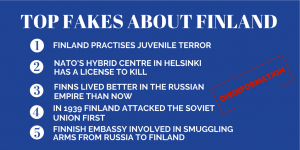

“We are at the Finnish Gestapo. Russia, help us.” “Finnish government’s policy against Russian kids – genocide or fascism?” And “Finland – a concentration camp for kids”, like reported by euvsdisinfo.eu.

These headlines are examples of Russia’s years-long, coordinated and persistent disinformation campaign targeting Finland. And this is a story of how Russia has over the years developed its capacity in influence operations, creating campaigns that artificially generate narratives to manipulate public opinion, and using a vast variety of channels, tools and policy instruments to achieve its goals.

Finland, an EU country and Russia’s neighbour with a 5,5 million population, is usually almost absent from the agenda of the Russian state controlled TV channels. Therefore, the peaks in the visibility are easy to detect.

To understand the motives of this disinformation, we need to step back in time.

It was in the autumn of 2012 – well before the war in Ukraine or the 2016 US elections – that Finland faced an information operation unseen since the collapse of the Soviet Union. For almost a month, day after day, all the Russian main TV channels followed the story of a Russian citizen living in Finland whose children the Finnish social authorities had put in an emergency placement.

In reality such a measure is only taken when the health or development of a child is in immediate danger were they to stay with their parents. But the coverage in Russian media suggested just the opposite: that children had been taken from their parents and put into prison without any reason, among other claims. Lists were shared with the media offering distorted figures of the number of Russian speaking children allegedly taken away from their parents and announced to be “victims of the Finnish fascism”.

Wide range of tools

Since 2009, these campaigns have come as waves, sometimes more frequent, sometimes less. The latest smaller campaign appeared at the end of 2017. The campaigns are not limited in making use of TV, which is one of the most powerful tools the Kremlin has in its hands to direct the flows of information space. They aim to politicise the issue further: Russia has attempted to raise the topic in the Council of Europe and has demanded that Finland set up a bilateral committee on the topic. Finnish pro-Kremlin propagandists have also played a central role in organising the disinformation campaigns, and even Russian diplomats have been involved, for example taking children from emergency care – without the permission of the Finnish authorities, which is illegal – with a diplomatic car. After the incident, the Russian ambassador was called to the Finnish Foreign Ministry to explain.

The motives and goals behind this disinformation campaign are various, and the same narrative has been used also against France and Norway. The goal seems to be about provoking tensions within the 75 000 Russian speaking community in Finland, by eroding their trust in local officials, which is traditionally high in Finland, and to test the resilience of Finnish officials, who according to Finland privacy legislation can’t publicly argue why an emergency placement has been necessary in a specific situation.

Another aim seems to be to wear down the overwhelmingly positive image of Finland internally in Russia. There it largely corresponds with the international rankings, which place Finland as having the second lowest inequality rates in the world among children and the third most secure childhood. Finland is also ranked as the second best country to be a girl in the world, the third best country in the world in adhering to the rule of law, and the best country in protecting fundamental human rights.

For years, Finland has been one of the most popular countries for Russian tourists to travel to. Last year it was the second most visited country after Turkey. But Russia seems to view it as in its interest to take some measures to limit foreign travel: After Russia annexed Crimea, reportedlymillions of employees of law enforcement offices were prohibited from travelling abroad. At the same time, Russia is heavily campaigning for domestic travel, especially to occupied Crimea.

Even if the TV and internet are Russians’ major sources for information, 18 percent of people still give most to first-hand sources: relatives and friends. Here the power of travelling steps into the picture: it is much more difficult to influence the opinions of people who have experienced the everyday reality of Europe themselves rather than perceived it from Russian TV.

In this context, Russia’s former children’s rights commissioner, the politician, celebrity lawyer and TV propagandist Pavel Astakhov, has called for declaring Finland a “dangerous country for families with children”.

Travel warnings and alerts are a common tool that is further used to disinform and to create an image of Europe suffering of moral degradation while Russia supports the “traditional family values”.

There is no reliable way to measure the impact of disinformation on actual holiday planning. But posts on Russian discussion forums still ask: Is it safe to travel to Finland with kids?

Building up defence

What has been the Finnish response to this and other disinformation campaigns that have now a stable position in Russia’s toolkit of influencing abroad?

It has been a combination of proactive public diplomacy and communication, relying on international agreements such as the Hague Convention, rejecting the idea to set up a bilateral commission, and treating the issue as part of the daily work of the local officials and experts, thus avoiding politicising it. Finland has reached out to reliable media in Russia and organised visits for the journalists to Finland, communicating the facts of the Finnish childcare system in Russian and stepping up the capacity to do so immediately when a new campaign starts.

And in 2014 Finland set up a network of government officials to address influence operations and started training officials. In 2016, the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE), open to EU member states and NATO allies, was established in Helsinki. This spring Finland appointed its first Ambassador for Hybrid Affairs.

The story of Russia’s disinformation campaign around the child disputes has revealed some of the mechanisms behind the spread of disinformation, thus in the end resulting in more awareness of pro-Kremlin disinformation both among journalists and the general public in Finland.

Meanwhile in Russia, according to a poll conducted by the Russian independent pollster Levada for the Finnish Foreign Ministry in 2017, 68 % of Russians describe their attitude towards Finland as “good”, the first things that come to their mind being sauna, Nordic countries, Helsinki, nature, high living standards and the welfare state.

55 percent of respondents had never heard of the child custody cases regarding Finland.

But 10 percent had heard a lot about these problems, and 26 percent had heard something but couldn’t remember any details.

So is 36 % a lot?

Overall these figures indicate that the disinformation campaign has not had a definitive role when Russians form their views about Finland. But when you put the figures into the context – when Finland in general has very little visibility on Russian TV, and when the topic would be non-existent were it not for disinformation – 36 % of Russians over the age of 14 years actually equates to 43 million people. That is quite a lot of people to be, potentially, basing their opinions about Finland on disinformation.