Daesh, the self-declared Islamic State that planted its flag within the battered borders of Iraq and Syria, isn’t just in serious retreat, squeezed by enemies on all sides.

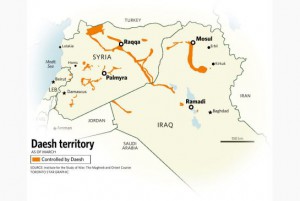

As losses mount, as leaders fall, as resources dry up, as thousands of square kilometres of ground give way — at least 40 per cent of its territory on the Iraqi side and 20 per cent in Syria in the past six months — Daesh is on a trajectory to extinction, as a geographic entity, if not an idea.

It’s easy not to see this with eyes still numb from the screaming headlines of the attacks in Brussels and Paris. But the grand jihadist project that audaciously stole Al Qaeda’s propaganda thunder, inviting like minds the world over to build a caliphate in real time — right here, right now — is withering.

The timing of the endgame remains unclear, as Daesh clings desperately to its two most important cities, Raqqa in Syria and Mosul in Iraq, still able to mobilize an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 fighters, down from a peak of more than 30,000.

It will likely outlast the rule of U.S. President Barack Obama, who leaves office in January. But a year from now, many believe, Mosul will be back in Iraqi hands. And the lights of Daesh may be gone from Raqqa even sooner.

The emerging question for security analysts isn’t so much if, or even when, Daesh will cease to exist as a territory, but what happens next. Syria, and Iraq, will remain a politically fractious mess. Where will the battle-hardened survivors go, and what are they likely to do when they get there?

“There is no such thing as a ‘virtual caliphate’ that exists only in the sky and on the Internet — the taking of land, and the holding of important cities like Raqqa and Mosul — is the entire point,” said Canadian researcher Amarnath Amarasingam, who co-directs a study of foreign fighters at the University of Waterloo.

“When you take away that core idea, when you strip away the notion of a return to a golden age of Islam, there’s a larger consequence of western kids losing their attraction.”

Canada was never a fertile recruitment zone for Daesh, which was able to attract barely 100 Canadian fighters to its cause as of 2015. That number has declined to a trickle in the past year, said Amarasingam.

“It’s now much harder to get out of Canada and much harder to get into Syria. We haven’t seen the broad Islamophobic current elsewhere take hold in Canada. And, more practically, the government since 2013 has been much better at tracking individuals who might think of leaving, including interceptions at airports,” he said.

“So we still are looking at 80 to 100 Canadians having joined Daesh. And, of those, we believe 20 to 24 have been killed.”

Will a post-Daesh landscape prove any less dangerous? One school of security thought has long worried about blowback, with highly trained survivors resetting their sights internationally after they are stripped of a local project that has consumed most of their energies. Those fears underpinned the argument for containing, rather than eliminating, the group’s hold on the Mideast map.

But as the New York Times reported this week in an exceptional investigation unpacking the events leading up to the attacks in Paris and Brussels, the two ideas were never mutually exclusive.

Daesh has long operated on twin tracks, with one set of operatives dedicated to state building and a second set dedicated to wreaking havoc, especially in Europe.

Others anticipate that surviving Daesh fighters will flee to other lawless corners of the Middle East, including Libya, where militants already fly the black flag in troubling numbers. A report earlier this month by West Point’s Combating Terrorism Centre, however, strongly disputed the risk of Libya becoming a “fallback” home for a regrouped Daesh, noting the group has attempted and failed three times to break beyond its coastal redoubt in Sirte.

Though Libya is racked with regional divisions, any attempt to transfer Daesh headquarters wholesale would leave it “a poorer and more constrained organization, deprived of personnel, revenue and the fundamental narrative tropes of governance and sectarianism that it has used to ‘remain and expand’ in Iraq and Syria,” the report concluded.

Many Daesh fighters, meanwhile, are likely to stay where they are as local militants easily able to morph out of statehood and back to the insurgency from whence they came. Some argue that process is already underway, as violence in Iraq intensifies outside areas held by the group.

One example, though it passed largely unnoticed in the wake of Brussels, was a horrible suicide attack this week at a soccer stadium in the Iraqi city of Iskanderiya, 50 kilometres south of Baghdad, killing at least 41 people, including 17 boys between the ages of 10 and 16.

Some analysts fear more such attacks as Iraq’s regrouped army, including six new coalition-trained units, mobilize for the battle for Mosul.

The upcoming operation to reclaim Iraq’s second-largest city, months in the making, comes on the heels not only of significant territorial losses, but a rising tempo of attacks on high-ranking Daesh leaders.

Last week, U.S. forces announced the death of Daesh deputy leader Abd ar-Rahman Mustafa al-Qaduli in a special forces operation near Raqqa. And Wednesday, reports emerged of the killing of Abu al-Hija, a high-ranking Tunisian Daesh commander, as he travelled toward Aleppo on orders from self-proclaimed caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

The ability to reach such high-value targets, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said, suggests the U.S.-led coalition has successfully penetrated Daesh’s inner circle.

“ISIS’s leadership is being debilitated,” Rami Abdel Rahman, director of the British-based monitoring group, told AFP. “Without infiltration of ISIS, these killings would not have been possible.”

thestar.com