Egypt may need to consider securing its borders with Libya to prevent the infiltration of armed groups.

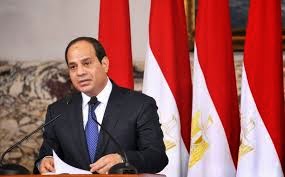

Since his rise into the political spotlight about 18 months ago, Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has presented himself domestically and abroad as a leader in the fight against political religious groups in the region.

The slaughter of 21 Coptic Egyptian workers by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in Libya, and the retaliatory air strikes launched by Egypt’s military, have expanded Sisi’s regional war against such groups. The developments come just weeks after Egypt declared al-Qassam Brigades, the armed wing of the Palestinian faction Hamas, a “terrorist group”.

Sisi frequently fails to differentiate between groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood and more violent and hardline organisations, such as al-Qaeda and ISIL.

Domestically, the Egyptian president launched a massive crackdown against the Brotherhood, Egypt’s largest political opposition group, declaring it a “terrorist” organisation, arresting its leaders and banning its political party. A widening military campaign against ISIL affiliates in Sinai has killed hundreds of people, including civilians.

Egyptian media and state officials have often blamed Hamas for attacks on Egypt’s security forces in Sinai. Egypt has also declared its support for Libya’s internationally recognised government in Tobruk, which has been engaged in a months-long armed struggle against a parallel government in Tripoli, which is supported by armed groups and the General National Congress.

Egypt, with backing from the United Arab Emirates, has often been accused of providing military support to the forces of Khalifa Haftar fighting alongside the Tobruk government – allegations Egypt has denied.

Egypt’s air strikes against ISIL targets may be seen as a new chapter in Sisi’s regional confrontations with hardline groups. In a speech to the nation on Sunday night, Sisi told Egyptians that his country “reserves the right to respond by the appropriate measures and at the appropriate time in retribution against those killers”.

It remains to be seen how far Egypt’s armed campaign will go against ISIL targets in Libya, but internationally, the air strikes could represent an opportunity for Sisi’s regime, giving it a larger role in the growing international coalition against ISIL and its regional affiliates.

In December, the United States delivered 10 Apache helicopters to Egypt after holding back military aid since the military coup led by Sisi ousting Egypt’s democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi. The delivery was primarily justified by Egypt’s need to fight ISIL in Sinai. Egypt was also expected on Monday to sign a $5.9bn deal to buy 24 Rafale jet fighters from France.

The air strikes could also help Sisi gain domestic support at a crucial time, with his regime facing growing criticism by supporters and foes alike over his stalled political agenda and unprecedented human rights violations.

In addition, at the end of January, more than 40 members of Egypt’s security forces were killed in a coordinated attack in North Sinai, shaking Egypt’s trust in the abilities of its military to keep control of the strategic peninsula.

Sisi could also use his expanding war against ISIL to further suppress any demands for political reforms. A parliamentary election scheduled for March is effectively being boycotted by the majority of political forces that led the January 25 revolution.

Despite such opportunities, Egypt’s intervention in Libya also presents Sisi with new challenges. It shows the growing threat posed by ISIL to Egypt as the group expands in Sinai in the east and Libya to the west.

Air strikes have so far been unable to defeat ISIL throughout the region, and they have also caused civilian casualties, further deepening tensions. Egypt may need to consider securing its borders with Libya, which have long been scarcely inhabited, to prevent the infiltration of armed groups.

At the same time, the Egyptian military intervention could undermine dialogue opportunities between the two main political groups in Libya, the Tobruk and Tripoli governments.

A UN-sponsored dialogue process finally succeeded in bringing the two sides together last week in Ghadames, but they have yet to talk directly to each other. The military intervention by Egypt, which favours the Tobruk government, could ultimately upset the balance between the parties and risk deepening the conflict.

Source: Al Jazeera