Time is running out fast for Daesh, the terrorist group that first appeared in late 2013 and within months was able to claim vast swaths of Iraqi and Syrian territories on which it proclaimed its so-called caliphate, like reported by arabnews.com.

In recent days Iraqi forces were able to liberate the organization’s last stronghold in Iraq, the town of Qaim, while Daesh fighters were forced to retreat into the Syrian enclave of Boukamal. About the same time on the Syrian side, regime forces conquered the group’s last major base of Deir Ezzor, pushing fleeing militants into the Euphrates River basin, where they now find themselves wedged between government forces and fighters belonging to the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces.

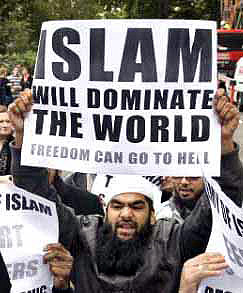

And so we reach what is being described as the “end game” in a long and costly war against one of the most brutal, and perplexing, terrorist groups in living memory. Its military defeat will constitute an important milestone for a region that has been stunned by the quick emergence of Daesh, its ability to rally supporters from all over the world and its devastating legacy that has left deep scars on the people and culture of this part of the world. Its hijack of Islam is perhaps the issue that will challenge and occupy Muslim scholars and leaders for a long time to come.

But while its downfall will be celebrated as a major victory by all those who were part of the anti-Daesh coalition, the euphoria should not overshadow a number of grim facts. Religious extremism has become a global phenomenon and while Daesh, and before it Al-Qaeda, embraced a strict, fanatical and contentious interpretation of Islam, the field remains open for other fundamentalist groups to adopt and follow similar doctrines. The task of confronting religious extremism in our region is enormous and is directly linked to social, cultural, economic and political complexities and challenges that we face.

A third wave of Islamist radicalism is therefore not far fetched, especially in countries that are going through dangerous transitions in the wake of the so-called Arab Spring and its outcome. Sectarian politics and ethno-confessional systems of government will provide fertile grounds for radical groups driven by religious zeal among people who feel marginalized and disenfranchised.

But a more immediate concern will be the fate of thousands of former Daesh fighters, including foreign militants, who had answered the call and joined the terror group, particularly in Iraq and Syria. Those who escaped will either head home or go underground, posing a clear danger to regional governments. Both scenarios present an awkward challenge. Some countries, such as Tunisia, have decided not to repatriate citizens who had joined Daesh. Others have established special programs to rehabilitate those who give themselves up. The issue is complicated and there are no easy answers.

But there is a danger that in the wake of Daesh’s defeat in Syria and Iraq, returning extremists and local sympathizers will carry out retaliatory attacks in their native lands. While the threat of attacks on major targets will slowly recede, the fear that lone wolves will be active for some time is reasonable. This year alone there have been horrific attacks against innocents in London, Paris, Barcelona and more recently in New York. All these terrorist acts were carried out by individuals who were inspired by Daesh but were not directly connected to it.

The period following the final defeat of Daesh in this part of the world will be the most dangerous. Misfits will attempt to carry out reprisals in the name of the defeated group. And while Daesh succumbs on the ground in Syria and Iraq, its proxies continue to be active in the Sinai, Libya, Somalia, Afghanistan and elsewhere. Furthermore, eliminating the group’s presence in the virtual world will prove difficult, although not impossible. It will require a global effort and some of the measures adopted by governments to regulate the online space will be controversial.

As the dust settles in the wake of Daesh’s anticipated defeat, we should begin a thorough review of the events of the past few years that enabled this fanatical cult to emerge and expand. The debate should not be limited to the geopolitical tremors and conspiracies that shook the region, but to the factors that led to the creation of the foreign extremists’ phenomenon, especially in Europe, and the support that this group with its perverted version of Islam was able to find among Sunni Muslims in Iraq and Syria and elsewhere.

As we search for answers we should not forget the thousands who perished under Daesh’s ruthless rule, the hundreds of thousands who were displaced, members of ethnic minorities who were killed, raped and enslaved and the cultural heritage that was destroyed for ever. We resolve not to let something like this happen again.