The Lebanese Army has ousted 600 Isil militants from the border with Syria, but the assault was only possible with multi-million dollar UK and US military aid, like reported by newstatesman.com.

In late August, the Lebanese Army (LAF) began the “Dawn of the Outskirts” operation to oust 600 Isil militants from 120 sq km of mountainous territory in Ras Baalbeck on Lebanon’s north-eastern border with Syria. Troops made signficant progress against the terror group, which had occupied the land since 2014. Less than 10 days later, Lebanon’s President announced the job done.

Embedded with Lebanese army troops, journalists were permitted entry to land retaken just days previously from IS militants.

Convoys of desert buggies, Humvees and pick-up trucks kicked up swirls of dust alongside burnt-out vehicles, which soldiers said had belonged to IS militants.

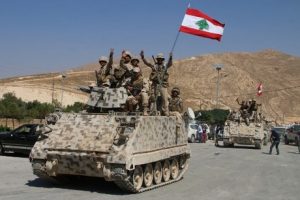

Troop morale appeared high as we passed groups lounging around their armed personnel carriers, flicking V for victory signs and posing in their battle vests.

“We hope they [IS] try to attack again so we can show them what we have got,” a senior ranking officer boasted.

The battle on this little-known front against IS – which is losing territory across Iraq and Syria – was mounted with multi-million dollar military aid packages from Britain and the USA.

An army source in Beirut told the New Statesman before the assault began that 90 per cent of the weapons in use were supplied by the USA, and UK-provided skills and equipment were essential.

Like most things in Lebanon, though, that is not something everyone agrees on.

The UK generally plays down its military involvement in the Mediterranean country, while the US is much more public. Earlier this month, it published a long list of weapons it had supplied to the Lebanese Army in the past year alone, including 50 automatic grenade launchers, 4,000 M4 rifles, and over half a million rounds of ammunition. Total spending in the past decade tops more than a billion US dollars.

As well as ousting IS, the operation saw the north-east area come under Lebanese state control for the first time. Up until now, it has been an unmarked border zone.

Training on UK soil, such as that described by the Lebanese soldier, has not been confirmed by British authorities. But substantial military aid from Britain is intended to keep Lebanon’s borders secure. The UK has been delivering a “train and equip” programme for Land Border Regiments, who oversee the north-eastern area. By April 2017, the Government had delivered 320 Land Rovers, 3300 sets of body armour, a secure radio communication network, 30 border watchtowers and over 20 Forward Operating Bases along the border, spending £61.5m.

All this has worked relatively well in creating a proper army out of what was once an ineffective and unorganised non-institution.

Lebanese soldiers are, naturally, defensive, when faced with the idea that they wouldn’t be able to cope without UK and US backing. Still, one soldier, who like nearly all troops deployed for the anti-IS offensive asked to remain anonymous, admitted things would be much tougher without it: “The help from the UK and US supports us. We would survive without it, but it would be harder and there would be many more dead and injured.”

Britain and the USA do not simply dole out military aid to Lebanon because they feel like it. It is a key way in which western governments hope to shape alliances in the Middle East. The idea in western policy is that a strong Lebanese Army will serve several purposes.

“The US and UK calculate that reinforcing the Lebanese state and its security apparatus will help Lebanon meet the successive challenges of Sunni Jihadi groups threatening to overrun the region,” says Middle East analyst Tobias Schneider.

The second idea is that a strong army – one of the few institutions that has cross-sectarian support in Lebanon – will lessen the influence and power of Hezbollah. The Lebanese political party’s military wing is considered a terrorist organisation by the UK and the US governments. That would contain Iran’s influence in Lebanon – Hezbollah is a proxy of the Islamic Republic – and reduce the likelihood of a new war with Israel.

But there is a problem in the west’s calculation that a strong army equals a weak Hezbollah.

“Hezbollah today being a pillar of Shia politics in the country, there won’t ever be sufficient political consensus in Lebanon for the army to directly challenge or confront the ‘Party of God,’” continues Schneider, referring to Hezbollah by its name in English.

Hezbollah has wide-ranging support and political alliances in Lebanon, stretching beyond its Shi’ite core to other sects. Lebanese convention dictates that the President must be Christian. The incumbent, Michel Aoun, is in power with Hezbollah support. Strengthening the Army will not eliminate the wide-held belief that the militia has a legitimate role as an anti-Israel force.

A staunch ally of the Assad regime in Syria, Hezbollah has played down the importance of foreign aid to the Lebanese Army.

Instead, in a speech this week in Baalbeck, a Hezbollah stronghold in the Bekaa Valley, Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah greeted an ecstatic crowd with the idea that defeating IS meant successfully foiling a US-Israeli plot.

“The US-Israeli plot in the region failed and the US-Israeli dreams that were put on ISIL and other terrorist groups fell”, Nasrallah told an audience of tens of thousands of people, who included girls screaming like fans at a One Direction concert. He spoke via video link, blaming security fears for his longstanding absence from public appearances.

Hezbollah draws supporters into the belief that “the resistance” – Hezbollah fighters – and an alliance with the Syrian Army are behind the Lebanese Army’s success, not the US or UK aid. On the same day that the latter launched the Dawn of the Outskirts operation, Hezbollah and the Syrian Army began an assault on IS fighters from the Syrian side. A week later, both parties announced ceasefires almost simultaneously.

That belief goes right down to the Lebanese person in the street, at least in some parts of the country. Outside the Baalbeck rally, 18-year-old Abbas carried an impossibly large yellow and green Hezbollah flag, and told the New Statesman, “The army needs the resistance and the resistance needs the army – they have a shared role”.

Hezbollah is proud of boasting its good relationships with both the Lebanese and Syrian armies.

That puts the Lebanese Army on rather a sticky wicket. They have been at pains to deny any such cosy relationship with Hezbollah, mindful of the threat that proof of co-ordination with a proscribed group would pose to its US-supplied dollars.

“In the current political climate, Congressional hawks could easily try and leverage collusion with the Iranian proxy militia and designated terror organisation into a full assistance stop,” says Schneider.

It has happened before: in 2010, the USA cut $100 million in aid after an incident on the Lebanon-Israel border.

During the Ras Baalbeck embed, Lebanese Army General Fady Daoud welcomed journalists into the operations room for the anti-IS operation. A journalist from Al Manar, the Hezbollah-affiliated Lebanese news outlet, asked what he knew about “resistance” positions across the border in Syria. Daoud, suddenly looking slightly flustered, gestured wildly at the scale model of Lebanon’s border territory in front of him. He insisted his forces were only dealing with land up to the border, and he had no information about positions in Syria.

The UK’s military aid programme for Lebanon is set to continue until at least 2019, by which time it will have trained some 11,000 troops. The embassy in Beirut declined a a request for an interview, but said in a statement that the UK is a “proud supporter” of the Lebanese Armed Forces. “We welcome the news that the LAF have been able to clear Daesh from Lebanese territory.”

But the USA, after making such enormous investments over the past decade, plans to cut its military spending on Lebanon next year. The Trump administration appears to want to abandon the long-held counter-Hezbollah strategy of strengthening the army, and tackle the group with sanctions instead. The former hasn’t worked because of Hezbollah’s entrenched support bases in Lebanon. The latter also risks isolating Lebanon and creating economic instability in a country where the government already fails to provide basic commodities such as electricity and water.

Nasrallah also has a point: while the Lebanese Army led the anti-IS offensive and denied co-operation with Hezbollah, it was a Party of God deal that eventually caused the Sunni militants to flee Lebanese soil. In exchange for information on the whereabouts of nine kidnapped Lebanese soldiers (found dead), IS was allowed safe passage from Lebanon to Deir Ezzor in eastern Syria. That caused another ruckus, leaving Iraq wondering why Hezbollah was striking a deal to place more IS fighters on its border.

In Baalbeck, the USA is not part of Lebanon’s stability – at least rhetorically. To a crowd repeating after him, Nasrallah hammers home Hezbollah’s ‘golden equation”: that Lebanon is safeguarded by a trilogy of “the army, the people, the resistance [Hezbollah].” There is no explanation that the “army” part of the equation would struggle without the USA. But it would struggle without Hezbollah too.