Even to those who have hunted him and followed his every move, Islamic State (IS) Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi remains a mystery.

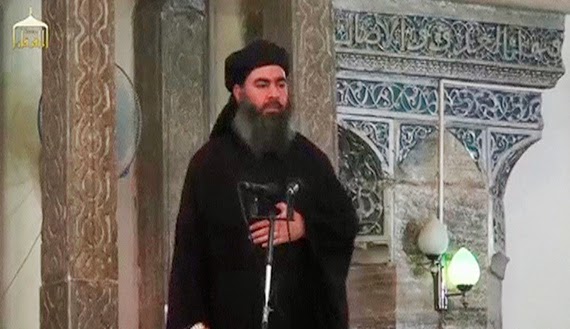

Iraqi forces had him in their crosshairs on Nov. 8, 2014, but an airstrike came too late and a wounded Baghdadi, 44, managed to slip across the Syrian border. The self-styled caliph now travels secretly and has avoided the public eye, apart from his infamous Friday sermons at a mosque in Mosul. While seclusion has only raised his profile, Baghdadi’s origins remain wreathed in more mystery than his movements.

Uncovering the man behind the demagogue was no easy task, so to find an answer I interviewed people who met him, saw him or lived with him in the past. I visited the neighborhood where he lived in Baghdad and the mosque he led the prayer services as an imam; I saw pictures of his family members, including his sons, daughters, brothers and wife. Based on all this, I will try to depict the man before he became the elusive Baghdadi, when his name was Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai, or Sheikh Ibrahim, of Samarra and he led a fairly normal life.

How did Sheikh Ibrahim become Caliph Baghdadi?

This was the main question to answer. The first place to visit was the neighborhood of Tobji, nestled in northwest Baghdad, where he lived and was the imam of the Sunni mosque of Haji Zeidan, built in 1958.

“People here are afraid of discussing this issue openly,” Khaled said. “My father has been arrested several times because of Baghdadi. The last time he was detained for almost two months. The intelligence wanted to talk to him once more. I’m not sure you’ll find someone to tell you anything here.”

I then approached two men, one of whom seemed old enough to know all those who lived in the area in the last 40 years. When I asked if he knew Baghdadi, the man’s face changed, and he said with fear in his eyes while looking at his friend, “We don’t know him, he was one of few young students who lived here 15 years ago. Nobody knows him well. This is an old story that we prefer not to discuss.”

The last group of men I met were more forthcoming. A man in his late 70s told me he used to see him in the area but never spoke to him, while another man roughly the same age said, “He wasn’t the mosque’s imam, he was a tailor and he was a student too.” A third man, about 35 years old, said Baghdadi lived there while he was studying at the Iraqi University before the US invasion of Iraq. “He wasn’t alone, he had a family with him. The guy seemed very normal, and yes I do remember him very well,” the man told me.

The younger man waited until I left a group I had been standing with and then approached me, revealing that he knew Baghdadi very well. After introducing himself as Amjad, he said, “Sheikh Ibrahim [Baghdadi] was someone very normal, someone like you. He didn’t have any complexities in his life, and we used to play football here,” as he pointed to an empty piece of land next to the mosque. “He was obsessed with scoring goals; he would become nervous if he didn’t.” Amjad added, “When the US invaded Iraq he decided to take up arms and fight — he changed a lot after that.”

As Amjad finished speaking, one of the gentlemen I met earlier said, “Are you still asking about the same guy? We told you we don’t know anything about him. This is an old story and we have no intention to answer your questions.” It was obvious that my trip to Tobji was over, but my search wasn’t.

According to official documents, Baghdadi is married to two women who gave birth to his six children. His first wife, Asma Fawzi Mohammed al-Kubeisi, his first cousin, is the mother of Huzaifa, Omaima, Yaman, Hasan and Fatima. Israa Rajab Mahal al-Qaisi is his second wife and the mother of his youngest son, Ali. It is unknown whether Asma or Israa live with him, yet Abu Ahmad, who claims he has known Baghdadi since the 1990s and studied with him at the same university and was part of his close circle, suggested they reside within the territories that he controls. Abu Ahmad agreed to talk to me on two conditions: that he cover his face and we conduct the interview in my hotel room.

According to Abu Ahmad, the IS leader has three brothers: Shamsi, Jomaa and Ahmad. “There are serious differences between Sheikh Ibrahim and his brother Shamsi. On several occasions Shamsi objected openly to his brother’s choices, but this didn’t stop him from being detained by US and Iraqi forces many times,” Abu Ahmad said. “Jomaa was a Salafist from the beginning. He was an extremist even when Baghdadi was not yet part of that circle, causing many problems between them. But things are different now. Jomaa is one of his brother’s bodyguards and one of the closest aides to him. His third brother Ahmad caused Baghdadi some problems, and his reputation isn’t that good in regard to financial issues,” he added.

Shamsi is detained at one of the Iraqi intelligence detention facilities to the north of Baghdad and suffers from serious health problems. An official Iraqi security source ruled out the possibility of conducting an interview with him.

In regard to Baghdadi’s time at university, Abu Ahmad said, “Sheikh Ibrahim was a calm person. He used to take part in social activities, but started changing after he was introduced to Dr. Ismail al-Badri, who directed him toward a special path with the Muslim Brotherhood. He became a member of the jihadist Ikhwan [Brotherhood] and a sincere follower of Sayyid Qutb. He quit in 2000 after reaching the conclusion that they [Brotherhood] were people of words and not action.”

Hisham al-Hashimi, the author of “Inside Daesh” and an adviser to the Iraqi government on extremist groups, said Baghdadi became a Salafist in 2003. “He was influenced by Abu Mohammed al-Mufti al-Aali, the man who was seen at that time as the main ideologue of the jihadist groups in Iraq. Baghdadi along with other followers of Abu Mohammed — what was known as the Ahlu Sunna Waljama’

Then somewhere near Baghdad I met Abu Omar, a former IS member who was held three years at the Camp Bucca detention center that was managed by the US occupation forces in Iraq near the city of Umm Qasr. The camp was named after Ronald Bucca, an American firefighter who was killed during the 9/11 attacks in New York. “Camp Bucca was a great favor the United States did to the mujahedeen,” Abu Omar, who served his time at Camp Bucca for being a member of al-Qaeda, said. “They provided us with a secure atmosphere, a bed and food, and also allowed books giving us a great opportunity to feed our knowledge with the ideas of Abu Mohammed al-Maqdisi and the jihadist ideology. This was under the watchful eye of the American soldiers. New recruits were prepared so that when they were freed they were ticking time bombs.”

Baghdadi was arrested in 2004 while visiting an al-Qaeda-affiliated friend. At that point, the future IS leader wasn’t a member of the organization. He had just graduated with a master’s degree in Islamic studies from the Iraqi University in Baghdad, now known as the Islamic University of Iraq, and was preparing to start his doctoral degree. Hashimi said, “At Camp Bucca, Baghdadi absorbed the jihadist ideology and established himself among the big names. He met Haji Bakr, back then known as Samir al-Khlifawi, Abu Muhannad al-Suedawi, Abu Ahmed al-Alwani. These were officers in Saddam [Hussein]’s army, and despite their Baath origins they impressed him with their military knowledge. He also influenced them with his religious background — mainly his expertise in Quranic studies.”

Abu Omar, Baghdadi’s friend at Camp Bucca, filled in other details of Baghdadi’s daily life there: “I saw him playing football with other prisoners. I was amazed by his skills, and I understood later that he was given the name Maradona. This is the only thing I saw in him. I heard his speeches but he was nothing compared to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. His words lacked power,” he said.

During his years at Camp Bucca, Baghdadi built his contacts and established good ties inside Iraq’s al-Qaeda. As soon as he was released he became a member of the group, taking the name Abu Duaa as his alias. Baghdadi sought to continue his studies and acquired a doctoral degree in Sharia from the Islamic University in Baghdad. Outside prison, Baghdadi met Sheikh Fawzi al-Jobouri, one of the influential intellectuals within the ranks of Iraq’s al-Qaeda. Jobouri introduced him to the organization’s Minister of Information Muharib Abdul Latif al-Jubouri, who used his authority to help Baghdadi go to Syria and concentrate on his writings on condition that he would help in media issues whenever they needed him.

There was no obvious candidate within al-Qaeda in Iraq to succeed Zarqawi. He had possessed an unchallenged reputation and charisma within the organization’s ranks, and he had in fact posed as great a threat to the authority of Osama bin Laden as US President George W. Bush.

Zarqawi’s ideology differed from bin Laden and he resented pledging allegiance to bin Laden. Zarqawi’s priorities were different; he believed in focusing on the enemy nearby, not the one afar. This meant killing Muslim enemies, Shiites for instance, came before killing US soldiers. Because of the similarity of IS’ philosophy to Zarqawi’s beliefs, jihadists widely believe that Zarqawi is the real founding father of IS.

After Zarqawi’s death the creation of the Islamic State of Iraq, then affiliated with al-Qaeda, was also announced. Abu Omar al-Baghdadi was chosen as its first emir, while Abu Hamza al-Mohajer (known also as Abu Ayyub al-Masri) was his deputy and minister of war.

When he finished his studies, Baghdadi went back to Syria to take on more serious roles within al-Qaeda. He became the assistant of Abu Ghadiya, who was responsible for moving fighters through Syria to Iraq.

“Abu Ghadiya was said to have been killed by the US forces in a strike on the border between Syria and Iraq,” Hashimi said. “The truth is that he survived and was detained by the Americans. He was later handed over to the Iraqi authorities, but he succeeded in fleeing along with others on July 21, 2013, from Abu Ghraib prison.”

After the attack on Abu Ghadiya, Baghdadi returned to Baghdad, where he was introduced by Haji Samir, whom he met in prison, to the Islamic State of Iraq’s second-in-command, Abu Hamza al-Mohajer. Mohajer was impressed by Baghdadi and introduced him to the group’s emir, Abu Omar. It was clear that Baghdadi had sponsors inside the Islamic State of Iraq who helped him to quickly climb the ranks. “His relation with Abu Omar wasn’t direct at the beginning, yet Mohajer recommended him for several roles,” Hashimi said. “He was later appointed as member of the powerful Shura Council.”

Iraqi intelligence believes that Baghdadi was later promoted to be a member of the coordination committee. “Members of al-Qaeda call it the blessed coordination committee. It’s responsible for coordinating between the emir of the organization and governors of the states,” Maj. Bakr, the intelligence officer, said “He was one of three men and became the most prominent and trusted one among them. Abu Omar al-Baghdadi gave this committee high authority.”

During this period, Baghdadi began to be noticed. The higher he climbed up the al-Qaeda organizational ladder, the higher he was ranked on Iraq’s most-wanted list. It was not until April 18, 2010, that he became a priority to be captured.

On that date, Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Ayyub al-Masri were both killed in a US-Iraqi joint operation. Al-Qaeda in Iraq had lost its leader and his deputy, and there was a dire need to choose a successor. Al-Monitor found that Haji Bakr backed Sheikh Ibrahim to be the next emir of al-Qaeda in Iraq. But bin Laden wanted a different man — Haji Iman — to be the successor. This made Haji Bakr’s task difficult; he had to convince the key players that the man he supported was the best choice. Eventually, he succeeded, and nine members of the Shura Council agreed to vote for Sheikh Ibrahim.

Former IS member Abu Omar said one of the main reasons for Baghdadi’s selection was that he was descended from the Quraysh, the same tribe of the Prophet Muhammad, one of the conditions for being selected as caliph. “This was very important to those planning the future strategy of the group, those who wanted to fulfill Zarqawi’s dreams in subsequently announcing the caliphate,” Abu Omar said. “There was a great challenge to face after the Sharia Council abstained from accepting him. He [Baghdadi] wasn’t up to it, I heard many of his speeches, he lacked the charisma, he’s not to be compared with Zarqawi.”

Sheikh Ibrahim then chose the name Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as an alias — an odd choice for someone hailing from Samarra. “It’s like saying that Baghdad will always be their target,” Abu Omar said. “The final battle will be in Baghdad. Baghdadi wants to revive the glory of the Abbasid Caliphate, so this is also a message to the enemy that Baghdad is ours.”

Baghdadi’s main mandate was to revive the Islamic State of Iraq. He started by gathering members he thought were capable of helping him achieve his goal. Within a few months, the Arab Spring ignited and the revolution in Syria began. It was the best opportunity for the group to spread in a fertile environment.

Months later, developments further cleared the field for Baghdadi. Bin Laden was killed and the less charismatic Ayman al-Zawahri succeeded him. Taking advantage of the leadership vacuum, Baghdadi sent two of his aides to Syria to expand his state. These aides, Abu Mohammad al-Golani and Mullah Fawzi al-Dulaimi, formed Jabhat al-Nusra.

The new group started gaining ground within months and Baghdadi decided it was time to declare a state under his rule in both countries under the name of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Golani, however, refused to go along with Baghdadi’s decision, as did Zawahri. These were hard times for Baghdadi’s organization as it stood on the verge of its first serious defection.

“Abu Mohammad al-Golani was one of Baghdadi’s soldiers,” Abdel Bari Atwan, a veteran Arab journalist who met bin Laden and wrote a book on ISIS, said. “He was sent to establish a branch for the Islamic State in Syria. Baghdadi wanted to expand through Golani, but the latter decided to instead look to their leader [Zawahri]. He [Golani] wanted to be a branch for the main al-Qaeda, he wanted to be an emir in the same way as Baghdadi. He also wanted it to represent the Syrians only.”

Golani’s decision intimidated Baghdadi, who decided to take revenge by going himself to Syria. “Golani’s move was a punch in the face to Baghdadi; it was a stab in the back,” Abu Omar said. “Baghdadi gave him everything; men, money and contacts. Yet, Golani saw himself as a possible leader with direct links to Khorasan [al-Qaeda’s central command]. He thought it was time to make a great leap.” A serious crack appeared within al-Qaeda in Syria: Baghdadi and Golani were at war with each other. Soon ISIS began taking control of areas that were held by Jabhat al-Nusra, and Raqqa was the first Syrian province to fall completely into the hands of ISIS. It was obvious Baghdadi’s men had the upper hand in the fight, and in June 2014, ISIS entered Mosul in Iraq and delivered the decisive blow in the battle for supremacy, starting a new era.

Baghdadi declared the caliphate and pronounced himself as the new caliph. “Four men declared him caliph — Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, Abu Ibrahim al-Masry, Turki al-Binali and Abu Suleiman al-Otaibi — before his defection,” Hashimi said. “They convinced him to take this step fearing that Zawahri might precede them; such a declaration attracts new recruits and donations.” The move put to rest the competition.

The journey was complete, and Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai — the local imam, academic, US-held prisoner and al-Qaeda officer — had become Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.