Abu Qatada, who many have called the spiritual father of al Qaeda in Europe, is a scholar of Islam and what many might deem a terrorist instigator, or an ideologue who puts out arguments in support of militant jihad, but never himself fights jihad or spills blood. Yet, in these interviews, the third and fourth ICSVE researchers have made with him over the past year, he spoke candidly about his views on terrorism—making statements that will surprise many, like reported by eurasiareview.com.

Palestinian by birth, Abu Qatada grew up in refugee camps in Jordan, carrying within himself a heritage of bitterness over his lost homeland. He is angry and rebellious against what he believes to be Western hegemony. He does not hide his strong desire to see a fundamental reordering of the Arab world. In this interview, we spoke to him about the changes he longs to see in the Middle East and the guiding principles by which to influence such changes, including his predictions as to what might actually happen.

Earlier in his career, Abu Qatada resided in London, where he was editor in chief of the Usrat al -Ansar weekly magazine, a propaganda media outlet that he started on behalf of the Groupe Islamique Army’s (GIA). In the early 90s, Abu Qatada issued a fatwa, which was published in his weekly bulletin Al-Ansar, after the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) was poised to win elections in Algeria but was denied an impending electoral victory by a military coup. Some hold his issued fatwa against the military responsible for justifying GIA massacres against innocent civilians, including unleashing a rampage of beheadings. [1] In 2006, the GIA who Abu Qatada was aligned with in London, announced a union with Al-Qaeda, and by 2007 the group changed its name to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.

In 2000, Abu Qatada was deemed by the UK as a security risk and was arrested as a terrorism suspect, imprisoned and subjected to a secret parallel system of justice. He was held in Belmarsh Prison without a conviction, on and off for 10 years, under an emergency legislation that authorized indefinite detention of “certified” foreign nationals in the U.K. representing a national security risk.

Held with the aim of disrupting a network of extremist ideologues from promoting acts of violence in the UK, he was never officially and directly linked to any terrorist plots in Europe. A source close to the case, however, shared that intercepts of those who visited Abu Qatada revealed that they were later contacted and invited to meet others actually involved in terrorism, although nothing was ever found to directly implicate Abu Qatada.

Abu Qatada’s angry grievances and teachings against the West are believed to have inspired numerous al-Qaeda- related terrorists plots and killings, allegedly including, through second generation ties, the 2015 Charlie Hebdo massacres.

While a Jordanian court convicted Abu Qatada in 2002 in absentia on terrorism charges related to the thwarted millennium terrorist plots aimed at attacking Western and Israeli targets in Amman, such charges were overturned in 2014 on the grounds that evidence may have been acquired by torture. In 2013, after many delays, due to concerns that he might be tortured in Jordan, or again convicted on the basis of evidence taken under torture, Abu Qatada was deported back to Jordan. Already railing against the West and siding himself with al-Qaeda, Abu Qatada does not forget his time in Belmarsh. He is still angry over it, though, as we were able to witness, his anger profoundly resonates with a power of righteousness and moral superiority that must also affect his followers.

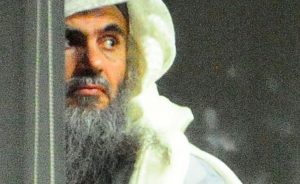

No longer in prison, Abu Qatada now resides in his stone hewn home on the outskirts of Amman, Jordan. Dressed in a long dark thobe and his grey beard reaching over his chest, he hosts us in a large diwan, with its walls filled with collections of books—translations of histories and philosophies from around the world, and books about Islam. Surrounded by towering shelves supporting hundreds of such books, mostly in Arabic, one could not help but be drawn to the “intellectual warmth” we sensed, including the room’s distinct touch and setting that offered a glimpse into Abu Qatada’s character, interests, and passions.

During our two days of conversing with him, he covers a whole range of topics and makes numerous statements. The most surprising to us, however, is that Abu Qatada, the supposed terrorist instigator, does not appear to support terrorism at all. Despite expecting armed conflict in the Middle East and hoping for the demise of regional dictatorships and the rise of an Islamic State of sorts, he strongly condemned the use of terrorism.

This is our third time talking to Abu Qatada and we already know he is a fervent advocate of the Palestinian cause. Speaking about the defensive posture he feels he was born into, Abu Qatada states, “We [Palestinians] have only one choice. [We were] forced to take one choice of adapting to a reality on the ground. If you are put in the corner, you have to scratch out to defend yourself.”

Having witnessed the Palestinian-Israeli peace process fail repeatedly, he is also cynical. “I’m very afraid of the word peace, because it’s the word most used by the oppressor,” he says. Furthermore, he adds, “You talk about peace after you take your rights…you are not given rights, through oppression. For the Palestinian, regardless of other identities, ‘peace’ is not in his interest.”

“Twenty-five years ago, when they told us the word ‘peace,’ they presented it to us as hope, but now after the experience of ‘peace,’ we found out it is a lie. Now, when I hear the word ‘peace,’ I hold my pocket, for the new theft going on, ”Abu Qatada says with a smile crossing his face.

“Beautiful things are only built with strong foundations,” he explains. “When you entered the house, you saw the book shelves and chandelier, but didn’t see the foundation that is represented under the stones. You can’t talk about dialogue without a fundamental basis.”

“Principles?” I ask, eager to discuss this very thing, as we want to hear where he stands on the principles underlying terrorism.

“No, before principles, it’s rights,” Abu Qatada answers.

We discuss Trump and his recent recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, while we wait for the opportunity to ask him about how he justifies Palestinian terrorism. Using the example of Wafa Idris, the first female suicide bomber whose surviving family members I interviewed in 2000, I tell him about my visit to her family and ask him about Wafa’s attack on civilians. A number of Palestinians I spoke to at that time told me, “We have to use our bodies to fight back against a much better armed force, to explode ourselves to equalize the battle.” But she exploded herself among civilians, in a shoe store. Do you agree with this?” I ask.

“To talk about details distracts!” Abu Qatada answers, with his face reddening in sudden fury. “To take the whole Palestinian issue and to drill down to such details!” he sputters.

“But it’s not details, it is the principle behind details. Is it correct to say that if I’m fighting a much stronger enemy I can attack children, for instance?” I ask.

“No, this is not accepted,” Abu Qatada responds, still unable to avoid the barrage of angry expressions showing on his face. “But I am not talking about people talking with their emotions,” he continues. “I am Abu Qatada talking from a scientific [i.e. religiously defended] position. This I will not allow it. I consider it a destruction to the issue that I believe in.”

He goes on to tell me that Wafa Idris was acting from emotions, and that we cannot possibly know the depth of pain for what motivated her to engage in suicide bombing and target civilians. Indeed, having interviewed her family members, I know her story intimately. I know that she served as a nurse on Fridays with the Red Crescent during the Second Intifada and witnessed countless casualties from demonstrations against the Israelis. For instance, shortly before the suicide bombing, she was helping to transport a man whose skull had been fractured by Israelis. Her job was to hold his skull together as the ambulance bounced over rough Palestinian terrain, but she ended up with his brains falling out into her hands as he died. Her brother stated she was never the same again.

While Abu Qatada might not necessarily know all the details of her story, he does not have any trouble imagining them.

“This attempt to enter details to discuss the moral reality of the fight from our side, it is like a denial, a journalist denial,” he practically shouts, as he stands up now. “Like being mad at a child under the boot of a solder because he doesn’t have the right appearance, ” he adds. His face is now red with anger, and I wonder if our interview will be abruptly terminated. I wonder if I have touched a raw nerve of Abu Qatada or trampled upon what he views as the Palestinian right to fight back, even using terrorism as a weapon.

“Definitely Wafa Idris was mobilized by her emotions and her anger,” he continues, calming somewhat. “The question should be why a young girl’s emotions would be moved to this extent.”

That is a powerful and meaningful statement indeed. Having traveled throughout the West Bank and Gaza during the second Intifada, I know what it is like to be mistaken for a Palestinian woman and hauled out of buses at Israeli gunpoint or nearly run off the road by Israeli Humvees. It is a constant feeling of threat with no rights, except in my case when I presented my American passport. Then everything changed—for me at least.

“I know my mother, my wife, my daughter. I know how they think. I know what mobilized her. A human emotion that should not be discussed ideologically,” he continues.

“I was in her home,” I counter. “Her nieces and nephews were playing beneath this giant-sized poster glorifying her and her act. Do you think that’s the right thing to do?” I ask, trying to draw him out on the principles of the battle for the things he wants most in life and for which he is willing to encourage others to fight.

“To consider her an icon within her society just because she represented the anger,” Abu Qatada sputters again. “It’s not whether she went into a shoe shop or a military camp,” he states. Piercing me with his eyes and standing tall in his dark thobe, he gestures with his hand warning me, “I’m angry now.”

That was already obvious, but he has put it out there, so I try to calm the situation, keep him talking, as I want to know what he really thinks.

It does matter if it was a shoe store frequented by civilians or a military camp—that is the heart of the matter. I want to hear him address it, but we will not get there if he abruptly ends our interview.

“If we brought the Muslim world, not just the Arabs, and put them on a scale and compared their deeds to the deeds of the Westerners,” Abu Qatada states. “And talk about history. How many people did you kill? How many bodies did you bury?”

The argument amounts to what I often heard all through my time in Palestine: that the Israelis killed civilians at a much higher rate than Palestinians killed Israeli citizens. The question I always countered with was whether the Israelis specifically targeted Palestinian civilians, as the Palestinian terrorists targeted the Israeli civilians? The answers were often vague: that Israelis did not aim for civilians but when they targeted their enemies they knew full well that they were killing civilians as well, and in high numbers, and still did not refrain from carrying out their acts. “So, what is the difference?” the Palestinian terror leaders would ask me and that would be our stalemate—perhaps to be repeated here as well.

For me the difference between targeting civilians vs allowing for collateral damage is important, although one could argue that the moral difference between the two can become slim indeed. When premised upon the right to live a full life, the morality of killing innocent human beings becomes unjustifiable in both scenarios, but is still much different when the intention is to kill innocents versus acts aimed at heinous criminals in which innocents also get killed. Nonetheless, these issues have troubled many even former Shabak (Israeli Security Agency) leaders who discuss these very points as documented in the 2012 Israeli film, the Gatekeepers.

“These are the guys, these are the Jews, who went into villages and massacred them—the Egyptians, slaughtered them with kitchen knives,” Abu Qatada states referring perhaps to the Rafah and Qibya events.

“Then you come to a society, you don’t know how a young girl in our society can…” Abu Qatada booms, but his voice trails off, overcome with emotion. “I am a man, I am an extremist, a terrorist, but I cannot explain Wafa. On a human level, I don’t understand what mobilized Wafa. But, the explosion of emotions and the anger I can understand,” he states, his eyes blazing, still towering above us.

“The pain, people do things that cannot be understood ideologically,” he continues, as I recall him telling us in the first interview that he feels the pain of his lost homeland every day. The gnawing bitterness inside. “I am not going to apologize for what she did.”

We talk a bit about the recent recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, and as we talk politics, Abu Qatada sits down again and calms himself down.

“Those barbaric settlers have no values,” he states. Suddenly, the conversation veers into the issue of settlements and my unpleasant experience way back at a checkpoint in Nablus with settlers supported by Americans. I shared my fear and anger when Israelis pointed guns at my face, including my feeling of disappointment and temptation at the time to remind them that “my tax dollars probably paid for the rifles they pointed at me.”

“I don’t hate very many people, but I hated them,” Abu Qatada states, clearly glad to hear that I also did not think well of the settlers’ misbehavior at their checkpoint. “They take from Americans the weapons,” he continues. “Everyone knows that a solution would come if America disengages from Israel.”

I try to steer the conversation back to the discussion on principles. Which principles does Abu Qatada stand by when he advocates for fighting back to win back Palestine, to bring down corrupt and unrighteous governments in the region, or to bring his hoped-for ideal of an Islamic state in the Middle East? I tell him how the Palestinian terrorist leaders I spoke to in the West Bank and Gaza would argue that it was permissible to kill Israeli civilians, even children, because they all eventually end up serving in the military—that Israeli society is militarized with the aim of keeping Palestinians down.

“I told you from the start, religiously I oppose the idea of killing children and all civilians. But I understand the emotions. Israel is a militarized society, but it does not justify killing children.”

“I cannot understand, not just psychologically but religiously also, how could anyone justify killing a child,” he states unequivocally.

“We are talking about when we can control the battle,” he adds, and I nod.

“Throughout history, Westerners were the ones who first started using civilians to put pressure on soldiers,” Abu Qatada explains, citing various examples from history. “ Even Hitler, they used civilians to pressure soldiers to submit,” Abu Qatada argues.” If there were those [civilians] affected by us, they were more affected by the West. We never used [killing] civilians to pressure as a strategy.”

I ask again, as I’m surprised to learn that Abu Qatada’s views seem to stand in stark contrast to those of other Palestinian terrorist leaders I spoke to in the West Bank and Gaza. They justified terrorist killings of Israeli citizens by arguing that Israeli men and women are part of the military—arguing that even their children who will grow up to serve. They also argued that Israelis have modern equipment while Palestinians have only their bodies to explode in terror attacks. None of this sways Abu Qatada from his clear denunciation of terror attacks against innocent civilians, particularly against killing children.

“I am surprised that there is any Islamists who will support it,” he says. As we have spoken for hours at this point, he tells us we need to adjourn the interview until two days later.

When we return, Abu Qatada begins the interview telling us that he told his wife about our discussion on suicide terrorism aimed at civilians. The topic has clearly caught his attention, and he has been brooding on the subject.

“From that day to today, I have been thinking how can anyone with feelings issue a fatwa of killing women or children outside of the battle, I honestly ask you?” Abu Qatada asks, his big brown eyes sincerely gazing into mine as he speaks.

I have been thinking about it as well and am ready to list Palestinian leaders for him who justified killing innocents using suicide terrorism. Khaled Mashal [the leader of Hamas] and Ahmad Sa’adat [the General Secretary of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, PFLP, an organization that engaged in terrorism], we mention for starters.

“Who was Hamas following?” Abu Qatada asks.

When I tell him that Sheik Yassin supported martyrdom operations against civilians during the second Intifada, Abu Qatada answers that Yassin did not have the ability to issue a fatwa of this type.

“Fiqh [Islamic jurisprudence] doesn’t deal with things like symbols,” Abu Qatada explains. “In the sharia [Islamic law derived from the Quran and Hadith], there is a big difference between targeting civilians and targeting a military man, as with collateral damage, trying to reach a military target and the consequences of reaching a target.”

“No one announces that they target civilians, like the Russians did. This is not the act of a person of resistance or of ideology. This is an act of revenge. I cannot imagine an Islamist or a Palestinian who does this,” Abu Qatada states with what appears to be full sincerity, as I wonder where he was during the Palestinian second Intifada, when Palestinians were engaged in suicide bombings in crowded Israeli restaurants, nightclubs, and grocery stores. I find his stance on the issue surprising to say the least.

“I really thought about our talk,” he continues, appearing disturbed. “The people inside [Palestine] are more aware of things than me. They look at every [Israeli] man and woman as a military person. Israeli society is a military society. They look at the Jewish guys in Palestine as military guys.”

“I cannot imagine going against children,” he repeats.

What about beheading journalists like ISIS has done in recent years?” I ask, curious to know if he is willing to condemn such acts as terrorism as well.

This gets us off on a discussion of whether journalists are who they say they are, as Abu Qatada references what he calls, “the dirty work of the CIA.”

“[What] if you catch someone who says I’m one thing and is something else?” he asks. Yet, ISIS has assassinated numerous journalists who were highly unlikely to have been spies, James Foley being one of them, I tell Abu Qatada, also mentioning that I have met and spoken to his bereaved mother in person, hoping this human element will make him feel the horror of it.

“You judge a journalist as you judge a messenger,” Abu Qatada answers. “A messenger is never to be killed. But if there is a journalist who is really a soldier, he will be dealt with as a soldier.”

I press him on the journalist James Foley and Nicholas Berg, both beheaded by terrorists (ISIS and al Qaeda) in Iraq.

“I don’t know this issue. I didn’t study this issue,” Abu Qatada answers. He appears sincere in what he is saying. Perhaps he is so buried in his religious and political studies that he just blanks out all the violence carried out by those on his side?

“I understand the grudge and bitterness that is carried against the Americans,” Abu Qatada explains, kindly excluding me from that hatred, which makes me wonder if sharing my many experiences of being mistaken as a Palestinian in dealings with the Israelis in the West Bank and Gaza, and how I, too, felt under threat and sometimes felt the urge to fight back has somehow softened his heart these days when he is talking with us, or is this how he normally feels when it comes to terrorism. We are two women talking to him after all, I wonder if he is showing a softer side on these days for us, but it is not how he really feels? But it does not seem that way, as he continues to repeat himself.

“You can never kill civilians intentionally,” Abu Qatada stands firm in his statement. “Our battle is not with civilians. This is an indisputable rule.”

“Why do people around the world think you say something else?” I ask, dumbfounded to hear him disavow terrorism.

“No one has interviewed me,” Abu Qatada answers a smile crossing his face. “I expected to sit with you once only. Most come only once,” he states. This is our fourth time visiting Abu Qatada. With each visit, we have ensured that we do not overstay his welcome, but have talked with him for hours. Although considered the spiritual father of al-Qaeda in Europe, I cannot underestimate his wide range of knowledge on the most pressing global issues, not to mention his intellectual potency and immutability in character when it comes to narrating the story of human suffering, particularly as it pertains to Palestine and the Palestinians. He is clearly well read, follows politics closely, and has a fire inside for justice: “No one has heard of me and sat with me, except [when] he was stunned by what I said,” Abu Qatada explains as his friendly smile covers his face. “It’s a big propaganda [about me], ”he adds.

“Many reports credit you as having issued a fatwa to kill civilians in Algeria,” I say, letting the harsh words come out between us like the wood table that separates us as we talk. I am afraid it will anger him again, but better to get it all out in the open.

“What I said was…if the Algerian army used our women and children to pressure our fighters, the mujahideen are allowed to use the threat of killing their women and children, if they continue in this way,” Abu Qatada explains. “It was a battle to stop the ugly way of killing civilians if this battle continued. On this message it would not have continued,” he explains. “It was the reason to stop an ugly battle going on.”

“If the only way I can stop your killing my wife and children is by threatening to kill your wife and children, then so be it,” he explains, looking exacerbated at this point. “The reality of this fatwa was not to open the door to actual killing of women and children,” he explains.

“Sometimes a surgery will take you 15 minutes to do but will give you rest for the rest of your life,” Abu Qatada says, suddenly feeling defensive. He is obviously disturbed knowing that he many have repeatedly blamed him for the carnage that resulted after his fatwa was issued. It appears it was not his intent, as our conversation today indicates.

“My picture is an atom on the head of a needle compared to bombs dropped on a city to stop a war,” he says, while remaining defensive. “Were the Japanese killing women and children for the other side to threaten them?” he asks, and continues, “There is a difference between threatening to kill innocents and actually doing it.”

I decide to ask him what I asked Ahmad Sa’adat in a prison interview with him during the second Intifada, telling him to imagine I am dedicated to the “cause.” “I want to go bomb myself in Jerusalem for al Aqsa, will you give me your blessing?” I ask.

“No I won’t give you my blessing. I won’t give my blessing to kill a clear civilian,” he answers, again unequivocally and without hesitation denouncing terrorist acts aimed at innocents.

“Do you remember when the Palestinian groups started hijacking planes?” he asks. “ Wadie Haddad, [the Palestinian leader of the militant wing of the PFLP] was the architect. He was with George Habash [the founder of the PFLP]. They asked him why he was doing this? I want the world to hear the Palestinian message,’ he answered.”

“In this thing now,” Abu Qatada asks, “What will a civilian target accomplish for me now?”

“Even when the military targets a civilian target, it’s a loss from a military perspective,” he adds.

“So, 9-11, was it wrong?” I ask.

“I went to prison for 11 years because I answered a question that wasn’t right,” Abu Qatada fires back, referring to his time in British prisons. “I don’t like my answer to look like I want sympathy from Americans,” he demurs.

“If Hamas did something against civilians, if they went to a religious kids school [to attack it], is it up to me to condemn or to be hung?” Abu Qatada asks, placing the responsibility back on the group.

“There is an area of agreement between us, and all Muslims: that it is not allowed to kill women and children,” he explains. “We all agree on this, but in any dialogue, someone will come and tell me, I did this in different circumstances. This is a sub dialogue and could create an exception,” he states. Referring to when there are disagreements on exceptional cases, he adds, “This disagreement that will come out would not make me go towards my enemy. At the same time, to be honest, I will have no sympathy for my opponent. I cry for my family, my people.”

He further explains that it is important for him to show solidarity for his own people. “The sheiks, because of their positions, from certain times, they started sympathizing with the opponents of the nation; they went against those in the ummah who fight their enemies,” he explains. “I will not go against anything an Islamist did,” he adds.

“So you will not go against ISIS?” I ask.

“My problem with ISIS is that they killed Muslims,” Abu Qatada explains. “And I never said anything against them when they killed Muslims, he adds, reflecting how he doesn’t like to break ranks even when he fundamentally disagrees with [such] tactics and principles.

“My priority is my nation,” he continues. “I always want to be in sync with their feelings. I am not willing to upset Hamas or the mujahedeen in exchange for hand clapping by the West.”

I can see his point, but ask him all the same. “Does not a person of principle have to have his principles and openly state them?”

“My principle is to be on the side of my nation. If a Palestinian is listening to me saying I condemn the killing of James Foley, then what is this in comparison to what Human Rights Watch documents?”

I tell him that I see resemblance in his response to what Shamil Baseyev, a Chechen terrorist, admitted to a journalist after over 300 schoolchildren and their parents were killed in the 2004 Beslan siege. While he grudgingly admitted to being a terrorist in that interview, he also demanded that the journalist add Putin to his terrorist list, as an even worse terrorist, as Basayev killed over 300 while Putin killed 40,000 civilians in carpet bombing the capital of Chechnya. “Yet, his terrorists shot those children in their backs as they tried to escape,” I point out as Abu Qatada reaches out to his toddler granddaughter who has entered the room. She is adorable, with curly dark hair and a red dress.

“To take them as hostages to use them,” Abu Qatada states, referring to the Beslan children, then kisses his granddaughter on the head as she passes by. “There is a difference between using and killing the children,” he concludes. “I will be guilty if I show compassion,” he adds.

“But, is there right and wrong?” I press as my heart breaks that we are discussing such things while he is kissing his grandchild so sweetly.

“With my words, I cannot simplify 99 rights and concentrate on one wrong.

It will condemn all 99 rights,” Abu Qatada explains. “They [Westerners] will use our words against us,” he warns, while admitting, “We do have an internal debate, and it’s known that I don’t handle these debates.”

I remind him of how mercilessly the terrorists shot the children while attempting to flee the school during the Beslan siege. His granddaughter is running around our table as we talk, and I cannot wipe from my memory, while gazing at her pure innocence, the images of the bereaved parents I talked with—whose children had been killed there and the traumatized siblings who survived when their brothers and sisters did not.[ii]

“I’m 58 years old and I learned how to resist my emotions, even when I see a documentary of what happened to my opponents,” Abu Qatada answers. Everyone is sympathizing with our opponents. No one is sympathizing with us. I understand. You, as an American, want to be just in distributing your sympathies, but me as a Palestinian, I visit my father every two weeks, and he cannot sit with me once without talking to me about Palestine.”

“Sympathy is not the same as principles,” I press.

“I don’t own a media podium that will be equal to what my opponents have when I talk about the pain of my nation,” Abu Qatada explains. “But when I talk about what my brother does, the whole world will listen to it and use it? Which is about something that is right but reaches a wrong. You should not [judge] as the act itself but the end itself.” While what he is saying might read as “the end justifies the means”, he does not quite mean that. He proceeds to explain that he is referring to the possibility of his standing up for principles being used to delegitimize what he holds sacred, such as the Palestinian struggle, or the Muslim/Arab struggle, for that matter.

“When my word is being used, whether in right or wrong against my people,” Abu Qatada explains, while temporarily halting his speech. “I saw how people who made this type of mistake and were coopted into the fold of the opponent, whether they meant to be or not. We have a saying: don’t hang your dirty laundry outside. Don’t do that especially now, when we are at the point of weakness. He goes on to explain that he does not want his words condemning attacks on civilians to be twisted against the Palestinian or the greater Muslim struggle, especially when he feels that instead of his call for a reordering—even if by armed struggle, if necessary—to bring justice to both, only that particular sound bite will be extracted from his many statements,

“Once I am able to reach out my word to the nation’s enemies in the same strength as my opponent is using against my brothers, then I can speak out,” he comments

“It’s not a question that just happened now,’ he continues. “The whole time I was in prison [in the UK] it was the same. I could have gone out in public and condemned 9-11… and become a hero, well known…and obtained UK nationality, among others. I didn’t accept it. It would be a betrayal.”

“When a nation is in a battle, you must balance what you should and should not say,” he metaphorically encapsulates his reticence to publicly condemn terrorism at this point in time. “When things are more relaxed, it’s the time to talk. It’s dumb to give your opponent a weapon,” Abu Qatada concludes.

Drinking coffee together, we end our chat with Abu Qatada. We drive away trying to make sense of the so-called spiritual father of al Qaeda in Europe apparently being against attacks against innocent civilians or terrorism essentially. We wait to hear if he will deny having said it or quietly accept his words in print—hopefully not used to harm the legitimate bases of his cause in any way.