Hezbollah’s ambitions are spreading far beyond its Lebanon home as the movement appears increasingly bent on taking on radical Islamist foes across the Middle East. It has sent thousands of its fighters into Syria and senior military advisers to Iraq, helped rebels rise to power in Yemen and threatened Bahrain over its alleged abuse of Shiites there.

But the regional aspirations also are taking a heavy toll and threatening to undermine Hezbollah’s support at home. The group has suffered significant casualties, there is talk of becoming overstretched, and judging by the events of recent days, even a vague sense that the appetite for fighting the Israelis is waning.

In the recent confrontation, Israel struck first, purportedly destroying a Hezbollah unit near the front line of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. Among the seven dead on January 18 were an Iranian general, a top Hezbollah commander and the son of another former commander in chief. A heavy Hezbollah retaliation appeared inevitable.

Yet when it came last Wednesday, Hezbollah’s revenge was relatively modest: two Israeli soldiers dead, seven wounded. The choice of location — an occupied piece of land excluded from a UN resolution that ended the 2006 war between Hezbollah and the Israelis — suggested to some that Hezbollah’s mind remains focused on more distant fronts.

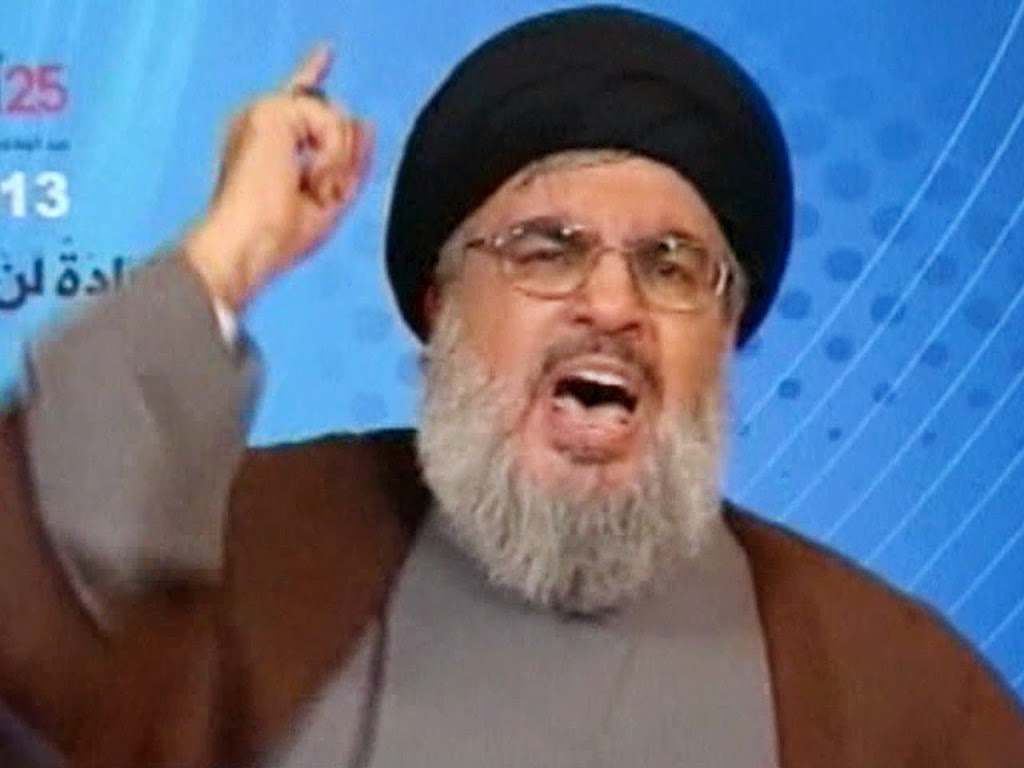

The Hezbollah leader, Shaikh Hassan Nasrallah, seemed to allude to criticism that Hezbollah’s taste for foreign campaigns is weakening its appetite for fighting the Israelis. In his speech on Friday, Nasrallah said Israel had incorrectly thought that “Hezbollah is busy, confused, weak and drained. … The resistance is in full health, readiness, awareness, professionalism and courage.”

It is part of a complex equation for Hezbollah: On the one hand, many Lebanese resent the group for embroiling their vulnerable country in ruinous wars with the Israelis. But on the other, all shades of Muslim opinion see the Israeli regime as a common enemy that Hezbollah forced, in 2000, to end an 18-year occupation in south Lebanon. In that sense even Sunnis, who along with Christians and Shiites make a third of the country’s population each, could see Hezbollah as a protector.

But that was then. Today, many increasingly look to powers as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt as their true backers.

“Increasingly, Hezbollah’s leadership perceives itself as a Shiite Arab regional actor, placing its commitment to the Palestinian cause on par with its mission as a defender of Shiite political and religious rights in the Arab region,” said Randa Slim, a director at the Washington-based Middle East Institute. “The consequence for Lebanon is that at some point the Shiite underpinnings of Hezbollah’s regional role will clash with the interests and demands of its non-Shiite, mainly Sunni compatriots.”

Hezbollah has room to grow as a leading defender of Shiites. But when Nasrallah has tried to make aggressive political proclamations, the results sometimes have backfired.

On January 9, Nasrallah harshly criticised Bahrain over its crackdown on a Shiite-led uprising and its arrest of a leading Shiite cleric, Ali Salman. He compared Bahrain to his archenemy Israel, saying it was naturalising foreigners to make the Gulf island increasingly less Shiite.

Nasrallah then issued a veiled threat to Bahrain, although he said protests should remain peaceful. “Weapons can be sent to the most secure countries. Fighters and gunmen can enter and small groups can sabotage a country,” he said.

Hostile reaction swept the Arab world and Lebanon, where even some Shiites complained that threatening Bahrain could spur Gulf nations to expel Lebanese Shiites from their soil. The six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council called Nasrallah’s comments “hostile and irresponsible.” The 22-nation Arab League accused him of meddling in Bahrain.

Hezbollah’s largest and most visible commitment is in Syria, where thousands of Hezbollah members are fighting alongside President Bashar Al Assad’s forces against rebels.

When Hezbollah first sent fighters to Syria in late 2012, Nasrallah said their role was to defend Shiite holy shrines near the capital, Damascus. Their role expanded to the defence of predominantly Shiite Lebanese residents of Syrian villages. The group now says its main reason to be in Syria is to prevent radical Islamists from moving into Lebanon.

Hardly a week passes without Hezbollah’s Al Manar TV airing funerals for fighters slain in Syria. Last year, a Hezbollah commander, Ebrahim Mohammad Al Haj, was killed while on a “mission” in Iraq.

Hezbollah positions in Lebanon also face repeated attacks mostly by an Al Qaida-linked group, Al Nusra Front, based on the Syrian side of the border. Their wave of bombings since late 2013 have killed and wounded scores of people, and obliged Hezbollah to employ stiff security countermeasures, including the deployment of plainclothes Hezbollah members around the clock in Shiite business districts south of Beirut.

In Yemen, security officials say Hezbollah, which has long had a presence, has dispatched increasing number of cadres to the impoverished country since Al Houthis took over the capital, Sana’a, in September and later the airport.

The officials said before the takeover of the capital, Hezbollah had military and security advisers based in the Al Houthi’s stronghold of Saada province near the Saudi border, where the group’s leader, Abdul Malek Al Houthi, is based.

Analyst Rami Khouri recently wrote in Lebanon’s Daily Star newspaper that all the adventurism has come at a political price.

“Hezbollah was widely acclaimed in much of Lebanon and the region for leading the battle to liberate south Lebanon from Israeli occupation,” he wrote. “Today, the very polarised Lebanese see the party either as the nation’s saviour and protector — or as a dangerous Iranian Trojan horse.”Source: gulfnews