The hidden backstory to the latest diplomatic blow-up between Turkey and Europe, like reported by foreignpolicy.com

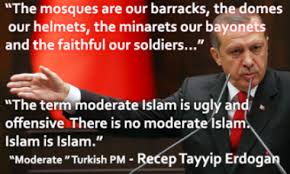

This month, relations between Turkey and the two countries home to the bulk of Turkey’s European diaspora, Germany and the Netherlands, publicly exploded in a fit of acrimony and insults. But the dispute was playing out on two levels, only one of which was immediately apparent. As impossible as it was to ignore Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s repeated accusations of “Nazi practices” by Europe, it was easy to overlook the history of mutual tension leading up to that outburst — including Erdogan’s own long-running subversion of Islamic religious institutions catering to diaspora Turks in Europe.

On the surface, the fight was over the Erdogan government’s efforts to campaign in Europe ahead of a pivotal referendum vote next month aimed at remaking Turkey as a centralized presidential state. For the first time ever, German and Dutch officials banned Turkish government ministers from making stops in their respective countries to lobby for votes, claiming that Europe’s democratic systems shouldn’t be used as vehicles to aid in Erdogan’s power grab (though it seemed more than a coincidence that the governments of both European countries were about to face re-election themselves). Erdogan responded by making his Nazi accusations and threatening to annul Turkey’s refugee deal with the EU that is said to have slowed refugee inflow into continental Europe.

That tensions reached such heights so quickly reflects the way nationalist populism can be mutually complementary across international borders. But it also reflects a longer-standing problem specific to Turkey and Europe — namely, the Turkish government’s conviction that diaspora Turks everywhere in the world owe their first allegiance to Turkey. Erdogan doesn’t just want Turkish expats’ votes; he wants their unwavering loyalty, and, to the consternation of European governments, he has proved willing to go to extreme lengths to secure it.

That includes speaking engagement by Turkish politicos and Turkish-language propaganda, and instances where the two overlap. (In an interview with a German-Turkish newspaper in 2011, Erdogan declared that “forced integration” requiring immigrants to suppress their culture and language violated international law. It wasn’t the first time Erdogan used language that Europeans felt crossed a line: A year earlier, in Cologne, Germany, he’d said, “Assimilation is a crime against humanity.”) But Erdogan’s efforts also include more subtle tactics, including shaping the religious life of Turks residing in Europe to serve his government’s political goals by using state-paid imams as spies.

The Sehitlik Camii mosque, in Berlin’s immigrant-heavy district of Neukölln, is a case in point. Until mid-July last year, it had been the site of a cautious but thoroughly progressive experiment. The mosque’s young imam, Ender Cetin, a native Neuköllner of Turkish descent, began opening up his house of worship to non-Muslim visitors: for example, holding open-house Saturdays. He began engaging in public dialogue with Jewish rabbis and Christian priests.

The Sehitlik Camii mosque, Berlin’s largest Islamic house of worship, basked in media attention for these efforts, viewed as it was by integration proponents as an exemplary initiative to cut the yawning gap between Germany’s Muslims and other Germans. But Cetin was not alone: He was part of a new generation of Muslim clerics across Germany who sought to better weave the Turkish Muslim community into the fabric of mainstream Germany. These young priests made it their business to pick up solid German or, like Cetin, hailed from Germany’s Turkish community and were born and raised here, then trained in Turkey. They reached out to the German media and ventured into German public schools to teach religion classes for Muslim pupils; a few even broached ultra-sensitive topics, such as homosexuality.

But this religious glasnost came to an abrupt halt this past summer, in the aftermath of the failed coup attempt in Turkey. The scuppered putsch prompted a crackdown across Turkey and reached into Germany, as well as other European countries with diaspora Turks.

Cetin and his allies found themselves facing the wrath of Diyanet, Turkey’s directorate for religious affairs. Diyanet is Turkey’s official Islamic authority and the paymaster of about 900 mosques in Germany — and many more across Western Europe. The directorate was created in 1924 with the aim of keeping Islam in check in secular, republican Turkey; in the era of Erdogan, critics say, it has become a political tool to further the interests of his Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP). Diyanet’s budget covers the salaries of all of Turkey’s “export imams” active in Western Europe, every one of whom is a Turkish civil servant.

In the wake of the coup attempt, the Diyanet headquarters in Ankara — one of the Turkish state’s most powerful institutions — yanked tight the leash. Cetin and others, including the entire Sehitlik Camii governing board, were unceremoniously disposed of — accused of being followers of Fethullah Gulen, the mysterious exile whom Erdogan has blamed for the coup. A note on the mosque’s entrance gate read: “Gulen supporters unwelcome.” The brief experiment at Sehitlik Camii and other Diyanet-funded parishes was snuffed out, and the faithful returned to the well-worn path of Islam they were on before; an Islam more oriented to the culture of Turkey than Western Europe — and more loyal to the party of Erdogan than any other.

The lives of many Turkish migrants, particularly older ones of first or second generation, still revolve around the insular world of the mosque parish and the Turkish community. A broad spectrum of Turkish-language newspapers and broadcast media, from the left to the far-right, are available in Germany. But most popular among those with Turkish passports, observers estimate, are probably Ankara’s official state news channels, which meticulously follow the AKP line. According to Haci-Halil Uslucan, a migration specialist at the University of Duisburg-Essen, “The Turkish media received in Germany is roughly 80 to 90 percent government-friendly, manipulative, and unilateral.” Observers say the regime’s propaganda has an even bigger impact in the diaspora: Unlike their countrymen in the homeland, the diaspora Turks don’t have the reality of everyday life in Turkey to contrast with the exaggerated reports.

The long arm of Ankara also reaches beyond its borders via the network of Diyanet imams and mosques in Europe, which is managed by the Cologne-based Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB) — the largest Muslim organization in Germany with branch offices across the country. The mosques’ function — at least until recently — has not been expressly political, nor are Turkey’s imams as a whole in the service of either Erdogan or the AKP. (There are also, in addition to Diyanet-financed mosques, independent, self-financed Turkish mosques in Germany.) But the missions of the AKP and Diyanet-funded mosques abroad dovetail ever more frequently, as the case of the Sehitlik Camii imam and a mosque-based espionage scandal in Germany last year vividly illustrate.

As the Turkish population in Germany — much of it with roots in poor, rural, and religious eastern Anatolia — swelled beginning in the 1960s, when the first Turkish gastarbeiter, or guest workers, arrived in West Germany to handle the grunt work of the booming postwar economy, makeshift mosques began to pop up in migrant districts of Germany’s inner cities, usually in the form of small prayer rooms in multistory walk-ups. There were at the time — and remain today — few sources of imams for the Anatolian workers other than Diyanet. DITIB came to life in the early 1980s in order to supply the flock with leadership and often purports to speak in the name of the Turkish community today, a fact that troubles many leftist and liberal-minded Turks in Germany.

The condition of Turks in Germany became an urgent concern in the 1980s and 1990s, when Germans belatedly took notice of the burgeoning Turkish community in their midst — and of its youngest generations filling up the classrooms of urban secondary schools. Study after study showed that Turkish children performed poorly in German schools, that Germany’s new underclass was disproportionally immigrant — and, unsurprisingly, that the Turkish community in Germany identified with Turkey and its traditions over Germany and its ways.

Observers underscored the discrimination against and exclusion of the Turkish community in Germany as the reason for the migrants’ condition. The guest workers were never meant to stay in Germany, even though 3 million eventually did so. But experts also zoomed in the use of imported imams as part of the problem — a contributing factor to Europe’s broader failures to integrate. Few of the holy men learned proper German, and their stints of four years abroad were hardly enough to understand the day-to-day lives and problems of their migrant flocks, whose lives were rooted in Germany, dealing with the German authorities, schools, employers, and neighbors. In one measure of how out of touch they were (and remain): The Friday sermons delivered weekly at the houses of worship are a one-to-one facsimile of those written by the Diyanet higher-ups in Ankara, which are delivered weekly across Turkey.

But as Erdogan has grown increasingly autocratic, Diyanet has begun to look more like a tool of the regime — and DITIB a vehicle of the conservative AKP philosophy. DITIB has become “an extended arm of the Turkish president, Erdogan,” Islam expert Susanne Schröter told Die Zeit. “Through it, the Islamic AKP ideology extends to the classrooms.”

The changed role of Diyanet and DITIB came under harsh scrutiny in Germany last year in the aftermath of the attempted coup. Not only were reform-minded imams like Ender Cetin ousted, but preachers loyal to Erdogan were also caught red-handed by German intelligence services submitting lists of suspected Gulen supporters to Turkish authorities.

The German authorities charged 16 clerics with illegal “secret service collaboration” and searched mosques and apartments, confiscating computers and reams of paperwork. One German parliamentarian with Turkish heritage called DITIB a “political proxy of Erdogan” and demanded the German government cease cooperation with it. Equally compelling evidence of activity on behalf of Ankara existed in Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands. According to Turkish media, Diyanet employed imams in 38 countries to gather intelligence on suspected Gulen followers. In Germany, DITIB issued a statement categorically denying the charges of espionage and protesting the searches.

The German weekly Der Spiegel, which broke the story, claimed that the imams’ reports at their disposal underscored how far Erdogan’s power reaches into German society. One of Erdogan’s objectives, charged Der Spiegel, was to divide the Turkish community abroad between friends and foes of the regime. It concluded: “DITIB is an important part of the web of the Turkish president in terms of Turkish citizens abroad. Erdogan considers DITIB an instrument to expand his rule in Turkey.”

On April 16, the day of the referendum, there will be voting stations in 57 countries hosting the Turkish diaspora. Germany will have voting booths in 13 cities, located in the embassy and consulates — almost twice as many as during the 2015 elections. There is no polling on how Turkish nationals abroad might vote. In addition to AKP-front lobby groups organizing for Erdogan, opposition groups are campaigning against it. “Erdogan has most probably profited from the ban on Turkish government politicians,” said said the Berlin-based Turkish journalist Ahmet Külahci, which is, according to Kulahci, exactly what he intended. Indeed, caught between the politics of two worlds, Europe’s Turkish migrants might well be the decisive factor in a pivotal vote that could confirm or reject the swing to authoritarian solutions in Europe and beyond.