In the summer of 1990, at a fulcrum moment when his country was tipping from reform to dissolution, Mikhail S. Gorbachev spoke to Time magazine and declared, “I detest lies.” It was a revolutionary statement only because it came from the mouth of a Soviet leader, like reported by nytimes.com.

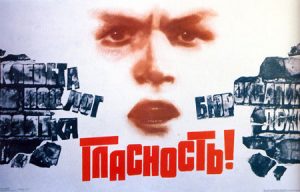

On the surface, he was simply embracing his own policy of glasnost, the new openness introduced alongside perestroika, the restructuring of the Soviet Union’s command economy that was meant to rescue the country from geopolitical free-fall. Mr. Gorbachev was wagering that truthful and unfettered expression — a press able to criticize and investigate, history books without redacted names, and honest, accountable government — just might save the creaking edifice of Communist rule.

For the Soviet leader, glasnost was “a blowtorch that could strip the layers of old and peeling paint from Soviet society,” wrote the Baltimore Sun’s Moscow correspondent (and now Times reporter) Scott Shane in “Dismantling Utopia: How Information Ended the Soviet Union.” “But the Communist system proved dry tinder.”

We in the West have always praised Mr. Gorbachev for his courage in taking this gamble — even though he lost an empire in the process — but he did it under pressure. The idea that a better relationship with facts might be liberating for a corrupt and ailing Soviet Union was not new. Mr. Gorbachev was echoing and appropriating the arguments of a dissident movement that, for decades, had made an insistence on truth its essential form of resistance.

If the Soviet Union was the 20th century’s greatest example of a regime that used propaganda and information to control and contain its citizens — 70 years of fake news! — the centenary of the Bolshevik Revolution is an important moment to appreciate how it also produced a powerful countercurrent in the civil society undergrounds of Moscow and Leningrad.

True internal pushback against the Soviet regime began to emerge only in the 1960s, at the moment when the political temperature inside Russia was moving from post-Stalinist thaw back to chilly. The suppressions began with the trial of the satirical writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky in early 1966. As protests and further trials followed, the dissidents were faced with an interesting dilemma: how to fight back most effectively in light of the information that was coming their way. Almost daily, they would hear the details of interrogations, stories passed around about life in the labor camps, and the drumbeat of searches and arrests.

The dissidents could have presented their own form of propaganda, hyping the persecution and turning that rich Soviet lexicon of “hooligans” and “antisocial elements” into bitter screeds against the state itself. But they didn’t. They chose instead to communicate it all as dispassionately and clinically as possible. They reached for what we might call objectivity.

Generations of Soviet citizens had trained themselves to think of factuality as a highly relative concept. The newspapers were read as a narrative meant to glorify the state and not as a reflection of reality. And people likewise felt split into authentic private selves that often had nothing to do with their public faces and utterances.

Given how much of Soviet society was built on this decadeslong duplicity, it is remarkable and reassuring that speaking truly and plainly still held such power for the dissidents by the 1960s. But it did. To hear Lyudmila Alexeyeva, one of the early organizers of a key underground journal engaged in this fact-gathering, A Chronicle of Current Events, describe it, the attraction was almost religious:

“For each of us who worked for the Chronicle, it meant to pledge oneself to be faithful to the truth, it meant to cleanse oneself of the filth of double-think, which has pervaded every phase of Soviet life,” she wrote. “The effect of the Chronicle is irreversible. Each one of us went through this alone, but each of us knows others who went through this moral rebirth.”

In its meticulous commitment to holding the Soviet Union accountable to its own laws and international treaties, A Chronicle of Current Events represented also a rebirth of civil society. It was a small community, and one that existed entirely on the onion-skin-thin pages of samizdat, the illegal, self-published writing of the dissidents, but this was where they could act as citizens, witnessing and reporting on violations of human and civil rights.

The Chronicle worked in a straightforward way. Issues were produced in Moscow and then passed from hand-to-hand. If someone had some piece of information to circulate, she could write it down on a slip of paper and pass it on to the person from whom she received her copy of the journal, who in turn would then keep it going along the chain. At the source were editors like Natalya Gorbanevskaya, the journal’s first “compiler,” as they preferred to call themselves. Eventually arrested by the state security agency, the K.G.B., in 1969, she was locked up in a psychiatric institution until 1972.

Over some 65 issues, from 1968 to 1983, the Chronicle became a catalog of abuses, noted in the most sparse, neutral tone possible. It was a painstaking effort to publish information that could never be obtained through the official Soviet media. Here, a citizen could read the details of closed political trials and the stories of what the Chronicle called “extrajudicial persecution,” understand what a K.G.B. search entailed, read secret documents meant only for those in power, learn about the constant religious and cultural persecution and get updates on political prisoners in the East.

This was self-consciously an attempt to create a valid and verifiable news source. The Chronicle demanded that its contributors be “careful and accurate” with any information they passed along and even ran regular corrections to previous items (pioneering a practice some Western media organizations only adopted years later). As the scholar of Soviet dissidence Peter Reddaway, writing in 1972, put it, “the Chronicle’s aim is openness, non-secretiveness, freedom of information and expression. All these notions are subsumed in the one Russian word, glasnost.”

This was in direct opposition to the diktat the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin had issued for newspapers, back in pre-revolutionary Russia in 1901. The press was to be “not only a collective propagandist and collective agitator, but also a collective organizer” — a tool, in other words, for shoring up the power of the state. For the compiler Alexeyeva, the Chronicle represented something very different and without precedent in the Soviet Union: “A source of honest information about the hidden layers of our society.”

The K.G.B. did not take kindly to this business, and Gorbanevskaya was only the first of many editors to be arrested and imprisoned. By the 1970s, though, this fact-based evidence-gathering had become the central modus operandi of the dissidents, especially among its most prominent figures like Andrei Sakharov, the Soviet physicist who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. These were men and women who, in some cases, were professionally inclined toward facts — many of them were scientists, a vocation they adopted, even before they embraced dissidence, out of a conscious effort to move away from any field that could be distorted by Communist ideology.

In 1975, the Soviet Union, thinking it was outsmarting the West, signed on to the Helsinki Final Act. The pact offered international recognition of its territorial gains following World War II, but it also demanded adherence to international human rights norms. Moscow dissidents saw this as an opportunity: They could use this commitment against the apparatchiks, by claiming the right to publish every violation.

The Moscow Helsinki Watch Group, as the monitoring organization became known, followed the style of the Chronicle, producing a range of reports, all scrupulously researched and running sometimes to hundreds of pages. Among the first were investigations of the persecution of Crimean Tatars and the poor caloric intake of prisoners. The reports were delivered to Western embassies, as well as circulated in samizdat form. Soon, copycat watchdog groups popped up in other Eastern bloc countries, and even in the United States. The one based in New York, Helsinki Watch, became the organization we know today as Human Rights Watch.

Did this underground quest for truth based on scrupulous, objective reporting hasten the downfall of the Soviet Union?

That is hard to say, since so many other factors, economic ones especially, also contributed to the collapse of Russian communism in the late 1980s. But it did impact the way the Soviet Union ended. Unlike China, which also faced a major challenge to its authority in 1989, the Soviet Union could not hope to reform itself through perestroika alone. As Mr. Gorbachev’s adoption of the word “glasnost” conceded, there had to be change in civil society as well.

The dissidents had created an expectation that a different kind of language was possible, one that expressed a reality not filtered through Soviet imperatives. They craved honesty and transparency in a country where even the suicide rate was considered a state secret. Samizdat provided the outlet.

And facts, relentlessly stacked one on top of another, became the dissidents’ way of building the different Russia they hoped might one day emerge and overcome all the lying.