A cringeworthy video about ‘ISIS Land’ haunts past efforts to counter Daesh propaganda. A new U.S. bureau is trying learn from mistakes

In this boardroom just a short walk from the White House, which could be a boardroom anywhere in the world with creamy-white walls, a long table and an air conditioner’s hum, David Gersten is trying not to sound as boring as the room.

We’re talking about terrorism and CVE — countering violent extremism — an all-encompassing and lucrative acronym these days for analysts, academics and community organizations.

Gersten is the deputy head of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s “Office for Community Partnerships,” established a year ago. He is explaining the counter-messaging aspect of his work, the “hearts and minds” war against Daesh.

The problem is he doesn’t really want to say much. The less he says the better chance his program can succeed. “We have credibility problems,” he says. “Governments trying to counter a narrative with messages from government, isn’t very effective.”

The Obama administration has learned this the hard way.

Canada, as it moves to implement “soft” counterterrorism efforts, can learn from Washington’s mistakes.

Gersten’s department, along with a State Department initiative, is part of a new effort to combat propaganda spread by Al Qaeda and Daesh (also known as ISIS and ISIL). These programs replace earlier efforts, which Hillary Clinton during her time as secretary of state described as a cutting edge “war room” for counter-propaganda.

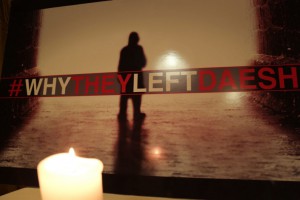

What haunts past initiatives is a 2014 video, which was supposed to counter Daesh propaganda by mocking the group and using similar shock tactics.

“Run, do not walk to ISIS Land,” the minute-long video begins. “Blowing up mosques! Crucifying and executing Muslims! Plundering public resources! Suicide bombings inside mosques! Travel is inexpensive because you won’t need a return ticket.” The text runs over gruesome images of beheadings and bombings. The end credit reads, “Think Again Turn Away,” stamped with a U.S. Department of State logo.

Although the video went viral, it was not the terrorist group that was mocked, but the government. The effort was considered about as effective as showing Reefer Madness to warn about marijuana, and showing graphic violence, as Daesh does, did not sit well with American legislators. Michael Lumpkin, the head of the State Department’s Global Outreach Center, often compares it to wrestling with a pig, “The pig likes it, and you get dirty.”

Now, both domestically and internationally, the U.S. is reaching out to credible community organizations and voices, offering funding and networking.

And yet there is still skepticism that any government partnership can work. Will McCants, author of The ISIS Apocalypse, moderated an online discussion for the Brookings Institute that was surprisingly frank. “The U.S. government has already tried everyone’s Great Frick’n Idea over and over, and no one knows when the shiny new Great Frick’n Idea was last tried and how well it did,” he writes in one post. “Staff turnover and the gigantic size of the U.S. government ensure this will always be the case. Repeated calls for co-ordination, strategy, etc. will never herd these cats.”

McCants is wary about the pledge to now partner with “credible” voices in the community, which he writes is code for “non-government people who’ll mouth my talking points but probably don’t have sway with anyone who matters.”

Yet McCants concedes that even good initiatives will not get good press, since these programs’ effectiveness is difficult to measure so criticism is the fallback — how can you keep track of those who do not join Daesh because they saw something online?

“Many people (especially journalists) are skeptical that messaging works and that U.S. messaging against jihadists can achieve anything positive, even though they can’t empirically back up their skepticism,” he writes.

Mea culpa. Having read and watched way too many Daesh propaganda posts over the last year, it does seem like a Sisyphean task to counter the group’s message. It is professionally produced, has high emotional appeal and there is a lot of it. It is even harder to imagine Ottawa, with its bureaucratic labyrinth and risk-averse reputation, spearheading anything that would be effective.

Charlie Winter, author and an associate at The Hague’s International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, who has studied Daesh’s propaganda longer than I have, shares my cynicism. But he doesn’t believe that is a reason to abandon any efforts.

“The Islamic State considers the media and information sphere as one of its key battlegrounds,” says Winter. “They have spoken about it often and I’ve come across it in official documents where they say it is as much as 50 per cent of its war.

“We have to try it. But we need to be as innovative as possible.”

“Don’t you get tired?” Umm Isa al Amrikiah, one of Daesh’s prolific writers, wrote on her Telegram channel in April. “Don’t you get tired from all this gossiping? From haram (forbidden) relationships? Are you not sick of all this haram you are doing. How can you sleep at night?”

It is not clear who Umm Isa al Amrikiah is. Or was. She was reportedly killed in May in Syria along with her husband. Her kunya, or nickname, means “mother of Isa, the American.” Her posts on the encrypted social media app Telegram disappeared around the time of her reported death.

One of her most humorous postings was “hijabi or hoejabi,” as she admonished Muslim women for speaking with men who weren’t their husbands.

Her posts are laughable to the outsider but resonated with certain impressionable women in the West. But her appeal was less about her advice, and more about her invitation to a sisterhood of Daesh followers.

She was part of the propaganda machine that is often misunderstood.

As Winter writes in a report for the London-based Quilliam Foundation, “a common misconception about Islamic State propaganda is that it starts and finishes with brutality.” But Daesh’s material is vast and nuanced, with many less publicized videos that embrace themes of victimhood, belonging, mercy and “apocalyptic utopianism.”

Then there is also a wealth of unwieldy unofficial propaganda made and disseminated by “fanboys” (or girls such as Umm Isa) to promote Daesh’s narratives.

Norwegian academic Thomas Hegghammer, who studies online propaganda, says those westerners curious about Daesh are drawn in for deeply personal reasons, which is why the mass messaging governments create to counter Daesh will not work.

“I don’t think we should worry too much about persuading them intellectually,” Hegghammer said in an interview from his Oslo office late last year. “This idea that there’s a theological code or program that you can just feed into these brains and they’ll be persuaded that their interpretation of Islam is wrong. I don’t think that’s going to be very effective.

“Nobody thinks people join military because they agree with the finer points of that country’s foreign policy doctrine, but for some reason we think people join Muslim groups because they have been persuaded by some theological text,” Hegghammer said. “People join (the military), to the extent that they join for political reasons, for vague ideas, big ideas, and a whole lot of other reasons, such as camaraderie, or the lifestyle. Same here, they join for vague ideas, defending Islam, fighting injustice, and later on they come to learn the theological mumbo jumbo.”

The boredom factor

Interviews with more than a dozen academics and analysts who study propaganda worldwide bring disappointing conclusions — there are disagreements about what works, and it seems governments are almost always playing catch-up.

Recent revelations show just how heavily the U.S. and U.K. have invested in running covert counter-messaging programs. The Guardian reported that contractors overseen by Britain’s Ministry of Defence produced videos, radio broadcasts, social media posts and even military reports stamped with logos of “moderate armed opposition” groups to try to distract from Daesh’s broadcasting.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalists along with the Sunday Times also found that the Pentagon gave a controversial British PR firm more than half a billion dollars to operate a secret program in Iraq that produced short TV segments made to look like Arabic news broadcasts.

Last month, Jigsaw, Google’s think tank devoted to tackling thorny geopolitical issues, announced a new tool called “Redirect,” which essentially uses patterns of online activity or keywords for those searching for Daesh material, to place advertisements that present countervailing content. The ads, developed by the U.K.’s Moonshot CVE, a data-based tech start-up, and Beirut-based Quantum Communications, attempt to demystify and contradict Daesh’s messaging and are as subtle as the State Department’s “ISIS Land” was loud.

It is too early to determine if this method or any of the other methods will succeed, but at best it can steer the curious elsewhere.

Yet it is rare that propaganda alone will persuade someone to fly to Syria, or plot an attack at home. A tweet may be the bait, but what follows is a personal connection. Counter the messaging is one thing — then what?

Seamus Hughes, deputy director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, says this is a worrying gap in the U.S.

“If you look at the cases, families are hiding passports, taking these ad hoc measures that aren’t working and eventually their children end up in jail or in ISIS. That is not an acceptable policy response to a problem,” he says.

Near the end of our boardroom conversation, Gersten and I somehow end up talking about the popularity of Pokemon Go and he becomes more animated.

“I have to play it because I have five teenagers,” he explains. One of his 13-year-old triplets got him out roaming the neighbourhood on a recent weekend at 9:30 p.m., and Gersten was amazed by how many people were out searching for imaginary characters on their phones.

He brings us back to the topic of counterterrorism and how the game relates. This comparison — which he admits is overly simplistic (and I promise him the headline will not be “Daesh Go”) — is essentially a vision of how to reach those vulnerable to Daesh.

“Pokemon Go actually challenges two things that some research demonstrates leads to violent extremism — boredom and isolation.”

“What is Pokemon Go doing? It’s getting people out and about, meeting people in their neighbourhoods and it is seriously relieving boredom.”

thestar.com