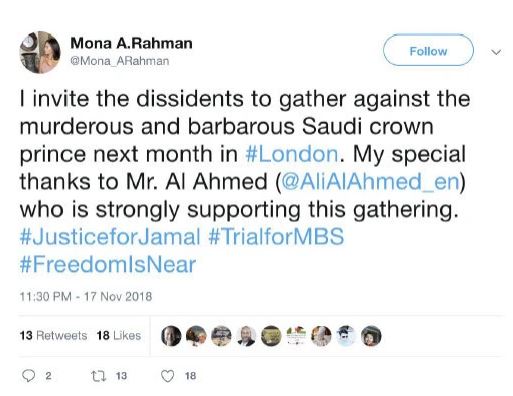

Ali Al-Ahmed is a veteran critic of the Saudi government, so late last year he was not surprised to receive a Twitter message purporting to be from an Egyptian woman living in London who said that she, too, was a Saudi opponent.

But Mr. Al-Ahmed, who is based in Washington, was wary of the woman, who identified herself as Mona A. Rahman. “Her picture was too made up, like the picture of a model,” he recalled. Her Arabic was imperfect. And her messages in Arabic included a character that indicated that she was typing on a Farsi-language keyboard.

Then she sent him an article that appeared to be from the website of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard about an unexpected development in Israeli politics.

The article was on a site that had the exact logo, coloring and layout of the Harvard site. But the address was “belfercenter.net” — not the real one, “belfercenter.org.” And the article, claiming the Israeli defense minister had been fired for being a Russian agent, was a total fabrication.

Mr. Al-Ahmed had encountered what a new report from Citizen Lab, a research group at the University of Toronto, says is a pro-Iranian influence operation that used elaborate look-alike websites and social media to spread bogus articles online and to attack Iran’s adversaries. The operation had another innovative maneuver: When the invented reports were picked up by mainstream news organizations, the operators quickly took down the fabrications to make it harder to track the fraud.

“They deleted their fake stories once they achieved some buzz,” said Gabrielle Lim, a fellow at Citizen Lab and a lead author of the report. “This made it hard for regular users to figure out what was happening, and hid the original source of the disinformation.”

Ms. Lim called the pro-Iran operation “a sprawling disinformation assembly line” that has operated since at least 2016.

“They published false stories on cloned news websites, then amplified them with well-worn, negative tropes about Israel, Saudi Arabia and the U.S.,” she said. They also created false personas like “Mona A. Rahman,” who targeted Mr. Al-Ahmed, and tried to trick legitimate news outlets into publishing their articles and even to give them bylines, Ms. Lim said.

In recognition of the group’s prolific production and its transient nature, Citizen Lab labeled it “Endless Mayfly,” after the gangly, short-lived insects that hatch and swarm every summer. Citizen Lab said it cannot say for certain that the operation was sponsored by the Iranian government. But it noted that Facebook and Twitter removed hundreds of accounts last August linked to the same operation, and Facebook said those accounts had ties to Iranian state media.

Etienne Maynier, another author of the Citizen Lab report, said Endless Mayfly’s articles “frequently echoed official comments and positions of the Iranian government.”

Raz Zimmt, an expert on Iran at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies, a think tank affiliated with Tel Aviv University, and a former Israeli military intelligence officer, said Iran has turned to cyberattacks and online influence campaigns in part because of military weakness. In addition, he said, such hard-to-trace operations allow Iran “to maintain the ambiguity needed to reduce the risk of open confrontation with opponents who maintain a military superiority over it.”

In setting up its ephemeral websites, the Endless Mayfly group used one tactic familiar from phishing operations: “typosquatting,” in which a website is created under a name a letter or two off from a well-known institution. Endless Mayfly used “theguaradian.com” to mimic “theguardian.com” and “theatlatnic.com” in place of “theatlantic.com.”

Researchers at Citizen Lab got their first clue in April 2017, after users on Reddit noticed an article on Brexit that appeared to be from the British newspaper The Independent actually came from a site spelled differently: “http://www.indepnedent.co/.” But when readers later tried to return to the article, they were sent to the actual newspaper’s official site. The article’s authors had deleted the fake one but changed the link to reinforce the impression that it had originated on the real newspaper’s site.

In all, Citizen Lab said it had identified 73 web domains created by the group, 135 ersatz articles it had posted and 11 fake identities like Mona A. Rahman, often used as bylines on the fake articles. Some of the articles had been previously flagged as false by reporters and researchers, who sometimes pointed at Russia as the likely culprit. But the overall operation has not previously been described and linked to Iranian interests.

The group appears to still be active, according to Citizen Lab, though most of its operation has been shut down. “On the surface, they look like a not-very-successful viral advertising campaign,” said John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at Citizen Lab.

Editors’ Picks

‘Although I Tried to Look Away, I Saw Him Gesture Toward Me’

How Volunteer Sleuths Identified a Hiker and Her Killer After 36 Years

Peggy Lipton, ‘Mod Squad’ and ‘Twin Peaks’ Actress, Dies at 72

But the fabricated article on Israeli politics impressed a former senior Israeli intelligence official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. The fake article concocted by the group quoted Tamir Pardo, a former director of Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, as saying in a talk at Harvard that Avigdor Lieberman, Israel’s defense minister, had been dismissed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after it was discovered that he was a Russian mole.

The fabricated article was spread on Nov. 14, 2018, through a Twitter account for “Bina Melamed,” a common Israeli name.

In fact, Mr. Lieberman had just resigned in protest of a cease-fire ending fighting in Gaza, and Mr. Pardo had just spoken at the Belfer Center. The rest of the article was an invention. But the former Israel official said he was struck by the overnight creation of the fake Harvard website and the “superfast reaction to events.”

“It shows an admirable understanding of the online world,” the official said. Months later, a search on the web for the bogus headline still turns up a few hits.

For Mr. Al-Ahmed, the Saudi critic in Washington, the Citizen Lab research simply underscored the hazards for activists online. In what appears to have been a separate operation last year, he was contacted by a woman posing as a BBC journalist who asked to interview him; she, too, turned out to be a fraud.

Based on past experience, Mr. Al-Ahmed thought at first that Mona A. Rahman might be a Saudi operator meant to entrap him. But when he learned it appeared to be Iranian trickery, he was not particularly surprised.

“I’ve been a target of all kinds of things,” he said. “All kinds of people come after me. Only the methods change.”