The Raptor is a fifth-generation aircraft that’s reportedly capable of destroying targets from 15 miles away with precision bombs.

Panoramica dei mezzi d'informazione islamici

In risposta ai raid aerei effettuati dagli USA e da cinque stati arabi alleati nella coalizione contro obiettivi dello Stato islamico (IS) e di al-Nusra, i jihadisti hanno inondato i social media (in particolare Twitter) condannando gli attacchi, lanciando un appello all’unità jihadista nella regione, e diffondendo minacce verso gli Stati Uniti e i paesi alleati .

A common talking point among jihadist and jihadist-supporting Twitter accounts has been that the U.S. and the West has declared war on Islam. The account of Dutch jihadist “Israfil Yilmaz” referred to the attacks as being delivered by “cowards from the sky” and followed up, “This is like Ive said before not just a war on State, but a war on Islam, a war on the Muslims of Syria and Iraq.”

The account of Rayat al-Tawheed, a media group of IS-supporting Western fighters in Syria, echoed the same message, tweeting, “The attacks are not just on IS but an attack on Islam.”

In the same tweet, Rayat al-Tawheed followed up with another prevailing concern among jihadist accounts, stating that the U.S. offensive “will unite the ranks and we will seek one of the two victories.”

Turkish user “Ahmed ibni Hasan,” made multiple tweets to the same point, stating:

Following this message, the user then tweeted:

Tweets making the same call for unity even addressed numerous Arab nations’ support for America. User “Ibn Ahmed” tweeted:

One jihadist, explained to be a fighter with al-Nusra Front, appeared in a video showing a building—allegedly an al-Nusra front headquarters—destroyed by U.S. airstrikes. In the video, titled “Verklaring Jagbhat al-Nusra,” he states that “many brothers died” and “got wounded.” He followed up, “Although things like this happen to us, we will keep on fighting the enemies.”

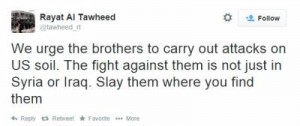

Other jihadist or jihadist-supporting accounts took a more aggressive tone to respond to the airstrikes, some implying or even directly calling for retaliation toward America. Rayat al-Tawheed, for example, tweeted:

Others tweets made the same threats to a snarkier note, with one user, “Abu Rayan #IS,” tweeting:

Jihadists expressed similar anger toward Saudi Arabia, which has openly declared support for attacks on IS by America. In an Arabic tweet, user ‘Al-Shaheedah# al-Khilafah” stated that if someone would provide him/her with a “bombed truck,” she/he would “pound airport of Tabuuk or any airport where their aircrafts take off from it.”

Another Arabic-writing user called for Muslims in Saudia Arabia to attack within its borders. The user, “Al-Jihad,” tweeted:

| L’ONU, l’Unione Europea e un gruppo di 13 nazioni hanno chiesto “un immediato cessate il fuoco globale” in Libia, dopo la missione delle Nazioni Unite che ha proposto – con inizio per la settimana prossima – colloqui tra i sostenitori dei due parlamenti libici rivali. |

In a joint statement, the group on Monday said that rivals must “accept an immediate, comprehensive ceasefire,” and “engage constructively in a peaceful political dialogue. There is no military solution to this conflict.”

The group of nations includes Egypt and the UAE, which were accused in August of launching and supporting air raids against militias controlling the Libyan capital Tripoli.

The call comes after the UN support mission in Libya, UNSMIL, proposed that backers of rival governments in Libya hold talks in Algeria – the first such negotiations since a surge of violence that began in May.

The UN mission said a joint Libya-UN committee would oversee any ceasefire, and urged rivals to agree a timeline to withdraw fighters from cities and key installations including airports.

The talks were proposed to start on September 29, the UN mission said.

Libya’s political scene is split between the Islamist-backed General National Congress in Tripoli, and its rival House of Representatives, which despite being internationally-backed is based on a converted car ferry in the port city of Tobruk.

The House of Representatives moved to Tobruk after fighters from ‘Libya Dawn’ took control of the capital and revived the GNC, which the House of Representatives was meant to replace after elections earlier this year.

The UN mission also called on militias in control of Tripoli to recognise the Tobruk parliament, saying the talks would be based on the “legitimacy of the elected institutions” and that they would also set the venue and date for a “handover ceremony” from the previous parliament to the one elected earlier this year.

Source: aljazeera.com

Nelle ultime settimane, vari segnali lanciati da Teheran e Riyad hanno alimentato le ipotesi su una potenziale distensione tra i due paesi: l’obiettivo sarebbe contrastare la minaccia presentata dallo Stato Islamico (IS), il gruppo radicale sunnita che dal giugno scorso ha fortemente destabilizzato l’Iraq e la regione circostante.

A seguito della caduta di Mosul all’inizio di giugno e del consolidamento di IS in Iraq ed in Siria, il governo iraniano ha intrapreso una serie di iniziative volte a creare un rapporto strategico bilaterale con l’Arabia Saudita. Il 17 agosto, Teheran ha inviato un nuovo ambasciatore a Riyad, rimpiazzando il diplomatico in carica con Hossein Sadeghi: è un personaggio molto noto ed apprezzato dai sauditi, dato il suo precedente mandato come ambasciatore durante la presidenza (relativamente riformista) di Mohammad Khatami, tra il 1997 ed 2005.

Il 26 agosto, l’assistente del ministero degli Esteri Hussein Amir Abdul Lahian ha visitato l’Arabia Saudita, per discutere, tra le altre cose, la posizione delle due parti sulla formazione del nuovo governo iracheno all’indomani dell’uscita di scena del primo ministro Nouri al-Maliki, che era stato precedentemente sostenuto da Teheran. A inizio settembre, il viceministro degli Esteri (con delega per gli affari dell’Africa e dei paesi arabi), Hossein mir Abdollahian, ha fatto visita a Riyad al Principe Saud al Faisal, ministro degli Esteri saudita: si tratta dell’incontro di più alto rango tenutosi tra i due paesi dall’inizio del mandato di Hassan Rouhani nell’agosto 2013. In base a quanto sostenuto da Abdollahian, l’incontro si è tenuto in un clima molto “positivo e costruttivo” ed ha avuto come tematica centrale “questioni di comune interesse”, ovvero la situazione in Iraq e possibili strumenti per combattere l’estremismo ed il terrorismo nella regione.

Il Principe Saud ha esteso l’invito a visitare Riyad alla sua controparte iraniana, Mohammad Javad Zarif, che si è a sua volta detto pronto a ricevere il rappresentante saudita nella capitale iraniana. Il 31 agosto, in una conferenza stampa, Zarif ha affermato che l’“Iran è sempre intenzionato a stabilire buone relazioni con i paesi vicini e l’Arabia Saudita è il più importante di questi stati, data la sua rilevanza per il mondo islamico e la sua influenza”. Zarif ed il Principe Saud si sono incontrati per la prima volta a margine dell’annuale Assemblea Generale delle Nazioni Unite, e hanno dichiarato che l’incontro costituisce la prima pagina di un nuovo capitolo nelle relazioni tra i due paesi, finalizzato a ripristinare la pace e la sicurezza nella regione.

Il presidente Rouhani aveva già tentato di dare una svolta alle relazioni con l’Arabia Saudita nel giugno 2013, durante la sua campagna elettorale: promuovendo un programma di politica estera volto al miglioramento dei rapporti con la comunità internazionale e con i paesi della regione, aveva sottolineato la necessità di dialogare con i sauditi. Nonostante l’ostilità reciproca degli ultimi anni, il Re Abdullah ha recepito in maniera positiva il messaggio di Rouhani, almeno formalmente, estendendo le sue congratulazioni al nuovo presidente iraniano. Tuttavia, di fatto i rapporti tra Iran ed Arabia Saudita non sono cambiati. Mentre Rouhani ed il suo gabinetto sono riusciti ad intensificare le relazioni con gli altri quattro paesi del Golfo, con numerose visite in Oman, Kuwait, Emirati Arabi Uniti e Qatar, lo stesso non si può dire per l’Arabia Saudita (e per il Bahrein, strettamente allineato con Riyad).

L’astio della Repubblica islamica nei confronti della monarchia saudita è endemico sin dai tempi della rivoluzione del 1979, in seguito alla quale Teheran identificò Riyad come un’alleata del Grande Satana, gli Stati Uniti. Il maggiore paese arabo della regione è stato anche visto come il bastione dell’Islam sunnita e di conseguenza come un rivale naturale. Con la morte dell’Ayatollah Khomeini nel 1989, le relazioni diplomatiche sono leggermente migliorate, dando modo alle varie amministrazioni che si sono succedute di avere un limitato margine di manovra nel determinare il loro approccio nei confronti dell’Arabia Saudita. Il periodo tra il 1997 ed il 2003, durante il governo riformista di Khatami, ha costituito l’apice del tentativo di riappacificazione tra i due paesi.

Le buone relazioni personali tra il presidente iraniano e l’attuale re saudita, e una graduale convergenza su alcuni elementi degli assetti di sicurezza della regione hanno portato ad uno storico accordo siglato nel 2001 per la cooperazione contro il terrorismo, il contrabbando di droga ed il riciclaggio di denaro. Al contrario, gli otto anni di governo Ahmadinejad hanno rappresentato il periodo più dannoso e caratterizzato da maggiore sfiducia ed ostilità tra Teheran e Riyad. Questo soprattutto dal 2011, quando lo scoppio della crisi siriana ha portando l’Iran a sostenere il presidente Bashar al-Assad, e l’Arabia Saudita a supportare i gruppi ribelli, alimentando la rivalità tra i due paesi e portandoli ad un conflitto indiretto tramite una guerra per procura nella regione.

Nonostante la minaccia presentata da IS abbia parzialmente riavvicinato Teheran e Riyad al momento e pur considerando che tale minaccia sembra costituire la priorità per entrambe, date le dinamiche regionali e la lunga rivalità, sembra pertanto difficile ipotizzare una cooperazione di lungo termine e di ampia natura tra le due capitali. Nonostante il temporaneo attenuamento del conflitto per procura tra Iran ed Arabia Saudita nei paesi della regione, i due si trovano su fronti opposti non solo in Siria, ma anche in Libano, Yemen e Bahrein, dove il conflitto ha natura settaria e si basa su interessi strategici fondamentali per entrambi i paesi ai fini del mantenimento di una posizione di potere nella regione. Inoltre, risulterà difficile per Rouhani creare un consenso interno nella leadership iraniana volta ad implementare una distensione di fatto ed una reale cooperazione con Riyad.

La convocazione del viceministro degli Esteri Abdollahian presso la Commissione di Sicurezza Nazionale e Politica Estera del Parlamento iraniano (il Majlis), per rispondere alle critiche mosse nei confronti della visita effettuata dal rappresentante governativo iraniano in Arabia Saudita, sono una chiara dimostrazione di ciò. I rappresentanti della Commissione hanno infatti sostenuto che “la visita non era necessaria data la posizione del paese ed il suo approccio nella regione”, caratterizzato da “un ruolo diretto nella creazione dell’IS e la cooperazione con gli Stati Uniti per raggiungere i suoi obiettivi”.

Le stessa accuse sono state reiterate dal rappresentante presso le Guardie rivoluzionarie del Leader supremo Ali Khamenei, che ha pertanto indirettamente escluso qualsiasi possibilità di cooperazione bilaterale. Gli ufficiali sauditi sembrano d’altra parte dubitare dell’effettivo potere di Rouhani e del suo gabinetto nel controllo e nella gestione della politica regionale iraniana, mossi dalla consapevolezza che tali questioni sono soggette per lo più alle decisioni prese dalle Guardie Rivoluzionarie e dalle Forze Quds, comandate dal generale Qassim Suleimani.

È dunque probabile che la distensione tra Teheran e Riyad rimarrà temporanea e limitata esclusivamente al piano della rispettiva retorica, mentre la fine della guerra per procura tra i due paesi nella regione, per quanto auspicabile, sembra per il momento soltanto una chimera.

Source: aspeninstitute.it

Nei giorni in cui la comunità internazionale, con Stati Uniti e Francia in testa, ha iniziato a mettere in atto la campagna per combattere l’IS (Stato Islamico) in Iraq e Siria, fonti di intelligence statunitensi hanno riportato di una nuova e più diretta minaccia all’Occidente, rappresentata da un altro gruppo jihadista attivo in Siria. Il gruppo si chiamerebbe Khorasan e sarebbe guidato da un terrorista legato al nucleo di al-Qaida centrale ancora presente tra l’Afghanistan e il Pakistan, Muhsin al-Fadhli.

A differenza dell’IS, con cui Khorasan sarebbe in competizione, l’obiettivo di questo gruppo jihadista sarebbe focalizzato a colpire obiettivi prevalentemente occidentali, come già avvenuto in passato in operazioni coordinate da al-Fadhli. Se confermata, la notizia proverebbe l’eterogeneità della galassia jihadista nel Vicino Oriente, oltre a testimoniare il fatto che al-Qaida è ancora attiva, nonostante abbia compiuto negli ultimi anni una sorta di ritirata strategica. Allo stesso tempo, gli Stati Uniti dovranno ancora una volta scegliere come agire in Siria, teatro che rappresenta il vero punto debole della strategia anti-jihadista di Obama.

L’allarme circa la nuova minaccia agli Stati Uniti, rappresentata dall’esistenza del gruppo Khorasan in Siria, è stato lanciato in un articolo del New York Times due giorni fa. Nell’articolo, si fa riferimento a fonti di intelligence statunitensi, e in particolare, si riportano le parole del capo dell’intelligence nazionale, James R. Clapper Jr., secondo cui “in termini di minaccia agli Stati Uniti, Khorasan può rappresentare una minaccia tanto grande, quanto quella dello Stato Islamico”.

Si sottolinea come, negli ultimi mesi, l’interesse è stato rivolto soprattutto all’IS, ma ciò avrebbe distorto la percezione del terrorismo nell’area. In particolare Khorasan, così come Jabhat al-Nusra (affiliata di al-Qaida in Siria) costituiscono minacce più immediate alla sicurezza statunitense. Il gruppo, il cui nome deriva dalla regione storica che comprendeva parte degli attuali Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tagikistan e Afghanistan, avrebbe le proprie radici proprio in Iran e, attualmente, è composto da jihadisti provenienti dal Pakistan e dall’Afghanistan, ma anche da alcuni Paesi occidentali.

Il leader del gruppo è Muhsin al-Fadhli, ex capo del network di al-Qaida in Iran. Già lo scorso marzo, la rivista specializzata di terrorismo The Long War Journal, riportava la notizia secondo cui al-Fadhli aveva spostato il centro delle proprie attività in Siria, in accordo con al-Qaida centrale e la sua leadership in Pakistan. Lo stesso al-Fadhli ha appoggiato l’appello di al-Zawahiri, numero uno di al-Qaida, contro l’IS, contribuendo a creare lo spaccamento tra il fronte qaidista e il gruppo di al-Baghdadi.

In Siria, Khorasan costituisce un gruppo di appoggio a Jabhat al-Nusra. Secondo le fonti statunitensi, il gruppo avrebbe legami anche con al-Qaida nella Penisola Arabica (Aqap), il gruppo affiliato ad al-Qaida attivo in Yemen. Di quest’ultimo fa parte Ibrahim al-Asiri, considerato il più importante fabbricatore di esplosivi della galassia qaidista: quest’ultimo elemento ha messo in allarme l’intelligence statunitense.

Proprio il supposto reclutamento di jihadisti europei, unito alla capacità di fabbricare esplosivi, sono fattori alla base dei timori statunitensi. L’ex vice-direttore della Cia, Mike Morell, ha confermato che molti membri verrebbero dal Pakistan e che l’obiettivo principale di Khorasan è quello di colpire con ordigni esplosivi obiettivi occidentali, soprattutto aerei di linea. Secondo Morell, il gruppo ancora vedrebbe gli aerei di linea come il simbolo dell’Occidedente e, per questo, ambirebbe a ripetere operazioni in stile 11 settembre.

Il connubio tra l’esistenza di jhadisti occidentali presenti in Siria, ma che potrebbero tornare in Occidente, e l’expertise nella fabbricazione di bombe, rappresenta l’entità della minaccia. Al contrario, attualmente l’IS sembra più concentrata a combattere la guerra sul campo in Iraq e Siria, piuttosto che a condurre direttamente attacchi contro l’Occidente. Associated Press riporta altre fonti di intelligence, secondo le quali Khorasan sarebbe in Siria proprio con l’obiettivo primario di reclutare jihadisti per gli attacchi all’Occidente.

Source: ISPI

I siriani preferiscono gli attacchi aerei americani e francesi contro i terroristi dello Stato Islamico oppure…

As a wary US Congress passed a resolution authorizing the Barack Obama administration to arm Syrian rebels against the Islamic State (IS), and as US military planners consider airstrikes against IS in Syria, Al-Monitor’s Syria Pulse covered how Syrians, suffering from more than three years of war, might react.

Khaled Attalah reports from Damascus that Syrians there prefer a political solution to the war rather than US airstrikes.

The National Coordinating Committee for Democratic Change in Syria rejects US intervention in Syria, even with the Syrian government’s approval.

Attalah writes, “After mobilizing its allies from around the world, the White House hopes that by using force and launching airstrikes, the IS threat will disappear. However, the Syrian people are not only hoping to be rid of this terrorist group, but also the bloody bottleneck they have been living through for more than three years.”

Reporting from the Al-Bab region, an IS stronghold east of Aleppo, Al-Monitor columnist Edward Dark writes that the prospect of US airstrikes is being greeted with more anxiety than enthusiasm, and could redound to the advantage of IS.

Dark speculates that “it would be foolish to believe that US military action against IS is popular here or will go down well, especially when civilian casualties start to mount. On the contrary, it will most likely prove counterproductive, stoking anti-Western resentment among the population and increasing support for IS, driving even more recruits to its ranks. The terror group knows this well, which is why it is secretly overjoyed at the prospect of military action against it. In its calculations, the loss of fighters to strikes is more than outweighed by the outpouring of support it expects both locally and on the international jihadist scene.”

In a separate report from Aleppo, Dark questions the wisdom and timing of an expanded train-and-equip approach to US- and Saudi-backed opposition groups.

“The failure of these groups to make substantial gains against the regime or the jihadists despite a large investment in arms, funds and training begs the question of what has now changed. If they were unreliable then, what makes them a viable option now? Not only were some of them merely unreliable, but they also openly collaborated and allied with al-Qaeda-linked groups such as Jabhat al-Nusra, or through sheer incompetence and corruption allowed Western-supplied weapons and equipment to fall into the hands of extremists. Indeed, the stigma of corruption and ineptitude permeates most of the Syrian rebel factions designated as ‘moderates,’ and some have even been involved outright in serious war crimes. This makes them not only an unreliable ally on the ground, but also a potentially very dangerous one.”

Dark observes that the moderate Syrian opposition groups are not close to winning “hearts and minds” in Syria. IS, while a bigger loser in the hearts and minds category, and despite its brutality, has nonetheless brought some degree of order and services to the areas it controls in Aleppo:

“The rise and popularity of IS seems to have more to do with the failings of the Syrian opposition and the fractious rebel factions than with the Islamic State’s own strength. For almost three years, the opposition and the local rebels had failed to provide any semblance of civil administration or public services to the vast areas they controlled. This lawless chaos added to the people’s misery, already exacerbated by the horrors of war. In the end, they rallied around the only group that managed to give them what they wanted: the Islamic State. But now, it seems a new fear is rising among the people: the specter of war against IS, a war they feel threatens not only their lives, but also their livelihoods and the tenuous normality they’ve grown accustomed to.”

Dark concludes that the most effective of all bad alternatives to defeat IS, which is the US priority in Syria, might be for the United States to reach a tactical understanding with the Syrian government:

“The only alternative then appears to be an unpalatable and unholy alliance with the Syrian regime, the only force on the ground right now capable of taking on and defeating IS with any degree of success,” Dark writes.

Kerry says role for Iran in battle with IS

While the Obama administration has ruled out an alliance with Syria, Iran could be a bridge to Damascus within an international coalition against IS and in a subsequent political transition in Syria.

US Secretary of State John Kerry, chairing a UN Security Council meeting on Iraq Sept. 19, said, “The coalition required to eliminate [IS] is not only, or even primarily, military in nature. It must be comprehensive and include close collaboration across multiple lines of effort. … There is a role for nearly every country in the world to play, including Iran.”

This column suggested in February that Iran and Saudi Arabia could join a new regional counterterrorism alliance among Syria and its neighbors, and in May proposed that the United States should test Iran on its declared willingness to battle extremists in Syria.

Ali Hashem reports this week that Iran has a vital interest in defeating IS, whatever the United States decides to do.

“Iran’s problem isn’t related to how and where to fight IS, but rather over the conflict between its national security and its regional security,” Hashim writes. “IS has had a base in Iraq — Jalawla — as close as 38 kilometers (23.6 miles) from the Iranian border, and Iran wants to get rid of the self-styled IS at any price. It doesn’t matter if this happens with the help of the Iraqi army, the Shiite militias, Lebanese Hezbollah, the Kurdish peshmerga or the United States, as long as there are results on the ground. A good example is the breaking of the siege around the town of Amirli in northeast Iraq. The operation was the result of US-Iranian indirect cooperation that ended with an obvious success. On the ground, pro-Iranian Shiite militias along with the Iraqi army advanced while US fighter jets bombed the IS posts.”

Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Hossein-Amir Abdollahian told Hashim that Iran isn’t “interested in taking part in any show-off conferences that claim to combat terrorism.”

“They [US officials] want to build an Iraqi army, train Syrian fighters and decide on whether they are going to strike inside Syria or not; meanwhile, Iran is fighting the war helping its allies, clear on the general strategy, and we know we’ll win in the end,” Abdollahian said.

SRF opposition forces still battling IS

Mohammed al-Khatieb, reporting from Marea, outside Aleppo, on the front lines between Syrian Revolutionary Forces (SRF) under the command of Jamal Maarouf and IS, refuted reports that the SRF had signed a nonaggression pact with IS.

Khatieb observed firsthand the deployment of hundreds of SRF fighters and interviewed SRF military commanders on their ongoing operations against IS.

Syrian government forces attempted to assassinate Maarouf, who is backed by Saudi Arabia, on Sept. 17, killing his daughter in the operation.

Khatieb writes, “The attempt on Maarouf’s life is a message from the regime to the United States that it will not hesitate to target US allies, after Washington snubbed the regime by deciding to fund the Syrian rebels in the fight against IS.”

Syrian Kurds under siege by IS

One of the most effective Syrian armed groups, the Syrian People’s Protection Units (YPG), is losing ground in the battle with IS forces in the Ain al-Arab (Kobani in Kurdish) region of Syria, the military arm of the Democratic Union party (PYD), forcing thousands of Syrian Kurds to flee into Turkey.

Amberin Zaman reports that US and international support for the PYD and YPG, which has support among Syrian Kurds, who number at least 10% of Syria’s population of 23 million, has lagged because of the group’s affiliation with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) of Turkey.

The United States considers the PKK a terrorist group, and Turkey has been unwilling to grant the PKK an edge in either its peace negotiations with the PKK or in Syria.

However, Zaman writes, “The PKK and the PYD/YPG are continuing their battle for global acceptance. In a move apparently calculated to provide the Obama administration with a fig leaf for future cooperation, the YPG recently sealed an anti-IS alliance with various groups affiliated with the Free Syrian Army (FSA), founding what they call the Joint Action Center. Its purported goal is to liberate all territories held by IS in Syria.”

IS has reportedly taken 40 villages from YPG forces in recent fighting.

Notizie di intelligence hanno avvisato Washington che lo scontro con lo Stato islamico può distogliere l’attenzione dei media da una minaccia, se possibile ancora più sinistra, proveniente da un gruppo terrorista molto meno noto ma potenzialmente molto più pericoloso, sorto dalle ceneri della guerra siriana.

Very little information is being released at the moment by anyone within American intelligence circles, but the group calling itself Khorasan is said by officials to have concrete plans for striking targets in the United States and Europe as a chosen modus operandi – more so than the Islamic State (IS), formerly known as ISIS.

The first ever mention of the group occurred on Thursday at an intelligence gathering in Washington DC, when National Intelligence Director James Clapper admitted that “in terms of threat to the homeland, Khorasan may pose as much of a danger as the Islamic State.”

According to the New York Times, some US officials have gone as far as saying that, while the Islamic State is undoubtedly more prominent in its show of force in the Middle East, it is Khorasan who’s intent on oversees campaigns in a way Al Qaeda usually is.

In this sense, the US air strike campaign and the coming actions by the anti-IS coalition might just be what coaxes the IS into larger-scale attacks on American and European soil – what Khorasan is essentially all about.

This brings up another issue seen in the current Western stance on terrorism: it is so focused on the terror spread by the IS that it’s beginning to forget that the destruction and mayhem of civil war across the Middle East is spawning a number of hard-to-track terrorist factions with distinct missions.

“What you have is a growing body of extremists from around the world who are coming in and taking advantage of the ungoverned areas and creating informal ad hoc groups that are not directly aligned with ISIS or Nusra,” a senior law enforcement official told the NY Times on condition of anonymity.

The CIA and the White House declined to give comment.

According to government sources, the Al-Qaeda offshoot group is led by a former senior operative – 33-year-old Muhsin al-Fadhli, reportedly so close to Bin Laden’s inner circle he was one of the few who knew of the 9/11 Twin Tower attacks in advance.

He had reportedly fled to Iran during the US-led invasion of Afghanistan. Al Qaeda’s story goes hazy after the campaign: many operatives are said to have traveled to Pakistan, Syria, Iran and other countries, forming splinter groups.

In 2012, al-Fadhli was identified by the State Department as leading the Iranian branch of Al-Qaeda, controlling “the movement of funds and operatives” in the region and working closely with wealthy “jihadist donors” in his native Kuwait to raise money for the Syrian terrorist resistance.

Although the first public mention of the group was only this Thursday, American intelligence is said to have been tracking it for over a decade. Former President George W. Bush once mentioned the name of its leader in 2005 in connection with a French oil tanker bombing in 2002 off the coast of Yemen.

Khorasan itself is shrouded in mystery. Little is known publicly apart from its being composed of former Al-Qaeda operatives from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia. The group is said to favor concealed explosives as a terror method.

Like many other groups taking up the power vacuum in war-torn Syria, Khorasan has on occasion shifted its alliances.

Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri at one point ordered the former ISIS to fight only in Iraq, but cut all ties with it when it disobeyed and branched out. The result was that the Nusra Front became Al-Qaeda’s official branch in Syria. It’s said that Khorasan is to Al Nusra Front what the latter was to Al-Qaeda.

When The Daily Signal spoke to James Phillips, a Middle East expert at The Heritage Foundation, he outlined some American intelligence views on the group: they see their mission in “[recruiting] European and American Muslim militants who have traveled to Syria to fight alongside Islamist extremist groups that form part of the rebel coalition fighting Syria’s Assad regime.”

“The Khorasan group hopes to train and deploy these recruits, who hold American and European passports, for attacks against Western targets,” he said.

He believes Khorasan to be Al-Qaeda’s new arm in attacking America, its “far enemy.” While they are Al Nusra’s allies in Syria, their role is believed to be to carry out terrorist attacks outside the country.

The group reportedly uses the services of a very prominent Al-Qaeda bomb maker, Ibrahim al-Asiri, whose devices previously ended up on three US-bound planes. He is known to be a true pioneer of hard-to-detect bombs.

Phillips believes that the next step is taking those bombs and pairing them with US-born and other foreign jihadists returning home.

In this respect, Phillips views the Khorasan threat to the US to be much more direct compared to the Islamic State’s more regional ambitions. And since President Obama’s upcoming anti-IS strategy reportedly does not include Al Nusra, this potentially frees Khorasan’s hands.

What sets Al Nusra apart from the many other groups is that it’s now the only faction with active branches throughout Syria.

Syria analyst with the Institute for the Study of War, Jennifer Cafarella, told the NY Times “there is definitely a threat that, if not conducted as a component of a properly tailored strategy within Syria, the American strikes would allow the Nusra Front to fill a vacuum in eastern Syria.”

Because of al-Zawahiri’s current weakened position in terrorist cricles, both Al Nusra and Khorasan by extension are less prominent than the IS. But these things have a way of changing unpredictably, and because the plans of these more traditional terrorist groups in Syria aren’t yet clear, a danger arises.

The volatile conflict zone that is Syria, with its lax borders and an increasing number of distinct, armed Islamist groups, the US may be surprised by how difficult it soon may be to pinpoint the origin of the next threat.

Source: rt.com

Precipita la situazione nello Yemen. I ribelli sciiti di Ansaruallah, che da giorni si scontrano con i miliziani sunniti filogovernativi, hanno preso il controllo della sede del governo e della radio di Stato a Sanaa nello Yemen. Fonti concordanti aggiungono che il premier Mohamed Basindawa si è dimesso per protesta contro il presidente Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi.

http://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/mondo/2014/09/21/yemenribelli-sciiti-in-sede-governo_42ce91bd-2d90-42af-bbaf-54305870388a.html