Israel faces the jihadists in Syria, in Sinai and perhaps even at home…

From the military observation points overlooking the spot where Israel’s frontiers meet those of Syria and Jordan, Israelis can clearly see the positions of Liwa Shuhada al-Yarmouk—the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade. It is only one of many dozens of Syrian rebel groups, yet Israeli officers half-jokingly describe the fighters, mainly Syrians from nearby villages, as “Daesh lite”. The brigade, which may have between 600 and 1,000 men, has sworn allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the “Caliph” of Islamic State (IS), also known by its Arabic acronym, Daesh. The black flag of IS forms part of its logo.

So far, at least, the group has concentrated on skirmishing with the Syrian army and with rival rebel groups, and on securing its strongholds on the slopes of the Golan. But the Israelis are worried that, as IS is pushed back in other parts of Syria and Iraq, its leaders may decide to take over the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade and use its bases for attacks on Israel or Jordan.

IS has yet to attack Israel. Its main forces in southern Syria are about 80km (50 miles) from Israel’s borders. Last month, IS put out a recording, purporting to be the voice of Mr Baghdadi, saying that “with the help of Allah we are getting closer to you every day. The Israelis will soon see us in Palestine.” On January 18th Lieutenant-General Gadi Eizenkot, the chief of staff of Israel’s armed forces, warned that “the success against IS raises the probability we will see them turning their gun-barrels towards us and also the Jordanians”.

The most direct and likely avenue of attack is across Israel’s frontier with Syria. That is because the situation there is already chaotic; IS bases and civilian villages are close to Israel; and the terrain is mountainous. “A vacuum where no one is in control will always be the most dangerous location we should be looking at,” says a senior Israeli officer. Israel has toughened its border defences on the Golan, with new fences and sensors. It now stations regular forces there instead of reservists.

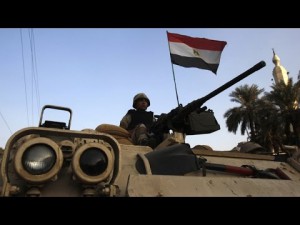

But IS may also choose other places from which to attack. Wilayat Sinai, which means the “Sinai province” of IS, has been operating on Israel’s western border for five years. It declared allegiance to IS in late 2014 and claimed responsibility for blowing up a Russian airliner last October, killing 224 people. But it is embroiled in a bloody insurgency against Egypt’s security forces. Israel, which is discreetly providing the Egyptians with intelligence and military help, says that IS shares routes for smuggling arms and other supplies with Hamas, the Islamist group that controls Gaza. These could be used for launching future attacks on Israel.

The Israelis are also worried that radical Palestinians who are citizens of Israel may be working for IS. So far they reckon that about 50 of them have gone to Syria to join IS. “There are more Swedes than Israelis fighting with Daesh,” says an Israeli intelligence man. Others say they are confident that Israel’s security service is better than its European counterparts at monitoring IS activity in its own territory. Even so, they fret that IS could become popular among young Palestinians in Israel, and in the West Bank and Gaza, where many are disillusioned both with the Palestinian Authority and with Hamas, its rival.

“IS is here and it’s no secret,” says Reuven Rivlin, Israel’s president. “I’m not talking about the borders of Israel, but about IS within. Research, arrests, witnesses, open and classified analysis all indicate clearly that IS’s popularity is growing and that even Israeli Arabs are actually joining up with it.” Vigilance along Israel’s borders may not be enough.

economist.com