The war robbed him of a homeland but in the refugee camp there was no future. That’s why Abdallah and his friends returned — to fight as child soldiers against Mali’s hated government

Abdallah’s war is only a short bus ride away. Mali, Abdallah’s long-suffering country, is 40 kilometers (25 miles) from the house where the shy boy is now crouched on the floor.

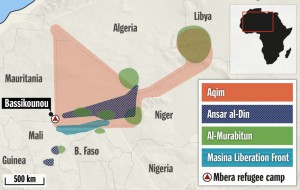

Abdallah was 11 when Tuareg rebels launched an uprising against Mali’s central government in 2012. He fled westward with his family, and they ended up in the Mbera refugee camp in Mauretania, not far from the border.

Today, Abdallah is a 15-year-old boy with black curls and a shy, questioning look in his eyes. He has just arrived for the second stay in the giant refugee city in the Mauritanian desert. Before coming back, he had returned to Mali — as a skinny boy with a Kalashnikov around his neck. Abdallah was a child soldier.

Friends had told him about the Tuareg’s fight against the government and he returned with them to Mali where, upon reaching his hometown, he joined an armed group. Abdallah had gone to fight in the same war that had prompted his family to flee.

Why does a boy do something like this? Perhaps because, with his almost complete lack of education, he felt that there was hardly a future for him in a camp like Mbera. Work as a day laborer, like his father? He would rather not. Be stuck in the camp for months, or even years, with no goals and nothing to work for? No. What does a boy want to be: A nobody? Or a warrior?

Abdallah now lives in a makeshift home. The Mbera camp is a collection of tents with a market in the middle, two infirmaries and several deep wells. It is the largest camp in the Sahel zone. Abdallah, like most of the residents, is a member of the Tuareg people, who live as nomads and herdsman, their lives adapted to the harsh conditions of the desert. They hate the Malian government, with many Tuaregs saying they are forgotten and discriminated against by the state on a daily basis.

About 41,000 people live in the camp on the southwestern edge of the Sahara Desert, where they are registered by the UN Refugee Agency and supported by the global community. The European Union and Japan are the camp’s biggest donors. Thanks to about three dozen aid organizations, the tens of thousands of refugees in the camp hardly lack for anything. The Mauritanian police provide security, doctors treat minor injuries and vaccinate the children and camp residents receive 30 liters of water a day, along with food. Even the livestock is cared for.

Recently, though, there has been a minor change. Now, instead of only providing refugees with the food equivalent of 2,100 kilocalories per person per day, the camp has become part of a new system that aid organizations across the world are experimenting with: Refugees now receive a third of their rations in the form of cash. In Mbera, that amounts to about 3 ($3.35) per camp resident each month. The goal is to help them feel like they have more control over their lives.

The sum is, of course, paltry — but it does take a small step toward acknowledging the fact that there is a serious problem when people live in a place where they have nothing to do and are at a safe distance from a war zone: They lack prospects, purpose and something to do.

A spokesman for the UNHCR says that the organization does not encourage refugees to return home. But those who do wish to go back can pick up their papers and receive a 70 travel subsidy. Their native Mali is still unsafe: Islamists are dropping bombs, rebels are fighting and the government is striking back — and the trip alone is extremely dangerous. Still, more than 1,400 people have opted to leave the camp for home thus far this year. “This is not a life for us here,” says one man who decided to take the risk. He is doing it for his family, he says, for his children.

Teenagers are a very vulnerable group in a refugee camp. They and their families have made it to safety, but there is no real future in the tent city. Mbera is in the far east of Mauretania, Hodh Ech Chargui, the poorest region in an already dirt-poor country. Almost 4,700 children attend elementary school in the Mbera camp. But what happens when they are finished?

A few hundred of the more than 10,000 adolescents in the camp qualify for slots to continue their education. And this spring, for the first time, 99 of them completed a Malian high-school education. They can hope to find a job with an aid organization in the camp.

One of the fortunate ones is 16-year-old Tinalbarka Walid Amano. Her family is from a family of musicians in Bamako, the capital of Mali, and one of her brothers lives and works in Belgium. She is also the face of a UNHCR promotional film about World Refugee Day. She is well aware of the opportunity she has been granted.

And the others?

Abdallah, the former child soldier is crouched on the floor of a mud house in the Mbera refugee camp. He gazes cautiously over his crossed arms, which are resting on his thin knees. His one-word answers are difficult to hear, because he whispers them into the crook of his arm.

“Fifteen,” is his age. “Business,” is his father’s profession. Did he attend school? “Madrassa.” A Koran school. When did he leave the regular school? “Fourth.” He means the fourth grade. He left the school because “friends” were attending the religious school. He also returned to Mali to fight with “friends.”

He can only withstand the gaze of the man who is recording his story for the UNHCR for a few moments. Abdallah is unable to say what he did in the war, or what the war did to him. Carrying an assault rifle didn’t make him more self-confident.

It is known that both Islamists in Mali as well as the pro-government Tuareg militias have trained and deployed child soldiers. Officials with the NGO that attends to child soldiers in Mbera know that at least five other adolescents from the camp fought in the war in nearby Mali. The aid workers fear that the number could even be as high as a few dozen.

Like Abdallah, two other boys also talk about their experiences fighting for the Tuareg. Eighteen-year-old Ahmed says that he rode on patrols for the MAA rebels and also fired his gun — and hit someone, he thinks. He says that he “defended a free Azawad,” using the Tuareg name for Mali’s northern provinces. In 2012, they and Islamist gangs proclaimed an independent state in the region. The government only regained the upper hand when the French military intervened. The case is clear for Ahmed: The Malian army is obviously the aggressor. The rebel group signifies protection, he says, and besides, he has nothing else to do. “I would go back and fight for my brothers,” says Ahmed.

UNICEF and the UNHCR want to prevent that from happening. The aid workers have provided Ahmed with a small shop, which he runs together with another former child soldier. Ahmed estimates that there were about 50 adolescents in his unit.

One of Mbera’s six elementary schools is on the way back to the UNHCR headquarters. Children are playing in the courtyard, running around and shouting. When they see a camera, they run toward it, throw their hands in the air and gleefully shout: “Azawad! Azawad!”

The battle cry of the Tuareg rebels in nearby Mali is part of their children’s game.

spiegel.de