A military incursion ordered by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in the plains of Sinjar to thwart Kurdish rebels belonging to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) is stoking old tensions and prompting new questions over Turkey’s partnership with its Arab neighbours, like reported by middleeastmonitor.com.

“We said we would go into Sinjar,” Erdogan told Turkey’s Trabzon community on Sunday. “Now operations have begun.” Turkey’s confidence failed to convince officials in Baghdad. Under the “everything is under control” guise, Iraq’s Joint Operations Command (JOC) assured observers that no foreign troops had entered the country, contradicting Erdogan’s bullish statements in Trabzon. “There is no reason for troops to cross the Iraqi border,” the JOC insisted.

Turkey’s move centred on its self-assigned task to eradicate the scourge of PKK terrorism and rebel enclaves. This is a topic that representatives from both states have gathered today in Ankara to discuss.

The latest episode of the Turkish military advance and its entry into the northern Syrian town of Afrin last week represent the two dots that observers keen to understand the logic of such developments will inevitably join.

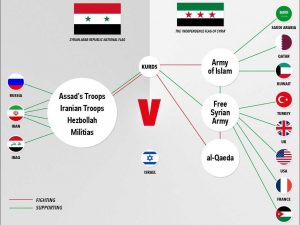

Erdogan’s need to curb the expansionist drive of PKK rebels in Afrin and now Sinjar is what the two operations have in common, though it is noticeably out of step with Turkey’s earlier reluctance about joining the Washington-led anti-Daesh coalition. Self-authorisation of more military operations is the path that Turkey has carved to defend itself, it claims, against the PKK and allies from the confederal party of Kurdish rebels in Syria, the PYD. The protection of Iraq’s minority Kurdish Yazidi community was the banner that has allowed some of these groups to settle more permanently in areas that they helped to liberate.

Turkey’s foreign policy manoeuvres therefore mirror a rather undecided or adaptive approach at best, following the conquest of Daesh across both spheres in June 2014. The siege of Kobani by the terrorist group that united rebel Kurdish forces was a scenario that replayed itself in Sinjar months later when the Kurdish Peshmerga enlisted the PKK’s help to expel Daesh. Since reclaiming the city in 2015, Sinjar sat firmly in the palm of Peshmerga forces until Iraqi forces took Kirkuk and surrounding plains following the post-referendum fallout late last year.

The wavering policies adopted by Erdogan’s government in Ankara prioritise the eradication of the PKK but are effective only when coupled with the military entrenchment of Turkish forces regionally. The cost is high but rewarding as far as Turkey is concerned when assessing the progress it has made in its three decade-long battle with the region’s Kurdish protagonists.

The meltdown of state authority and institutional decay in neighbouring Iraq and Syria has allowed these actors to grow taller, but the hour for Turkey to undertake what it views as necessary has finally struck.

It is feared that Mosul will be the next sphere into which Turkey may project its influence through military means. The post-2003 transnational Kurdish awakening is the reasoning that the government in Ankara has used to bolster its military capabilities. It is not the only one, though. The failures and inaction on the part of Baghdad to uproot Kurdish guerrilla fighters from its northern provinces is an oft-cited motive for foreign military action.

Baghdad walks a tightrope in this sense, building on the one hand a strategic partnership with Turkey whilst not shying away from accusing it of illegally invading parts of its oil-rich nation on numerous counts over the past three years. The rhetoric from Baghdad this time around, however, has been softened enough not to accuse Erdogan of trespassing.

The Sinjar tale has since evolved with incumbent Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi dispatching army brigades to replace PKK fighters ordered to evacuate, as local sources allied to the government claim.

Many predict that Turkey might revive the ghost of Mosul’s past, dreaming of its intervention against unwelcome Iranian-backed militia units, but the “blood and fire” with which sectarian enemies would flood the region, as Erdogan said in October 2016, has inspired moving words not military action. Cherry-picking its enemies may yield short terms gains but could cost Turkey some of its allies.

Turkey has done well to dodge the hostile bullets that onlookers and Turkey’s Kurd-sympathetic allies have fired its way due to Ankara’s policies towards Kurdish regional forces. What is certain, if the past decade is anything to go by, is that military victories — whether achieved by America, Iran or Turkey — are ephemeral if hearts and minds are not won.

What Turkey choses and the sides it seeks to win over will not be decided independently, but informed by the actions of regional chess masters and how they deal with the factions that Ankara opposes, which are hell-bent on moulding an independent Kurdish polity. Contradictions certainly abound in Turkey’s military incursions in both Iraq and Syria.