Al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was not assassinated in a cave in the Tora Bora mountains, nor in one of the villages of the no-man’s land straddling the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. The drone missiles hit his home in a “luxury” neighborhood in the heart of the Afghan capital of Kabul, not far from the former abodes of the U.S. and U.K. embassies, a borough locally dubbed “Thievesville,” after having become home to drug lords, mobsters and senior Taliban figures, like reported by haaretz.com.

It is unknown how long al-Zawahiri lived in the home that was destroyed early Sunday morning, but one thing is clear: The leader of Al-Qaida was a respected guest of the Taliban, just like the organization’s former boss, Osama bin Laden, who was assassinated in 2011. It seems that the surprise of Western pundits, particularly the Americans among them, was not so much at the assassination itself as at the “discovery” that the Taliban violated the agreement it signed with the U.S. administration, ahead of the American withdrawal from Afghanistan. In this 2020 agreement, the Taliban leadership promised that Afghanistan would not serve as a shelter for terrorists, nor a launching pad for attacks on the West. Such unexpected indecency and dirty dealing by the Taliban, an organization famous for its humane, liberal, human-rights-oriented approach, are apparently unforgivable.

Dr. al-Zawahiri, the 71-year-old Egyptian doctor who was Bin Laden’s personal physician and later appointed his deputy and then successor, has led Al-Qaida during the years when the organization developed into a decentralized corporation, holding autonomous branches throughout the Middle East, Africa and Asia. This was the new structure designed by Bin Laden after the 9/11 attacks on U.S. soil, which caused the invasion by a U.S.-led coalition of Afghanistan and later Iraq in 2003.

Bin Laden realized that concentrating all the leadership and control in Afghanistan was becoming much harder and riskier, and that he must create regional hubs that would not depend on a single headquarters. This decision led to the establishment of extensions in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Sinai and other places in Egypt, the Maghreb, and East Africa, each of which was placed under a senior commander. According to Bin Laden’s instructions, which were even committed to writing, the fighters were to mix with the local population, marry local women, open businesses and act like locals to blend in better and recruit fighters from the local populations.

One result of this decentralization was that local commanders created independent power bases that operated in two channels. In one, they placed their forces at the disposal of objectives set by Bin Laden and Al-Qaida, and in the other they acted against local regimes and competing Islamist organizations. Among his other duties, al-Zawahiri served as a coordinator and mediator between local commanders and the top command, headed by Bin Laden.

But his success in this capacity was limited. The most significant rift developed in 2005-2006 when the leader of Al-Qaida in Iraq, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, launched a local war against the Shi’ite community, alongside the large-scale terror attacks against American forces. In a meandering, almost obsequious letter sent by al-Zawahiri to al-Zarqawi in 2005, he explains that it is better to enlist the support of the Shi’ites for the establishment of a Sharia-based state, for without popular support Al-Qaida alone could not cope with the “enemy forces” and, at the same time, realize its strategy for the establishment of a Sharia state. Al-Zarqawi, who had already become the enemy of the Shi’ites and had also lost the support of much of the Sunni community in Iraq, rejected al-Zawahiri’s directive. Al-Zarqawi was killed in 2006 in a U.S. air strike, and it is suspected that an Al-Qaida operative, acting on orders from Bin Laden or al-Zawahiri, divulged his location to American informants.

But al-Zarqawi had time to pass on his teachings and strategy to Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, one of the founding fathers of ISIS, who was replaced upon his demise by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who became the enemy of Al-Qaida. Al-Zarqawi was not the only local leader to challenge al-Zawahiri’s authority, and in effect that of Bin Laden as well. In Yemen, al-Zawahiri also ran into a powerful opponent in the form of Anwar al-Awlaqi, who saw himself as a worthy successor to Bin Laden, and so it went in the North African branch as well.

But al-Zawahiri’s greatest failure came in 2014, when the immense success of ISIS, its rapid takeover of vast swaths of Syria and Iraq, and its murderous theatrics swept up tens of thousands of admirers in Islamic countries and the West, and emptied the local Al-Qaida branches of operatives. Branch after branch, from Sinai to Yemen to Afghanistan to Tunisia, deserted Al-Qaida and swore allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and ISIS. Al-Zawahiri was left with the fragments of an organization, his financial support fell sharply, and even his powerful Syrian arm abandoned him, establishing “Jabhat al-Nusra,” which changed its name to “The a-Sham Liberation Front.” Al-Zawahiri thus became the symbolic leader of an organization that had lost most of its prestige and status that had electrified thousands of Muslims around the world when, along with the Americans and Afghan Mujahidin, he had waged a successful war against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

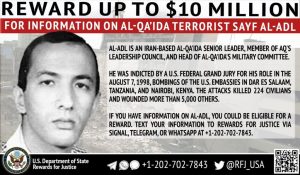

That said, the elimination of al-Zawahiri does not end the life of the Al-Qaida organization. The estimation is that the next leader will be Mohammed Salah a-Din Zidane, 62, known by the nom-de-guerre of Seif al-Adl. Zidane, an Egyptian who served in his country’s special forces and was arrested in 1987, was a confidant of Bin Laden who opposed the appointment of al-Zawahiri as second in command.

From all that is known of him, he is an explosives expert who participated in dozens of attacks against American forces, is broadly educated, speaks fluent English and is an authoritative organization man. Seif al-Adl apparently lives in Iran, under Revolutionary Guard supervision, and the question now is whether Iran will continue to host him or decide to expel him, should he indeed be appointed the leader of Al-Qaida.

The appointment of a new leader usually augurs an upsurge in activity, born of a desire to make a mark and solidify the position of the new leader. But new organizational initiatives will have to deal with the circumstances and conditions prevailing in a Middle East that has learned a few important lessons from its war against ISIS, with more experienced regimes, and with local militias that may oppose the local regimes, but are not necessarily allies of a religious ideological organization aiming to establish an Islamic caliphate.