formed a battalion of volunteers to defend Libya’s oil crescent around Ra’s Lanuf and Ajdabiya, his hometown. “I managed to gather 16 battalions under the one flag, all of which participated in the revolution.”

In a deeply divided country, Jadhran defended Cyrenaica, the east of the country that has traditionally been hostile to the Tripoli-dominated west and slowly took over Libya’s oil infrastructure.

Now he controls the four main oil ports of Ra’s Lanuf, Zueitina, Sidra and Brega, many oil wells and hundreds of miles of pipelines and says that his goal is to protect the oil wealth that accounts for 97 percent of Libya’s economic output

His forces helped oust ISIL fighters from key oil terminals and in recent weeks have led assaults on key ISIL locations along Libya’s coast. He has also followed through on his promise to allow for renewed oil exports under a unified National Oil Company.

“The issue of selling and marketing oil is strictly the business of the National Oil Company, it has been entrusted to carry out this mission by the government and the people of Libya,” he said.

This week, the House of Representatives voted against the GNA in a no confidence motion. The vote means that Jadhran’s commitment to the GNA, together with his influence in the east and control over the security of oil exports, are even more vital to Libya’s future.

So the question is, what does Jadhran want? The answer seems to be political respectability and to present the PFG as an example of good governance to encourage investment back into Libya.

“There is no doubt that I have high expectations in assuming a high and honorable position and that this position should be for the good of the people,” said Jadhran. “If Libya becomes independent, its institutions secured within a real democratic and good governance blueprint, then this will enable international investment companies to re-enter Libya.”

politico.eu