A three-series multimedia project by the New York Times reveals how current Kremlin disinformation campaigns stem from a long tradition of weaponizing information. Titled “Operation Infektion”, the series tells the story of a “political virus”, invented decades ago by the KGB to “slowly and methodically destroy its enemies from the inside”, and which the Kremlin continues to deliberately spread to this day.

EU vs Disinfo takes a closer look at each of the episodes and encourages you to watch them yourselves.

“A lie is halfway around the world before the truth has even got its boots on” said Mark Twain. Or perhaps it was Winston Churchill? As the New York Times points out, this quote has been attributed to many different authors. However, its main point is firmly supported by scientific research: lies spread faster than facts.

In the final episode of its “Operation Infektion” series, the New York Times documents the world-wide war on truth and asks the question which is rising higher and higher up the political agenda: how do we defend ourselves against disinformation?

While there is no simple cure for the disinformation virus, exposing it is a start.

Since its inception in 2015, the East Stratcom Task Force has identified and collected over 4,500 cases of pro-Kremlin disinformation. And we are not alone in this.

There is Estonian Propamon – a monitoring robot which looks for news related to Estonia in Russian media, and an AI driven myth-debunking initiative in Lithuania. But robots are not enough. That’s why there are also a lot of humans who dedicate their time and efforts to exposing disinformation.

Created by a university professor and his students, StopFake became a go-to resource to learn about Russian disinformation tactics in Ukraine. MythDetector tracks and debunks anti-Western disinformation. Digital Sherlocks identify, expose, and explain disinformation at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research lab. Polygraph verifies quotes, stories, and reports of government officials, state media and other high-profile individuals in English, while Factographdoes it in Russian. Using open sources, Bellingcat investigates online information and disinformation. TjekDet does fact-checking in Danish, Faktiskt in Swedish and Les Décodeurs – in French.

If disinformation is a virus, then public awareness is a vaccine. Examples of such a vaccine include, among others, Sweden, that took measures to increase social resilience in the run-up of the 2018 elections, Finland – home to the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats and Poland, where NGOs created a platform to raise awareness and educate society about information security.

However, as we are increasingly connected by social media, the risk of disinformation contagionis growing. To curb it, the European Union introduced the Code of Practise on Disinformation – the first of its kind in the world. The Code, signed by such online giants as Facebook, Twitter, Mozilla and Google, sets self-regulatory standards in order to fight disinformation and address the spread of fake news online.

In the meantime France is debating a new law that would oblige platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to disclose the funding sources for sponsored content in the three months that precede elections. And Germany is already enforcing a law which demands that social media sites quickly remove hate speech, fake news and illegal material.

Is that enough?

Disinformation appears to be becoming a global pandemic, or, as the New York Times puts it – we are witnessing the worldwide war on truth. So while states, media and civil societies are still finding ways to strengthen collective defence, our individual efforts matter more than ever.

Use these online resources to verify content you read on internet.

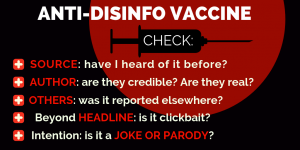

And here are some simple tips to make sure your news feed is not infected with disinformation:

- Check the source: Is this the source I think it is? Have I heard of it before?

- Check the author: Are they who they say they are? Are they a real person?

- Check with others: has this been reported somewhere else?

- Check beyond the headline: could this be a clickbait?

- Check intention: could this be a joke, satire or parody?