The Arab Spring of 2011 seems like a distant memory. At the time there were great hopes, particularly among young people across Arab capitals such as Cairo, Damascus and Tripoli. “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” wrote Wordsworth of the French revolution, “but to be young was very heaven!”

Six years later the hopes of youth have been dashed. President Assad has all but won the Syrian civil war, with 500,000 Syrians losing their lives. Out of a country of 25 million, 11 million have been displaced, and nearly five million have left the country. Yet the fate of Libya is probably even more responsible for the migration crisis in Europe than the Syrian civil war.

We can debate the rights and wrongs of our intervention in Libya in 2011. But what is clear today is that a country which had a stable government under Colonel Gaddafi is now a breeding ground for militias controlled by various warlords.

Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA) reminds one of Voltaire’s definition of the Holy Roman Empire, which he memorably said was “neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire”. The GNA in Libya cannot be described as a “national” government, neither does the existence of more than 1,500 militias suggest much accord.

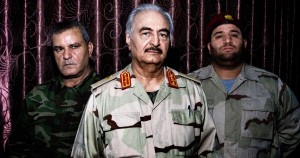

In the midst of all this chaos one figure is often referred to as a potential saviour. Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar is a 73-year-old former associate of Gaddafi. He enjoys support from Russia, Egypt and the UAE. He has control over the oil fields and much of the eastern part of Libya. The West remains committed to support the GNA.

Haftar, as one senior diplomat told me, is “a divisive figure”. But it would be difficult to think of a senior military figure in all human history who has not been “divisive”. Haftar may, however, be a source of stability in that beleaguered country.

Libya’s chaos is a human tragedy. Every week thousands of people land in Italy from the continent of Africa. Many of them will have come through Libya at some point. The country has more than 4,000 km of borders, which is the same as the distance from London to Moscow. These are currently wide open. Stories have surfaced of militias detaining would-be migrants and starving them to make them thinner so that more can fit onto ships. Each migrant is reported to pay up to $1,000 to undertake the perilous journey across the sea. There is every incentive for Libya’s militiamen to engage in this human traffic.

The situation in Libya has direct consequences for Europe and the wider world, yet very little progress has been made. It is embarrassing to say that Syria is more likely to reach some kind of political stability in the short term than Libya.

Some people are hopeful that President Trump will seize the initiative and come up with a plan to back Field Marshal Haftar. Such a move would not strictly conform to the ideals of “democratic state building” but it might provide a stable government to give Libya some control of its borders. The alternative seems to be endless discussions, debates and procrastination. None of this has yielded much fruit in the five-and-a-half years since the unlamented death of Muammar Gaddafi.

standard.co.uk