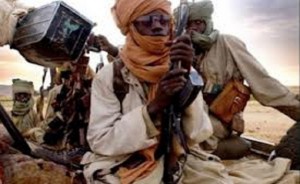

Militants linked to al-Qaida are broadening attacks across West Africa from their base in the desert to the coast. Their goal is to present themselves as the champions of resistance to France’s military in the region and prevent Islamic State’s expansion.

Two groups — al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and al-Mourabitoune — have claimed joint responsibility for assaults in Mali, Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast that killed more than 65 people, many of them foreigners, since November. The weekend attack on a seaside town in Ivory Coast was the first strike hundreds of miles from the Sahel, an arid region below the Sahara where French soldiers have been fighting militants since 2013.

The French presence in former colonies from Mali to Niger to Ivory Coast is being used by al-Qaida as a justification for its high-profile assaults on West African cities. The two groups recently reunited to compete with Islamic State, which has bases to the north in Libya and is trying to recruit fighters and expand in the Sahel, according to Mathieu Guidere, an analyst of Islamist groups in West and North Africa at the University of Toulouse II.

“Al-Qaida has changed strategy and is competing with Islamic State in the region,” Guidere said by phone. “They are presenting their actions as resistance to the new colonialist movement of France in Africa. There is a consistency in their attacks and this means that their fighters no longer want to leave for IS in Libya.”

France has deployed 3,000 soldiers in the Sahel following the seizure of northern Mali by Islamist rebels in 2012. Even after French fighter jets pushed them back, militants kept bases near desert towns like Kidal and regularly carry out hit-and-run attacks on United Nations peacekeeping troops. The UN says its mission in Mali has suffered the highest death toll of any of its operations globally.

Kidal is about 2,200 kilometers (1,367) miles from Grand Bassam, the site of this weekend’s attacks. That’s about the distance from Paris to Kiev.

Ivory Coast, the world’s biggest producer of cocoa, had been on high alert since November, when gunmen stormed into a luxury hotel in Mali’s capital, Bamako, killing more than 20 people. Authorities thwarted several militant plots before Sunday’s assault, Interior Minister Hamed Bakayoko said Monday. A mobile phone found at the scene should shed more light on the perpetrators, he added.

Even with increased security, it will be extremely difficult to prevent future attacks, said Bjorn Dahlin van Wees, an Africa analyst at the Economist Intelligence unit.

“The Ivory Coast attack was new in the sense that it was so far away from the core areas of these groups,” he said. “There’s certainly a risk of more attacks: they use simple weaponry, the borders are porous. Cities with a large western or French presence are the main targets.”

Analysts agree that Senegal is likely to be targeted next. Senegal, formerly the seat of the French colonial administration in Africa, has beaches that attract thousands of European tourists, as well as the biggest population of French citizens in West Africa, with 20,000 residents. The predominantly Muslim country has so far been spared militant violence.

Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb surfaced in the early 2000s as an offshoot from an Algerian militant group and gained notoriety through kidnappings of tourists in West Africa. It was based in desolate areas for years and appeared mainly interested in collecting ransom and smuggling in the Sahel, according to the Brussels-based International Crisis Group.

Today’s anti-western rhetoric from al-Qaida sympathizers is spread easily across social media, and sending more troops to patrol the region isn’t going to be effective, Guidere said.

“The combination of their expanding ideology and the anti-colonialist trend within the population makes it very difficult to stop militants from making these kinds of attacks,” he said. “You need a strategy to counter radicalization, an awareness campaign to explain to people why the French are there.”

stripes.com