With two other mysterious spy planes now retired, U.S. Special Operations Command appears to have fully transitioned to using newer, modified de Havilland Canada Dash-8s for certain discreet persistent surveillance missions. At least one of these planes is already becoming a regular feature over Libya, where American special operators continue a secretive hunt for terrorists, including individuals with links to the infamous Benghazi attack, like reported by thedrive.com.

According to the U.S. military’s latest budget request for the 2019 fiscal year, which it released in February 2018, U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) operates at least two of the twin engine Dash-8s as part of a fleet of aircraft known as SOCOM Tactical Airborne Multi-Sensor Platforms, or STAMP. That program also oversees at least three smaller twin engine Beachcraft King Air B300s.

We don’t know the exact configuration of these Dash-8s. Federal Aviation Administration records only shows SOCOM as having registered one aircraft of this type, which carries the U.S. civil registration code N8200L, so the exact status of the other plane is unclear.

But we do know that N8200L’s previous owner was Dynamic Aviation, a contractor that had operated the plane as a surveillance platform on contract to the U.S. Army. Dynamic flew a number of Dash-8s for the Army in two configurations, known by their program names Desert Owl and Saturn Arch.

Desert Owl’s primary sensor was a PedRad 7 synthetic aperture radar capable of creating images across an area nearly two miles wide depending on the aircraft’s altitude. It also had a sensor turret with electro-optical and infrared cameras.

The Saturn Arch aircraft carried a “Mission Sensor System,” as well as another sensor called “Big Green.” We don’t know exactly what these pieces of equipment did, but at least one of them could have been a laser imaging system.

Those aircraft also carried a secondary camera turret, as well as another hyperspectral camera, which could create pictures based on an object’s electromagnetic signature, and compact wide-area optical camera system.

It is possible that the Desert Owl planes had additional sensor suites, as well. All of the aircraft, which looked similar externally regardless of configuration, featured satellite data links to transmit information back to ground exploitation stations or share it with troops on the ground in near real time.

With this equipment on board, both types of planes had the mission of performing persistent surveillance missions across relatively wide areas, using their sensors to build larger maps of entire regions. From there, analysts could examine the imagery for items of interest, potentially establishing so-called “patterns of life” for specific terrorists or small groups of militants.

The Army primarily employed them to hunt for improvised explosive devices and, by extension, to trace insurgent movements back to bomb workshops or other base camps. That same wide-area surveillance information can help U.S. forces determine when the best most might be to try and kill or capture a particular individual with as little risk to nearby innocent civilians as possible.

It seems very likely that SOCOM’s Dash-8s have a similar combination of wide-area sensors given that the U.S. military routinely tasks special operations forces with tracking small groups of terrorists across vast areas where the enemy might be able to use the terrain or local populations to otherwise hide their movements. The aircraft may also have additional signals intelligence equipment to detect and monitor enemy communications, especially cell phone signals, in order to help refine their search areas.

The Pentagon’s 2019 fiscal year budget request includes $5 million for SOCOM’s STAMP aircraft, but all for upgrades to the smaller B300s, including the addition of a piece of equipment nicknamed “Tincup.” It is entirely possible the Dash-8s may also carry that system, whatever it is.

We already know that from details regarding the Army’s future Dash-8-based RO-6A spy planes that the platform is big enough to carry a robust combination of cameras, radars, and signal grabbing systems, which you can read about in more detail here. That service bought a number of the other Desert Owl and Saturn Arch aircraft from Dynamic in order to turn them into the RO-6As.

These aircraft will eventually replace all of the Army’s older EO-5C intelligence gathering aircraft, which use the de Havilland Canada DHC-7 airframe. The Canadian planemaker, now part of Bombardier, stopped making the aircraft in 1988 and built less than 120 of them to begin with, meaning they’ve been steadily more expensive to operate and difficult to support.

Bombardier continues to make versions of the Dash-8 family, meaning there is more ready source of common spare parts and support services. And though it only has two engines, each one of the Pratt & Whitney Canada PW100 turboprops on the newer aircraft is twice as powerful as that company’s older PT6s found on the DHC-7, giving them better range and endurance.

It seems that SOCOM came to a similar conclusion and when it decided to send two DHC-7s of its own to the Bone Yard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona in August and September 2017. Pictures of those aircraft also suggested they carried a diverse combination of sensors.

The FAA’s online database says SOCOM formally took ownership of N8200L in September 2017. As of February 2017, however, plane spotters and online flight trackers had begun picking up that aircraft, now wearing a more discreet civilian-style paint scheme, flying missions over eastern Libya from Souda Bay on the Greek island of Crete in the Mediterranean. The island is home to a U.S. Navy base, which serves as a common base of operations for American forces in the region.

This isn’t particularly surprising. Before then, SOCOM’s two shadowy DHC-7s – often mistaken for Army EO-5Cs – had made regular flights in the same areas of Libya.

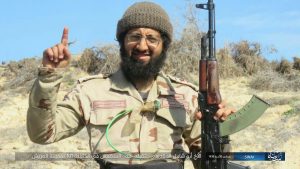

We don’t know who the planes may be looking for, but it’s very possible they are a continuing the search for individuals who participated in the attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi on the night of Sept. 11-12, 2012. Militants killed U.S. Ambassador to Libya Christopher Stevens, as well as three CIA contractors – Glen Doherty, Sean Smith, and Tyrone Woods – setting off a manhunt, dubbed at least in part Operation Jukebox Lotus, that continues to this day.

In June 2014, U.S. special operators captured Abu Khattala, who the U.S. government accuses of being instrumental in planning the attack, in Benghazi. In October 2017, another raid into Libya bagged Mustafa Al Imam, in connection with the incident. Persistent aerial surveillance would have been essential in planning both of those missions.

It is also possible that N8200L could be supporting continued American operations focused on preventing ISIS-linked militants from establishing a firm foothold in Libya. In 2016, the United States launched a brief aerial campaignto help Libyan government forces retake the eastern city of Sirte, with special operators on the ground reportedly helping coordinate those air strikes and monitor enemy movements.

Since then, the U.S. military has continued to launch sporadic targeted strikesagainst ISIS-affiliated terrorists in Libya. Between September and November 2017, U.S. Africa Command publicly announced 10 separate strikes in the country, which could have been the product of intelligence from special operations elements in the air or on the ground.

Whatever the case, it seems safe to assume that we’ll be seeing more of N8200L, as well as the other STAMP aircraft, flying discreetly over Libya, or perhaps other hotspots, in the near future.