Armed with sledgehammers, chisels and a video camera, ISIS militants took their propaganda campaign to Mosul museum last month, destroying statues and artifacts, dating back to the ancient Assyrian and Akkadian empires, and posting the results online and in slow motion.

The terror group’s impetuous destruction of statues and artefacts in Iraq’s second city, which it has controlled since its march across the Sunni-majority northern regions of Iraq last summer, has caused dismay within the archaeological community.

While many believe that the group attacks or loot antiquities for mere shock value or financial gain, ISIS holds an intolerance towards items that are deemed jahili (pre-Islamic) and antiquities that depict humans, such as Roman statues or mosaics, according to Dr Hafed Walda, the pending deputy ambassador to the permanent Libyan delegation at Unesco.

“There are threats to destroy statues, specifically from museums, because for them any antiquity that represents a human being should be destroyed,” he says. “Their eyes are on big museums which have fine collections of Greek and Roman sculptures. This is where they are focusing at the moment.”

Notable archaeologists and experts have raised their concerns about the threat presented by the wanton vandalism of cultural treasures that is coming to define the group and its growth in other countries of cultural importance, particularly the increasingly lawless coastline of Libya, where a number of historic Roman sites are situated.

Because of ISIS’s “criminal vandalism” in Mosul, Paul Bennett, the head of mission at the UK-based Society for Libyan Studies, wrote to Unesco’s director-general Irina Bokova, of his “extreme concerns for the antiquities of Libya” because of the very real threat of similar attacks by the terror group in the country.

Libya’s descent into chaos since the fall of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 has given rise to looting of cultural treasures and the damaging of ancient sites, such as the Karamanli Mosque in Tripoli (which gunmen stripped of its ceramic tiles) and attacks against holy Sufi shrines in the city of Zlitan, both in 2012. However, the rising influence of ISIS in the country, particularly along the Mediterranean coastline, has brought the group closer to sites of historical significance, outside of its self-proclaimed caliphate in Iraq and Syria, than ever before.

The group now controls the north-eastern coastal town of Derna, and holds a presence in a number of vital towns and cities, including Tripoli, where it claimed responsibility for an attack on the Corinthia hotel in January that killed nine people; Benghazi, where it is battling the Operation Dignity forces of former Libyan general Khalifa Haftar alongside other jihadi factions, such as Ansar al-Sharia; and Sirte, where it has captured the main university and is believed to have carried out the execution of 21 Egyptian Coptic Christians on the shores of the Mediterranean last month.

Lining the coast are a number of irreplaceable Unesco World Heritage Sites that are now endangered by the growing strength of ISIS. One of the sites, Leptis Magna, is situated 130km east of the capital, Tripoli, and 100km west of the country’s third city, Misrata, which Libyan ISIS militants have proclaimed to be one of the group’s prime targets. Here, the great Roman Emperor Septimius Severus built a forum, an improved harbour and a great basilica. There is a museum attached to the site which, like Mosul museum, houses invaluable statues and would be a likely target for extremists.

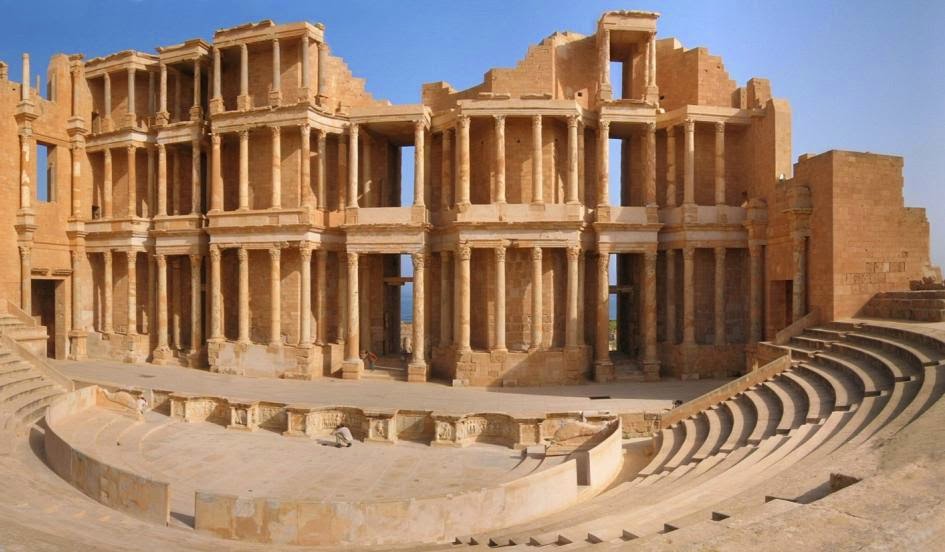

Also under threat from Libyan and foreign jihadis are the western coastal town of Sabratha and the archaeological site of Cyrene, in the eastern town of Shahat, which had acted as a local Roman capital. Sabratha, which hosts two important museums which store coins and mosaics from the Byzantine era and statues from the Roman period, is currently under control of Islamist Libya Dawn forces, who support the General National Congress (GNC), a rival to the internationally recognised government in Tobruk.

Cyrene hosts “one of the most impressive complexes in the entire world”, according to the cultural agency, but now finds itself sandwiched between the ISIS-controlled town of Derna and the city of Benghazi, where an ISIS cell is battling for control.

Mohamed Eljarh, Libyan analyst and non-resident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Centre for the Middle East, warns that, while extremists have routinely targeted Libya’s heritage since 2011, these “significant ancient sites” are at “high risk of being targeted by the group as part of its propaganda war”. “Given that a huge part of ISIS’s expansion strategy is their media exposure and propaganda, I fear that significant ancient sites such as the Roman ruins in Sabratha and Leptis Magna are the two sites with the highest risk of being targeted by ISIS militants. The group now has a presence in Sirte and Tripoli. This puts them in very close proximity to these two important sites of Libyan heritage.”

Issandr El Amrani, director for International Crisis Group’s North Africa Programme, is pessimistic about the prospects of securing the “completely unprotected” sites. “ISIS is driven to a large extent by doing things that have a propaganda value more than a practical military value so, yes, they could be tempted to [attack the sites], to create the narrative that they are fighting anything that is jahili (pre-Islamic),” says Amrani.

As the North African country continues its slide into chaos, becoming a magnet for foreign fighters, and an embryonic extension of ISIS’s caliphate, there seems to be little hope for Libya’s cultural legacy. UN-brokered talks between the two rival factions in the country have collapsed and the international community continues to refuse a lifting of a UN arms embargo on the country in order to allow the recognised government to tackle jihadi groups.

In the aftermath of the Mosul attack, Unesco director general Irina Bokova told a press conference that the UN’s cultural body “does not have an army” and “there is not much we can do” to prevent the looting and damage of antiquities in war-torn areas. But, for Libya, Dr Walda disagrees with Bokova, proposing tough security measures as a solution to protect his country’s rich history. “We have to fortify the museums,” he says.