The notion that young women are travelling to Syria solely to become “jihadi brides” is simplistic and hinders efforts to prevent other girls from being radicalized, new research suggests.

Young women are joining the so-called Islamic State group for many reasons, including anger over the perceived persecution of Muslims and the wish to belong to a sisterhood with similar beliefs, according to a report released Thursday by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue and the International Centre for the Study of Radicalization at King’s College London.

Western societies must understand these varied motivations if they hope to prevent more women from joining the militants and potentially returning to their home nations to commit acts of terrorism, argue the report’s authors, Erin Saltman and Melanie Smith. Thinking of them as all being brainwashed, groomed, innocent girls hinders understanding of the threat they pose.

“They’re not being taken seriously,” Smith said. “It’s inherently dangerous to label people with the same brush.”

The researchers suggest that while the term jihadi bride may be catchy from a media point of view, the young women who are travelling to Syria see themselves as something more: pilgrims embarking on a mission to develop the region into an Islamic utopia. Many would like to fight alongside male recruits, but the group’s strict interpretation of Islam relegates them to domestic roles.

The primary responsibility for a woman in Islamic State-controlled territory may be to be a good wife and a “mother to the next generation of jihadism,” but the study concluded that women are playing a crucial propaganda role for the organization by using social media to bring in more recruits.

“The propaganda is dangerous,” Smith said. “It draws vulnerable or ‘at risk’ individuals into extremist ideologies … simplifying world conflicts into good versus evil which allows someone the opportunity of being the ‘hero’ – an empowering narrative for a disenfranchised, disengaged individual.”

Young women are often vulnerable to this kind of rhetoric because they are questioning their identities as they grow into adults. Many of the young women observed said they felt socially and culturally isolated in secular Western society, and saw the region controlled by Islamic State as “a safe haven for those who wish to fully embrace and protect Islam,” according to the report.

About 550 young women, some as young as 13, have already traveled to Islamic State-controlled territory, according to the report.

The authors combed the social media accounts of more than 100 female profiles across platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Tumblr. To grow their sample, they used a “snowball” technique in which female Islamic state migrants were identified among networks of other Islamic State networks. Photos, online chats and other accounts helped place the women geographically in Syria or Iraq. Researchers say the women came from 15 countries and were largely operating in English.

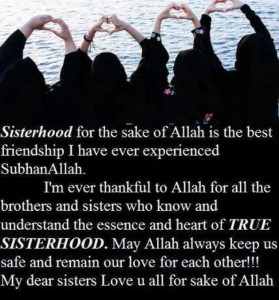

They consistently talked about the camaraderie they experienced after moving to Islamic State territory, and often used social media to post images of veiled “sisters” posing together.

“This is often contrasted with discussions about the false feeling or surface-level relationships they iterate they previously held in the West,” the authors said. “This search for meaning, sisterhood, and identity is a primary driving factor for many women to travel.”

They are also searching for romance in the form of marriage.

“Online, images of a lion and lioness are shared frequently to symbolize this union,” the report said. “This is symbolic of finding a brave and strong husband, but also propagandizes the notion that supporting a jihadist husband and taking on the ISIS ideology is an empowering role for females.”

One woman identified only as Shams and who is a qualified doctor, found her husband through an arranged meeting. He proposed immediately. She posted an image of her wedding, which features the Islamic State flag in the background. Her bearded husband wears a tie. She wears a white burqa with only a slit for the eyes.

She captioned the picture: “Marriage in the land of Jihad: Till Martyrdom Do Us Part.”

While they are enticed by romantic stories about groups of women eating by candlelight and bathing in the Euphrates, most of the young migrants quickly find that the reality of their lives belies the rhetoric.

While life in Syria is difficult, few women voice their grievances directly. Islamic State has relied on a decentralized network of “messengers” to proliferate its world vision, and the network snaps into action to quickly reprimand anyone who speaks out. The hashtag “#nobodycaresaboutthewidow,” didn’t last long.

But the women do warn those who may follow them that they should be ready to “be tested” by intermittent electricity, water shortages, bitter winters and the travails of life in a war zone. Health care is a particular concern, with one Western woman describing her experience of having a miscarriage in an Islamic State hospital because she couldn’t communicate with the doctor.

“These anecdotes serve to disprove the idea of the well-integrated, utopian society that is so strongly emphasized by ISIS propaganda,” researchers said.